|

|

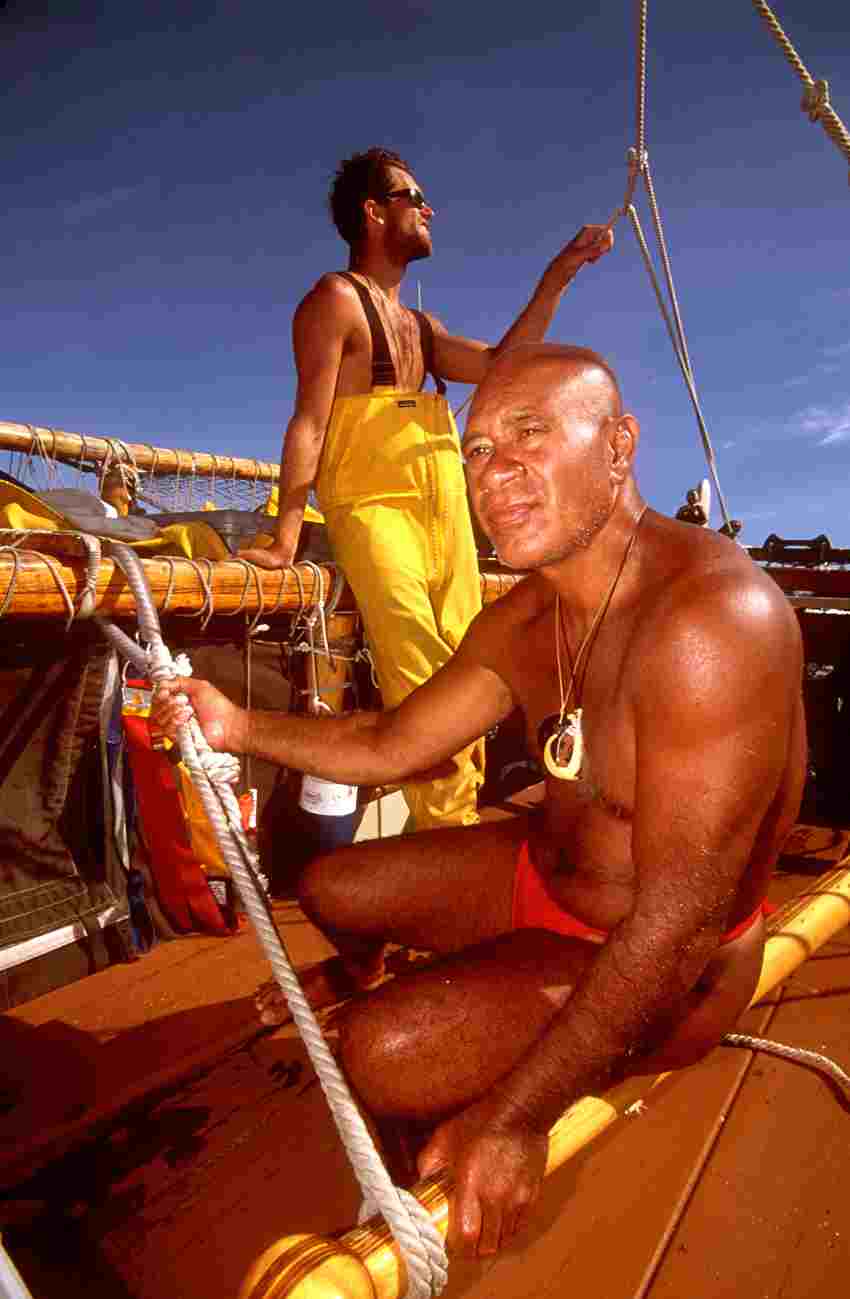

Navigator Bruce Blankenfeld seeks clues of land ahead

Sea Paths Martha's Vineyard Magazine

Voyaging aboard an ancient Polynesian canoe reveals a way of living in balance with the natural world. By Sam Low

When mainlanders confront the ocean they perceive an obstacle. Islanders see a path. To look out over ocean paths, Vineyarders built widows' walks atop their houses. From these high perches they saw as far as Australia and England . They saw the Sandwich Islands and the coast of California . Islanders perceive the world differently than mainlanders because they are connected to places in it by the sea. This story is about very ancient sea paths - about my Polynesian family who inhabited from time immemorial islands sprinkled like tiny emeralds in the Pacific Ocean .

In 1980, I began to explore my Polynesian roots by making a PBS documentary called The Navigators – Pathfinders of the Pacific. My research revealed that the first Polynesians reached Fiji by sailing sea paths from a homeland somewhere in Southeast Asia at about the time the walls of Troy were falling to the Greeks. When Christ was born, they set out against prevailing winds and currents to Tahiti and New Zealand and then on to Hawaii and Easter Island . Thor Heyerdahl got it wrong. Polynesia was not settled by hapless drifters from the mainland of South America but by sailors who navigated by the stars in powerful double-hulled ocean-going canoes. Polynesia was settled by islanders.

