|

|

The Challenge By 1995, Hokule'a had sailed almost eighty five thousand miles since her launching twenty years earlier. She had voyaged between Hawaii and Tahiti five times, between Tahiti and New Zealand twice, and she had visited the Marquesas, Tuamotus, Cooks, the Australs and Samoa - all the corners of an immense tract of ocean that geographers call the Polynesian Triangle - except one, the eastern corner, which is occupied by a tiny island in an immense and empty sea. Europeans know it as Easter Island, but throughout Polynesia it is called Rapa Nui. "We have never sailed to Rapa Nui before not because we didn't want to," Nainoa once said of the voyage, "but because we didn't think we could do it." In 1999, he decided to try. The trip Nainoa envisioned would be made in five segments - Hawaii to the Marquesas, the Marquesas to Mangareva, then on to Rapa Nui and back to Hawaii with a stop in Tahiti. Every one of those passages would be difficult - but none more than the third segment - the one to Rapa Nui. Setting out for Rapa Nui from Mangareva, Nainoa expected to tack into almost constant headwinds, extending the distance Hokule'a must travel from 1500 seagull flying miles to more than 4000 zigzagging ones. Every mile would be cold and wet. The constant head winds would try the crew's endurance. Adding to the difficulty was the fact that Rapa Nui is a tiny target, only 14 miles wide. Navigating without instruments or charts, Nainoa and his crew would have to find the island by using only a world of natural signs - stars, waves and flight of birds. As an example of the exactitude required, an error of only a degree of latitude, calculated by the flickering light of a distant star, would cause Hokule'a to sail past the island. The next landfall would be South America - two thousand miles away. The voyage, as Nainoa envisioned it, would be the ultimate test of the skills of ancient navigators and explorers, it would be a journey deep into the past - into the heart and soul of a people many consider the world's greatest ocean explorers, and it would be an opportunity to reunite the people of Rapa Nui, long a colony of distant Chile, with their Polynesian family to the west. "We do not explore because it's easy," Nainoa told his crew as they prepared for the voyage, "we explore because it's a great challenge. We go to Rapa Nui in great humility and respect for our ancestors, we go to rekindle the pride and dignity of our people and to reunite our ancient seafaring family." The canoe set off on June 15th from Hilo and traveled to the Marquesas where she made stops at Nuku Hiva, Ua Pou, Ua Huka, Tahuata, Fatu Hiva, and Hiva Oa - each island seemingly more beautiful than the last. Going ashore, the crew saw ancient temples, wild horses, deep crenellated valleys rich with vegetation, and mountains arching into the sky - landscapes so perfect in their effect they appeared almost Hollywood stage sets. Here, they experienced moments of deep human connection. Enroute to Mangareva, Hokule'a anchored in Bounty Bay, Pitcairn Island, an isolated land of steep chocolate roads, fields rich with fruit and vegetables, and peopled by a large extended family - the descendants of the Bounty Mutineers. A few days later, the canoe docked at the government pier in Rikitea, Mangareva Island. On September 11, the crew that would sail the Rapa Nui leg set out from Hawaii for Mangareva. Preparations Nainoa: "We are going to the land of the people who I think were the greatest explorers of all time. The Polynesians were the colonizers of the largest nation on earth, but this particular leg to Rapa Nui had to be the most difficult one of them all. I go there in great honor of the people who found this tiny island. On September 11, 1999, on the Hawaiian Air flight to Tahiti, Nainoa is leaning over his seat, talking with crewmembers Shantell Ching and Mike Tongg. They discuss the weather - a series of low and high pressure systems are migrating from west to east along the track they will take from Mangareva to Rapa Nui - and they assess the possibility of riding one of the lows to the east. "It takes about 40 hours for a low to pass and it will bring winds from the west," Nainoa says, "so if we jump off and sail with it, we can extend our time in the low to about 60 hours. At six knots that gives us 360 miles. Getting east may not be as much of a problem as we think, but finding the island, that will be a problem. Rapa Nui is tiny and there will be few if any birds to help us find it. This is going to be a very mentally demanding trip." Everyone in the crew knows the voyage will be unlike any they have made before and they have all prepared themselves for it in unique ways. Aaron Young, for example, stays awake for 20 hours at a time, sleeping three or four, then practices what he calls "keeping busy." "One thing you don't want to do is let yourself get in a rut on the canoe," he says. " You have to find something to do, be helpful, vigilant, look around to see what needs to be done. And to prepare mentally for that, I don't allow myself any sloppy land habits, putting things off, for example. So before I leave on a voyage I get real busy doing chores - it gets my mind in shape for the discipline needed to be on the canoe." Aaron also takes cold showers and increases his already strenuous level of physical exercise. "It's hard to go from a comfortable life on land where you sleep in a warm bed to being aboard the canoe where you are often cold and wet and you take baths in seawater and go to the bathroom over the side," he says. Farther back in the aircraft's cabin, Doctor Ben Tamura, the medical officer, is reading an article entitled, "Preventive and Empiric Treatment of Traveler's Diarrhea," which was written by a colleague, Dr. Vernon Ansdell of Kaiser Hospital, a specialist in travel medicine. How has he prepared himself personally for the voyage? "I tend to get tendinitis when hauling on lines," he explains, "so a few months before leaving I carry a tennis ball in my car. On the way to the hospital in the morning, I squeeze it with my left hand and coming back home at night, I squeeze it with my right to strengthen my arm and wrist muscles." He also spends a lot more time than normal in the sun and he changes his toilet routine. "It's not so easy to go to the bathroom in public," he explains, "so I get myself used to it by changing my routine. I began to use the lavatory at the hospital rather than the private one in my home. You know, on the canoe when you go to the bathroom the navigator is sitting just sixteen inches above you." As on his last two voyages, Ben rewrote his will and spent a lot of time, even though on vacation, "cleaning house" as he puts it - tidying up his office work, sweeping out the garage, mowing the lawn - so he can focus totally on the voyage when its time to leave. He also conducted mental dry runs of what each day aboard Hoküle'a might be like-counting up the number of tee shirts, shorts, towels and underwear he might need.