In 1999, I was invited aboard Hokule'a - a replica of an ancient Hawaiian canoe - to retrace a traditional voyaging route, the most difficult of all, from the island of Mangareva in the South pacific to a remote speck of land – Easter Island - or, as it's known by Polynesians - Rapa Nui . The voyage would be the ultimate test of ancient techniques of non-instrument navigation. Rapa Nui is only thirteen miles wide and 1,600 feet high. After a passage of more than 1500 miles, we must sail within thirty miles of the island to spot it. A navigational error of only a half a degree of latitude will cause us to sail past. If that happened, the next landfall is South America - 2,000 miles away.

Our navigator, Nainoa Thompson, will guide the canoe as ancient Polynesians once did. Without instruments or charts, he relies instead on an intimate familiarity with nature. For a compass he steers by the rising and setting points of stars. By Mintaka, for example, a bright star in Orion that rises due east and sets in the west. Or by the North Star that sits nearly stationary in the sky, defining the north celestial pole; or the two “pointers” in the Southern Cross - Gacrux and Acrux - which always point south. To guide the canoe at night, Nainoa has memorized the paths of over 130 stars. During the day, he steers by the sun and by steady ocean swells stirred by nearly constant trade winds. To find his latitude he observes the meridian crossing (the highest point of rising) of various stars – but it takes a trained eye. A mistake of a single degree in estimating a star's altitude is equivalent to 60 miles of error on the ocean. Longitude, a vessel's position on the planet in an east-west direction, is another matter. Without a chronometer, Nainoa uses dead reckoning. He estimates daily the course he sailed and the distance made good. And he does this on some voyages for more than a month.

“Navigation is about understanding and watching nature,” Nainoa told me before we set out. “Everything you need to guide you is in the ocean, but you need to be skilled enough to see it. For me to learn all the faces of the ocean, to sense the subtle cues, the slight differences in ocean swells, in the colors of the ocean, the shapes of the clouds and the winds, and to unlock these cues and glean their information will take many years more (he already has spent 25 years in this effort). Initially, I used geometry and analytic mathematics to help in my quest to navigate the ancient way. But as my ocean time has grown, I have internalized this knowledge, and my need for mathematics has diminished. I come closer and closer to navigating the way the ancients did.”

I remember my father. He grew up in Hawaii at a time when Hawaiian culture was dying. A time when native Hawaiians had been nearly eradicated by disease and the language was no longer taught, was in fact forbidden in Hawaiian schools. My father's parents, like so many others, considered it useless to practice an ancient culture. Better to learn the ways of the haole – the white man – and to progress in a new world. The values of a distinct island way of life faded. Then a remarkable thing happened. Hokule'a was launched in 1975 and she rapidly became a powerful symbol of cultural revival.

“Voyaging canoes were the spaceships of our ancestors,” as one of my Hawaiian friends once put it, “they were the highest achievement of our technology. So when Hokule'a sails she kindles our pride. She taught us that as a people we can do anything we set our minds to.” “That's why we sail,” Nainoa says, “so our children can grow up and be proud of who they are. We are healing our souls by reconnecting to our ancestors. As we voyage, we are creating new stories within the tradition of the old stories, we are literally creating a new culture out of the old.”

The classic art of Hawaiian hula is widely practiced Hokule'a has galvanized an entire generation of Hawaiians who are now learning and practicing their ancient culture – reviving art, dance, language, spirituality and curing practices. Recently, the first class of high school children graduated, having spent their entire 12 years in a language immersion program speaking only Hawaiian.

On October 2 nd , our 12 th day at sea - the wind slackens. We proceed toward Rapa Nui over an ocean that undulates toward the stark horizon like a giant satin sheet. One of my watch mates, beginning his turn at the steering sweep, steps up behind the helmsman. He studies how the big southeastern swell moves under the canoe, how the helmsman steers by keeping it off the starboard bow. Then he taps him on the shoulder and steps into his place, accepting the smooth knob of the paddle and the responsibility that goes with it. Aboard the canoe there are many silent rituals like this one - expressive of shared trust.

"Voyaging aboard Hokule'a has taught me a lot about the word love," says Ben Tamura, the canoe's doctor, "it's a word that is often misunderstood. People think you can only have real love between a man and a woman. That's not what I'm talking about. Voyaging has given me a feeling of love in an altruistic sense that I can't put into words easily. It's different from how the media or even classic literature portrays it. It's like the word "aloha." How can you define that? There are so many different meanings."