"I took the last ten days off from work," he explains, "and spent a lot of time surfing. I practiced letting other surfers take a wave, even though I was in position for it, and not getting pissed off when a surfer dropped in on me. Another thing I did," he continues, "was even more difficult - practicing tolerance in commuter traffic." "Voyaging aboard Hokule'a has really taught me a lot about the word love," Ben goes on, "it's a word that is really misunderstood. People think it's about sex or that you can only have real love between a man and a woman. That's not what I'm talking about. My other trips have given me a feeling of what love is in an altruistic sense that I can't put into words easily. It's different than the media or even classic literature portrays love. It's like the word "aloha." How can you define that? There are so many different meanings." Sitting next to Ben on the Hawaiian Airlines flight to Tahiti is Mike Tongg. "I began to prepare about three months before going to Mangareva," he says. "Every voyage is special. I feel like I am a servant of the canoe and, given my age (55 years old) I need to get in shape to handle the sails, the steering, and being in a difficult environment for so long. I also get ready mentally. I need to disassociate myself from the land and prepare my mind for the ocean and I do that by spending more time on boats. I begin to study the clouds and pay attention to the tides, be aware of sunrise and sunset. I try to get back in tune with nature." Mike also reads his old diaries, written on the six previous voyages he has made. He exercises physically and he gets in touch with members of the crew to rekindle, as he puts it, "that bond of 'ohana with the family I will sail with." "The spiritual side of life is real important to me," Mike continues. "The Lord has given me this opportunity for a purpose. In the past voyages, He has taught me that the strength to deal with hardships comes from within. I also look to the leaders of the voyage to learn from them. I see what I call a spiritual intellect in Bruce and Nainoa, for example. They are dedicated and focussed so that is one ethic that I try to emulate. In the past, in order to survive, the navigators had to focus and they needed inner strength. I need the same thing as a crew member, so I try to work hard on that." The crew also needs to practice the philosophy of malama - of caring for the natural environment - of helping to create what Nainoa calls a sense of pono - of balance between all living things and the natural resources of the planet. As Nainoa explained in a recent interview, "The Polynesian genius is the ability to find sustainable ways to only take only as much from nature as nature can provide." "The concept of malama," explains Tongg, "may have evolved from our heritage of long distance voyaging. Our ancestors learned they had to take care of the canoe and that if they did, the canoe would take care of them; they also learned that they had to take care of each other." The malama philosophy is part

of the life of every member of the crew. "When I was younger,"

says Mike Tongg, "voyaging was an adventure - a test - I just wanted

to go, I didn't think about much else, just getting on the canoe. But

now I think about a lot of other things before I go. I think about my

family and being sure they are comfortable with my sailing. I think

about my larger 'ohana, my community, and that all of

us on the canoe represent our islands and our people - maybe hopefully

even the aspirations of all people on planet earth. I think about what

values the voyage has for all of us - both those aboard the canoe and

those at home - the values of aloha, malama, of team work, self discipline,

and of always having a larger vision of why we sail which "This voyage will test us," says Nainoa. "There is no question about it. Each person aboard Hoküle'a and Kama Hele is totally committed to this voyage spiritually, mentally and physically." Pausing for a moment, Nainoa peers out the window. He sees empty ocean below, a route he has sailed perhaps a dozen times. But the voyage to Rapa Nui will be across another part of this ocean - one that is totally new for him and his crew. "In the past when only I was navigating, nobody else really understood the system," Nainoa says, "it was just myself, and I would hallucinate, I would get very near collapse. But this time it would be foolish to do that, and there is no need because we have good navigators. We will have a top navigator on each watch. The navigator will double as a watch captain. Plus, frankly, at my age, I feel not as physically strong as I was twenty years ago. Just not. And being wise about that issue it is good to bring two experienced navigators, Bruce Blankenfeld and Chad Baybayan. While they are on watch, I can sleep and they can steer a course and when I get up they will tell me exactly where we have gone and I will recalibrate my own mental map. I think that's what it's going to take." Bruce Blankenfeld and Nainoa are old friends, they fished together in a small commercial enterprise back in the 70s and Bruce is married to Lita Thompson, Nainoa's sister. "Bruce is the most natural ocean person I think I have ever met," says Nainoa. "Natural - everything is easy for him immediately. No adjustment time. No nothing. He is fine. Bruce changes from land stuff to ocean stuff by becoming extremely relaxed, extremely comfortable." In appearance, Bruce is raffishly handsome. He has curly black hair, deep set eyes under prominent ridges, broad shoulders and thick canoe paddler's forearms. He exudes a quiet self-confidence, a man who has answers to things. "Bruce is the kind of person that without the ocean you would take away half of his life. Nothing in his life would have the kind of importance and value without him having a connection to the sea, he is so innately inclined to the ocean." The other watch captain is Chad Baybayan. Chad stands about five feet ten. A man whose physical center of gravity appears low to the ground, Chad has a swimmer's body, suggesting a capability of delivering powerful strokes and a strong finishing kick. He is dark by genetic makeup (he is part Hawaiian, part Filipino) and because he spends so much time in the sun - running, swimming, physically preparing for long ocean voyages. Chad will readily tell you that sailing aboard Hokule'a has been the seminal experience of his life - accounting for his inner sense of confidence, for the fact that he is about to receive a master's degree in education, for his happy marriage and fatherhood. "Chad is the academic," says Nainoa. "He will study and train incredibly hard and he will get out here and he will force that training, he will force that information, he will mentally, academically, try to figure it out. He has an intensity, but if Chad gets too intense he gets tired. He needs that intensity but has got to find a way so that it doesn't exhaust him." "The reason why we could not do this trip before but we can now is because these guys command so much respect that there are absolutely no questions on the canoe. No debates. Authority has been totally earned by Chad and Bruce so it's easy for anybody to get on board and serve them. That's why it will work. But without that kind of 100% commitment by the crew to this kind of earned leadership this would be, oh man, a tough job. To do this in 1976, forget it."

Tuesday, September 14 - Arrival Rikitea, Mangareva, Gambier Islands, French Polynesia: The Air Tahiti STOL aircraft sweeps in over Mangareva's outer reef, flies low over a frothy turquoise sea stubbled with coral heads, and touches down on a cement strip laid like concrete frosting over the barrier reef. We disembark and collect 72 pieces of luggage shipped as cargo, 23 as baggage and 14 as hand carry - essential supplies for the voyage to Rapa Nui. After a short ride on the ferry, a forty foot converted fishing boat, we arrive in the harbor of Rikitea and moor alongside Hokule'a. Expedition headquarters ashore is in a converted furniture workshop owned by our host Bruno Schmidt. As we unload our gear, heavy clouds scud across the mountain peaks above the village, bringing rain. We rig tarpaulins to shelter the crates of food and other supplies we have brought in from Tahiti. That night, after a Terry Hee dinner of soup, fish stew, teriyaki meat and rice, Chad Baybayan welcomes us to Mangareva. "I'm glad you are all here safely," he tells us. "Once we have accomplished a few chores we will be ready to jump off for Rapa Nui." A lot had already been done. On the wall behind Chad, written on a large sheet of paper, is the work list: Unload canoe and wash galley