"When I was younger," says Mike Tong, who is a veteran of every one of Hokule'a's dozen or so voyages, "sailing was an adventure - a test - I just wanted to go. I didn't think about much else. But now I think about a lot of other things before I go. I think about my family and being sure they are comfortable with my sailing. I think about my larger ohana - my community - and that all of us on the canoe represent our islands and our people. I think about what values the voyage has for all of us - both those aboard the canoe and those at home-the values of aloha, of team work, self discipline, and of always having a larger vision of why we sail which will carry us through the hardships ahead.”

On a training sail a few years ago, Hawaiian astronaut Lacey Veach was invited aboard. “Your crew is amazing,” he later told Nainoa. “There is no shouting, all orders are given calmly and followed precisely. I've never seen such harmony.”

“The Hawaiian concept of malama – of ‘taking care,'" explains Mike Tongg, "may have evolved from our heritage of long distance voyaging. Our ancestors learned they had to take care of the canoe and that if they did, the canoe would take care of them; they also learned they had to take care of each other." Sailing under an immense sky dome in an empty sea has had a transforming effect. In mid ocean, a thousand miles from landfall, we are surrounded by a horizon populated only by clouds and stars. We begin to feel totally dependent on the natural world around us. “When you voyage, you become much more attuned to nature,” Nainoa says. “You begin to see the canoe as nothing more than a tiny island surrounded by the sea. We have everything aboard the canoe that we need to survive as long as we marshal those resources well. We have learned to do that. Now we have to look at our islands, and eventually the planet, in the same way. We need to learn to be good stewards."

Ancient Polynesians fashioned canoes like Hokule'a with stone tools. They used koa wood for the hulls, breadfruit sap and coconut husks for caulking, and coconut fiber rope for lashings. With materials from the land they fashioned a vessel to blend with the sea.

“When our ancestors went to the mountains to cut down trees they did not think they were taking the tree's life,” crewmember Bruce Blankenfeld once told me. “They were just altering its essence, taking it from the forest and putting it into the sea, and in Hawaii the sea and the land are tied together. Everything in the sea has a counterpart on the land because on an island the land and the sea rely on each other for life.”

Polynesian islanders recognized the inherent “oneness” of their natural world because islands are fragile places where the interaction of man and nature is clearly seen. When they cut the trees in their valleys they must have noticed the effect of pollution from runoff on their reefs. This may explain why ancient Polynesians constantly balanced the resources of land and sea in their rituals. Some anthropologists call it “dualism” and believe they have discovered in such ‘primitive' societies a yin and yang universal in human thought. But I think it's simpler than that. If ritual reinforces ways of living essential for survival then it is no mystery why Polynesian islanders recognized the aholehole fish as ritually equivalent to a species of taro plant. Today, we are so distanced from this basic understanding of connectedness that we use a relatively new word to express it – ecology.

“When we sail we find ourselves surrounded by an empty ocean which forces us to turn inward and consider how to take care of ourselves, each other, our canoe,” says Nainoa. “Learning to survive on long voyages also forces us to consider how to survive on the islands we live on, it's a microcosm for learning to survive everywhere. In Hawaii we are surrounded by the world's largest ocean, but Earth itself is also a kind of island, surrounded by an ocean of space. In the end, every single one of us - no matter what our ethnic background or nationality - is native to this planet. As the native community of Earth we should all aspire to live in pono - in balance - between all people, all living things and the resources of our planet.”

By the time Nainoa had begun this voyage, he had already traveled more than 85,000 miles aboard Hokule'a. He had focussed 25 years of his life on the canoe. By his calculation he had served with 130 different crew members and he had learned much not just about navigation, but about leadership and about planning and executing the complex logistics of supplying a ship at sea on voyages that have lasted as long as two years. Voyaging, not just navigation, had become his life and he coined a new word to cover the complexities of what he had learned. Wayfinding. He says that wayfinding is "a way of organizing the world." He also says that it's "a way of leading," "of finding a vision," "a set of values," and, in general, "a model for living my life."

The winds blow strong from the northeast on our 17 th day at sea and on into the 18 th. Hokule'a responds by speeding east-southeast - slicing through the waves, producing long tendrils of spray from her bow. Nainoa knows we are approaching Rapa Nui , but clouds have obscured the sky for three days, so he's navigating by dead reckoning from his last latitude fix. Lookouts are posted.

Near dawn, crewmember Max Yarawamai spots two holes in the clouds ahead low on the horizon. Born and raised on the low Micronesian atoll of Ulithi, Max's ability to see islands at great distance is legend aboard Hokule'a.

"I looked carefully at the two holes on the horizon," Max explained later, "checking first the one on the starboard side. I saw nothing there so I switched to the hole on the port. I saw a hard flat surface there and I watched it carefully. Was it an island? The shape didn't change! It was an island all right. We had found the dot in the ocean."