utensils, tupperware, water bottles Many of the items have already been checked off. After Chad's welcome, it is Nainoa's turn to speak. "I'm not going to kid you," he tells us, "this is going to be a tough trip. But looking around at all the folks assembled here, I know that we are going to make it and do it well and safely. I'm not saying that we will find Rapa Nui because that would be arrogant, but I am sure that if anyone can do it, we as a group can do it." On the wall behind Nainoa are a series of weather maps from the French meteorological station on the hill overlooking the harbor. The maps show a succession of low-pressure systems that have moved in an orderly procession over the South Pacific in the last week. Today's chart shows a long front has formed between a low to the south of the island and a high to the northeast. As he talks, Nainoa runs his finger along the front. "Today, we flew into this weather on the way down from Tahiti," he explains, "and we had turbulence and clouds most of the way. This front is causing the weather we are experiencing now." Nainoa pauses to examine the maps for the previous two days, mentally calculating the front's direction and speed of motion. "I think the system is moving east southeast along the line defined by the front at about 16 knots," he explains, "so that if it continues in that direction it might pass in about two or three days and be replaced by another low pressure system which may bring in westerly winds, just what we want. I've only been here two days, so I can't be sure, but if that happens I think that we had better be ready to go on Friday. It's too early to predict the weather accurately, but I can tell you one thing, when the wind is right, we're going to leave." As the meeting breaks up, the crew who will sleep in the workshop lay out sleeping mats in nests they have created among crates, coolers and folded sails. The rest depart to bunks aboard Hokule'a or Kama Hele. A south wind sweeps in over the harbor of Rikitea stirring whitecaps. Rain slants across arc lights bathing the canoe and the escort boat as they pull against their mooring lines, bobbing and yawing in the choppy water of the harbor. Thursday, September 16, Rikitea In the last two days, the crew has been busy checking and packing gear and going over safety procedures aboard the canoe and the escort boat, preparing for possible heavy weather. Star maps have been laid out and the navigators - Shantell, Nainoa, Bruce and Chad - have been rehearsing the star alignments they will use for determining the latitude of Rapa Nui. Today, Hokule'a is brought alongside the pier so that gear can be loaded and Kama Hele takes on water and fuel. Tonight, most of the crews will sleep aboard Kama Hele and Hokule'a to be ready for departure at short notice. Today is also "Hokule'a Day" for the students of the Centre d'Education au Developpement - a vocational/technical school established by The Brothers of the Sacred Heart, a religious order from Canada. Chad conducts class for the sixty students at the school, after which Tava Taupu leads a tour of the canoe. The students, eighteen from Rikitea and the rest from the outer islands, learn the basics of steering by the stars and what life will be like aboard the canoe on the voyage to Rapa Nui. The most frequently asked questions: "Where do you sleep?" "Where do you go to the bathroom?" "How do you steer the canoe?" And, "How does the man overboard beacon work?" Nainoa, Chad and Bruce have been making regular trips up to the weather station to analyze the daily weather maps. We have experienced fairly steady southern winds, heavy clouds and occasional torrential rain. The prediction for yesterday was that the rain would stop today (which seems to be happening) and the wind will begin to back around to the east, then northeast - beginning its journey around the compass to the west, just what we want, perhaps by Friday or Saturday. But no one can be sure. It's also possible that a high-pressure system may join with a stationary high over Rapa Nui, establishing trade winds over the entire route to the island, which will mean constant tacking. And there is a weak low pressure system forming to the east, in the path of the front, which may cause it to stall over Mangareva. This might delay the wind shift that we need to sail to Rapa Nui without tacking. The situation remains uncertain. "So, what else is new," says Nainoa, who has seen this kind of uncertainty dozens of times before. The Story of Anua Matua Later in the day, our island host - Bruno Schmidt - arrives to take us to the other side of the island to speak with a man who knows many ancient Mangarevan legends. We find Teakarotu Barthelemy at his home amidst a grove of orange trees near the beach. A man of ample girth and impressive dignity, he sits on his lanai overlooking the ocean and tells the story of a great Mangarevan navigator who set out to find Rapa Nui, just as we will do when the weather clears. "Anua Matua chose his crew and set out," Teakarotu explains. "He arrived at an island that is called Maka Tea and gave it the name of Pua Pua Moku and he left his daughter and her husband there along with some of his crew and sailed on to the island now called Elizabeth and also gave it the name of Pua Pua Moku. After that they sailed on to Pitcairn Island, which he gave the name of He Rangi. During the voyage they searched for Rapa Nui but they passed it by mistake and found themselves in a cold place which they called Tai Koko. This place is called Cape Horn today. They realized that they were not at a good place so they turned back and sailed by the stars in the direction they came to try and find Rapa Nui. "Te Angi Angi was now the navigator and captain. When they finally arrived at Rapa Nui they gave the island the name of Mata Ki Te Rangi which means "the eyes look at the heavens," and another name of Kairangi which means "eating the sky'" and they also called the island Pourangi which means "pole eating the sky." "To understand the reason for the names," Bruno explains, "you must think what the island looked like to them as they approached from the sea. They saw a tall mountain thrusting up into the sky as if it were eating the sky and their eyes, following the mountain, were looking at the heavens." Teakarotu learned the legend from his grandmotherToaatakiore Karara who was a famous singer and kahu of ancient traditions. Toaatakiore helped Sir Peter Buck, when the famous anthropologist visited the islands in the 1930s with a Bishop Museum expedition, by singing over 160 songs for him. Oral traditions are subject to a great deal of change over the years and it is probable that the legend, as told by Teakarotu, is not as accurate today as it was in the days of his grandmother. The islands listed, for example, cannot be identified today. According to Bruno, Maka Tea means "elevated atoll," and Tai Koko, which Teakarotu identified as Cape Horn means "place of heavy seas." Teakarotu also told us that Te Angi Angi called Rapa Nui by the name of Te Pito Te Henua, but this seems doubtful because, as Bruno says, this is a Tahitian name. But the legend is interesting because it suggests the great difficulty that even the ancient navigators experienced when trying to find Rapa Nui. It also suggests that at least one canoe may have strayed past Rapa Nui and discovered the great continent of South America.

The navigators are getting to know Guy Raoulx pretty well. He is French/Tahitian, short (about 5 foot six) and wiry - a man of intense energy. Guy is the Chef Meterologiste of the weather station and as such is entitled to a home overlooking the lagoon and a limitless expanse of ocean. Today we can only imagine his view because the front continues stalled over Mangareva and where the lagoon should be we can see only rain and cloud. Guy has served in the meteorological service (the French call it the Meteo) for about 25 years, spending time, to his great delight, at almost every station in French Polynesia. Thinking about Guy's travels and his rent free house overlooking the lagoon causes Chad Baybayan to proclaim, "I could do this." Every day, at about 11 AM, Guy launches a weather balloon from a hanger the size of a one-car garage perched above the harbor on the slopes of Mount Duff. Today we watch him as he squats in the hanger's open door, the balloon in his left hand tugging for release. "I am waiting for a lull in the wind," he explains. A few moments later he sprints out the open door and - with a ballet dancer's pirouette - launches his balloon. He returns to the hanger, grinning, apparently as delighted with his performance as we are. "That was a good one," he announces, "but you should see what happens when the wind comes from there (pointing out toward the sea). No matter how far I run before launching - bam - it goes into the trees. And sometimes it takes off quite unpredictably. I have had it crash into the instrument tower more than once, wrapping itself around all the antennas. What a mess." Guy's monologue is accompanied by expansive pumping and waving of arms, a repertoire of gestures expressive of his Gaelic genes. The news posted by radio signals from Guy's balloon as it ascends though the atmosphere at 200 meters a minute, is not good. Just as Nainoa feared, the weak low pressure system forming to the northeast of Mangareva has, if anything, intensified - stalling the passage of the front - pushing it back even. The forecast is for continued unsettled weather. By Saturday, the front may pass to the east bringing favorable winds from the northeast but also continued clouds and rain. Nainoa, staring out the door of the Meteo says, "I look out here and I can't even see the islands a mile away. There is no way we can navigate in this stuff." Guy's weather maps show a trough of low pressure pushing down across the island like the impression of a giant thumb. The thumb is predicted to move east by mid-day on Saturday, allowing the winds to begin to haul around to the west, southwest, and south - all favorable for a direct run across to Pitcairn Island. But will the prediction hold? And, if it does, how long will the winds remain in a favorable direction before continuing to round about and begin to blow in our face? Sunday, September 19, Rikitea On Friday, the town had a party for the crew to say goodbye so that we would be free to depart at short notice. Saturday night the crew and our hosts enjoyed a special dinner at a local restaurant. The crew has been working aboard Hokule'a for the last few days. Sails are rigged, the gear stowed away, emergency drills have been performed and the new crewmembers have blended with those already here. Kama Hele is provisioned and fueled. Sunday dawns with a partly cloudy sky and a light wind from the northeast. The crews of Kama Hele and Hokule'a have moved their personal gear aboard to be ready to sail at short notice. At about four PM, we receive word that we should be ready to depart for Rapa Nui tomorrow at first light. All of us are excited by the prospect ahead - to participate in one of the most important of voyages in Hokule'a's nearly twenty-five years of sailing. Monday, September 20, Rikitea Monday dawns with slack winds. The surface of the ocean is like a lake. The sky is almost totally overcast. The hoped-for favorable winds and clear skies do not materialize and so departure is cancelled. The crew stands down and, after breakfast at the beach house, go about various chores. On Hokule'a, Bruce Blankenfeld briefs the crew on procedures for safety at sea. Ever since the unfortunate