Why did the Polynesians set out on such long and dangerous voyages? Some scholars resort to explanations of overcrowding on tiny islands, of internecine warfare, or banishment - but I think the real answer is that they voyaged because they were islanders. They shared an urge to know more about their world – a desire to explore. It was a way of life that had evolved over thousands of years of fanning out into the setting sun and always discovering land there. The canoe and sailing the sea paths came to embody all that they aspired to. The question is not ‘why did they voyage,' but rather ‘why not?'

Polynesian canoe - art by Herb Kane

|

Sam Low.com home | Biography | Library | Gallery | Screening Room | Forbears | Notebook | Contact Sam

Site, text, and images Copyright © 2002 Sam Low. All rights reserved. Any or all content may not be used without Sam's permission.

On

September 21 st , we jump off from Mangareva and set our course almost

due east. Instead of a constant slog into the normal southeast trades,

we encounter miracle winds – strong from the north, west and south.

We run under cloudy skies at 6, sometimes 7 knots. We experience squalls

and heavy seas, but Hokule'a rises easily over the swells, channeling

tons of water cleanly between her twin hulls. She seems alive - responding

to the forces of nature as she was designed to, a testament to the genius

of our ancestors. On our 10 th day at sea, the sky clears and presents

millions of stars. Jupiter rises ahead – just where the sail blocks

the sky – almost due east. When it's my turn to steer, I allow the planet

to appear briefly, then push Hokule'a's massive steering paddle down,

causing the canoe to turn up into the wind until Jupiter begins to swing

behind the sail. Then I drop the blade, Hokule'a turns down – Jupiter

reappears. The polished ball of the steering paddle curves into my hand

and the canoe speaks to me with pressure against my open palm. The stars

cascade overhead while the planet rolls toward daylight. This night,

thick with stars, timeless, begins to spin a web of memories.

On

September 21 st , we jump off from Mangareva and set our course almost

due east. Instead of a constant slog into the normal southeast trades,

we encounter miracle winds – strong from the north, west and south.

We run under cloudy skies at 6, sometimes 7 knots. We experience squalls

and heavy seas, but Hokule'a rises easily over the swells, channeling

tons of water cleanly between her twin hulls. She seems alive - responding

to the forces of nature as she was designed to, a testament to the genius

of our ancestors. On our 10 th day at sea, the sky clears and presents

millions of stars. Jupiter rises ahead – just where the sail blocks

the sky – almost due east. When it's my turn to steer, I allow the planet

to appear briefly, then push Hokule'a's massive steering paddle down,

causing the canoe to turn up into the wind until Jupiter begins to swing

behind the sail. Then I drop the blade, Hokule'a turns down – Jupiter

reappears. The polished ball of the steering paddle curves into my hand

and the canoe speaks to me with pressure against my open palm. The stars

cascade overhead while the planet rolls toward daylight. This night,

thick with stars, timeless, begins to spin a web of memories.

Our

community is tiny – thirteen in all. Our average age is 47. We are in

decent shape, but with a few exceptions, none of us are specimens. We

are what Nainoa likes to call “professionals” in the broad sense of

the word – seasoned by life, dedicated to our work and families. Our

composition is not an accident. “I chose the crew carefully,” Nainoa

says. “I wanted people who shared common values, who would get along

on a difficult voyage, who would support each other no matter what.”

Our

community is tiny – thirteen in all. Our average age is 47. We are in

decent shape, but with a few exceptions, none of us are specimens. We

are what Nainoa likes to call “professionals” in the broad sense of

the word – seasoned by life, dedicated to our work and families. Our

composition is not an accident. “I chose the crew carefully,” Nainoa

says. “I wanted people who shared common values, who would get along

on a difficult voyage, who would support each other no matter what.”

"Our

ancestors began all of their voyages with a vision," he once explained.

"They could see another island over the horizon and they set out

to find these islands for a thousand years, eventually moving from one

island stepping stone to another across a space that is larger than

all of the states of Europe

combined. To accomplish this great feat they needed the ability to plan

intentional voyages of discovery, the discipline to train physically

and mentally, the courage to take risks and a deep sense of aloha to

bind the crew together during the voyage. These are Hawaiian values

– vision, planning, discipline, courage and aloha - but they are also

universal values. They worked in the past and they will work today.

After a while, if you apply all those values, it becomes a way of life."

"Our

ancestors began all of their voyages with a vision," he once explained.

"They could see another island over the horizon and they set out

to find these islands for a thousand years, eventually moving from one

island stepping stone to another across a space that is larger than

all of the states of Europe

combined. To accomplish this great feat they needed the ability to plan

intentional voyages of discovery, the discipline to train physically

and mentally, the courage to take risks and a deep sense of aloha to

bind the crew together during the voyage. These are Hawaiian values

– vision, planning, discipline, courage and aloha - but they are also

universal values. They worked in the past and they will work today.

After a while, if you apply all those values, it becomes a way of life."