loss of Eddy Aikau during the 1978 voyage, safety has been paramount

aboard both Hokule'a and her escort. Each crew member is issued their "Safety is our most important consideration at sea," Bruce tells the crew. "We must always be on guard against any kind of accident. Always watch out for everyone on the canoe. Overlook nothing. Be vigilant at all times." Both Hokule'a and Kama Hele are now ready for sea, waiting only for favorable winds and clear skies. The first leg of the journey to Rapa Nui will be to Pitcairn Island, a little over 300 miles away. Once having found Pitcairn, the navigators will begin the voyage to Rapa Nui from a known point in the ocean. "Getting to Pitcairn is very important," Nainoa told us in a recent crew briefing, "so I want to leave Mangareva with both favorable winds and a clear sky so that we can navigate. We will just have to be patient and wait until the conditions are right. But, as soon as they are, we will jump off."

Kama Hele Kama Hele-The Ultimate Escort Vessel Chad Baybayan: "We are committed to learning and exploring about our voyaging history, but we're committed to doing it safely. In 1978 there was an accident where we lost one of our crewmembers. That experience taught us a very, very painful lesson, that safety is paramount to everything we do. That's why we train so vigorously to prepare the crew to sail safely. That's why we do swim tests to make sure that we're safe if we have to go in the water, why we practice man overboard drills so that we can recover anybody that falls in the water within two minutes, and why we have escort vessels that follow us." Hokule'a's escort boat is a 45-foot steel sloop called Kama Hele - the floating home of Elsa and Alex Jakubenko. Kama Hele was built by Alex, who first began constructing sailing yachts and fishing boats in Australia in 1949. "Kama Hele" means "Traveler" as well as "A strong branch off of the trunk of a tree." The sloop has accompanied Hokule'a on its last three voyages (1992, 1995, and 1999). Alex and Elsa's first encounter

with The Polynesian Voyaging Society began in a roundabout way in 1972,

when they moved to Taiwan to build a 65-foot ketch, Meotai. Meotai was

launched in 1974 and eventually purchased by Honolulu business man Bob

Burke who used her as Hokule'a's escort vessel on the first historic

voyage When Hokule'a arrived in Tahiti, Alex and Elsa were there aboard another Jakubenko built sloop called Ishka. "I saw the tremendous reception that the Tahitians gave the canoe," Alex remembers, "you would have to be there to believe it. Within twenty-four hours there were at least twenty new songs about the canoe. The voyage gave the people so much pride and excitement that both Elsa and I wanted to do something to help. But at the time, we had no idea what." Later that year, the couple returned to Hawaii where Alex worked at Kehi Dry dock (where Hokule'a was brought for overhaul after the 1976 voyage and for repair after she capsized on her 1978 trip to Tahiti.) In 1980, Alex and Elsa began using Ishka to escort Hokule'a. While towing the canoe to Hilo for her departure to Tahiti, Ishka and Hokule'a were struck by a terrible storm. Even with her engine going at full speed, Ishka could not make headway and, for a time, the two vessels were in danger of being destroyed on the Big Island's Hamakua coast. Fortunately, good seamanship on both escort and canoe saved the day. "If it were not for Ishka and Alex, Hokule'a might not be here today," says navigator Bruce Blankenfeld. This near disaster would provide valuable experience once Alex began to build Kama Hele. Sailing aboard Ishka, Alex and Elsa were with Hokule'a all the way on the 1980 voyage to Tahiti during which Nainoa, under the watchful eyes of Mau Piailug, navigated the canoe for the first time. During the next ten years, while other escort vessels followed in Hokule'a's wake, Alex turned his attention to building steel trawlers, but he kept thinking about his experiences and the unique needs of the escort mission. In 1991, When Nainoa asked him if he would escort Hokule'a on the voyage to Rarotonga for the Arts Festival in 1992, Alex said yes. But he would do so with a completely new vessel, one custom built for escort duty. In 1991, Alex laid the keel for what he hoped would be the "ultimate escort vessel"-Kama Hele. Working with a basic design by marine architect Bruce Roberts, Alex made many changes to adapt the vessel for her duties. "When I thought about the design of this vessel," Alex says, "I tried to remember everything that we did right with the earlier vessels and ways to improve on our mistakes. The vessel had to meet all the requirements of escorting the canoe so that it would never fail in her mission, and that meant being able to take a tow in all kinds of weather." In addition, the escort had to be small enough so that she would not overshadow the canoe yet large enough to carry sufficient fuel for the duration of the trip. "She should also have plenty of room for her crew," Alex explained, "and, if necessary, for the crew of the Hokule'a. And she must be fast enough so as to never slow down the canoe." The vessel that took shape in Alex's yard - Hawaiian Steel Boatbuilding - was a 45-foot sloop with a graceful sheer line from bow to stern. She was equipped with fuel tanks that could carry 1700 gallons of diesel, enough to allow her to steam up to 5000 miles without refueling. Kama Hele is powered by a Detroit 371 diesel engine that Alex describes as "old fashioned, the kind they use in tanks or landing craft, but it will go forever and it is simple to maintain." The engine turns a propeller that is 29 inches in diameter, at least three times the normal size, which Alex appropriated from a 44-foot tugboat. Kama Hele carries a desalinator capable of producing 40 gallons of fresh water a day, more than enough for the crew of the canoe and escort combined. She is also fully equipped with the latest radio and navigational gear. "The wiring was a difficult job and I needed help for that," Alex explains, "so Jerry Ongias came down and spent a lot of time making sure that everything was done just right." Also assisting Alex to meet his launch deadline were Paul Fukunaga and Jeff Merrik. In 1992, on schedule, Kama

Hele departed with Hoküle'a and set her course south to the Cook

Islands, returning to Hawaii after a successful voyage. In 1995, Kama

Hele once again headed south, this time in the company of two canoes,

Hokule'a and Hawai'iloa, on yet another voyage to Tahiti where they

would join up with a fleet of canoes from the Cook Islands, Aotearoa

(New Zealand) and Tahiti, as well

as one other canoe, Makali'i, from Hawaii. Departing Tahiti on the return

trip, Kama Hele proved her mettle as a mini tug by towing two canoes

simultaneously, Hawai'iloa and Te Aurere (the Måori canoe), from

Tahiti to the Marquesas - all the way into strong headwinds. From the

Marquesas to Hawaii, Kama Hele escorted Hawai'iloa and shortly after

reaching port, she turned around and escorted the Cook Island canoe, "Elsa and Alex are at sea more than any of us," says Nainoa. "They have both proven over and over again that they are totally committed to the mission of our voyages." "You might be able to find someone else to go on escort duty who had a good boat," says Bruce Blankenfeld, "but you would not find a captain like Alex. When he says he will do something, you can be absolutely certain that it will be done." In 1998, when Nainoa once again asked Alex and Elsa if they would agree to serve one last time, the couple could be forgiven if they had demurred - they were then both in their late 70s. But, after due consideration, they agreed to take on the challenge.

Makana - a story from the voyage to Rapa Nui A few hours before our departure from Mangareva, I am riding in the back of our host Bruno Schmitt's Land Rover with Makanani Attwood and a large sandstone slab with strange symbols etched into its surface. Makanani is an elfin man in his forties. He has a pointed beard and a gleam in his eyes, which seem to explode with mirth when he speaks, which he does now in non-stop commentary on the meaning of life, the voyage to Rapa Nui, his ancestors, and the significance of the slab we are conveying to a garden in front of Bruno's house. "This is a traditional way of recording a historic event," Maka explains. "It's a petroglyph which I carved to give to Bruno in return for his hospitality in Mangareva. It's a mo'olelo, a story, which could easily be oral, in an oli or chant, but in this case it's carved in stone." As the truck bumps along Rikitea's main street past the gendarmerie and the post office, Maka runs his finger over the design he has etched into the stone. "Here is a representation of Hokule'a, and this is Kama Hele. Here is a mano, a shark, which is one of our ancestral guardian spirits, an 'aumakua. I chose the mano because it's an 'aumakua common to many of the crew members sailing on the two vessels. And there's another reason: when Hokule'a passed through the reef surrounding Mangareva, a number of crew members saw a shark swim directly in front of the canoe. Timmy Gilliom saw it clearly. The shark seemed to be guiding us through the reef and as soon as we got through safely, it disappeared." The Land Rover now bumps over a dirt road. We pass the technical school created by the Brothers of the Sacred Heart and arrive at Bruno's bungalow which is set on an ample lot bordering the ocean . We unload the petroglyph and the three of us struggle to lug it to Bruno's garden. With Bruno and his wife, Maka continues his explanation of its significance. "I also carved a mo'o, a lizard, which is a land 'aumakua. The mo'o lives in freshwater streams, so now we have here both a land and an ocean 'aumakua, a lizard and a shark, which represent the fact that all life depends on the land and ocean, which is a typical way that all island people think." Now Maka points to a checkerboard of sixty-four depressions. "This is a konane board. Konane is an ancient game of kings which is equivalent to chess. Konane is symbolic of wisdom; it makes me think of the need for our leaders to plan carefully to care for our land and our ocean, to malama our natural resources. One goal of our voyage to Rapa Nui is to encourage all of us to respect our natural world, the sea we sail over, the islands that we sail to." For a time we all sit quietly, admiring Maka's petroglyph and Bruno's garden. It is silent except for chickens squawking in a nearby henhouse and Bruno's sheep bleeting in a nearby pasture. Maka is usually in constant motion but now he seems serene. The petroglyph is the last of many gifts he has presented to our Mangarevan hosts. Since his arrival on the island, he has carved about three dozen nose flutes which he presented to children all over Rikitea. He also made a Konane board for Bianca and Benoir, a couple who hosted a reception for the crew. And from the crooked branches of trees he made and gave away many lomi sticks - a traditional implement to massage the body. "I don't have money for t-shirts to give away, so I make things on every island we visit. These gifts are what we call Makana, an exchange from one seafaring family to another to memorialize and enhance our cultural integrity. They are given in simple appreciation for the hospitality we have received. They are a part of our ancestral protocol of meeting and greeting one another as a family of seafaring people. Our voyages are also what we from Hawai'i offer as our gift to the people of the islands we visit. Voyaging is about the spirit of exploration and the renewal of our culture. They say we have not forgotten our Polynesian heritage; they say Onipa'a stand fast." I ponder Maka's words now as I sit quietly in Bruno's garden, sharing a moment that transcends time. Maka's petroglyph memorializes both the heritage from our past and the hope for our future as island people united by an ocean we all share and a common urge to sail upon it. In about an hour we will rejoin as a crew, offer a prayer for the success of our voyage, and set out to find Rapa Nui .

Tuesday, September 21 - Departure At 1:45 p.m. Hawaii Standard Time, with pu blowing ashore and on Kama Hele, Hokule'a leaves Rikitea Harbor under tow. We depart under a leaden sky but by the time we pass through the reef the clouds dissipate. At 4:05 p.m. Hokule'a drops the tow and takes position ahead of Kama Hele. With its GPS turned off, the escort boat will follow the lead of the Hokule'a's navigators for the rest of the voyage. Stratus clouds darken the sky behind us over Mount Duff. Cumulus clouds form ahead of us, in the path of the canoe and squalls march across the horizon - nasty green splotches on Kama Hele's radar screen. Just as the sun sets, crewmember Max Yarawamai arrives aboard a local fishing boat from the airport. He completes the canoe's crew of 12. The night is sheened with silver moonlight. We see Temoe island pass abeam to port, or at least we see indications of the island - a sharp ivory line of surf followed by a darker line, the beach, and a waving fringe of color that must be stands of coconut palms. The wind blows from the N or NNW at about 15 knots. The swells are heavy.

Nainoa Thompson Nainoa's Thoughts Just before

Leaving: "The weather will be difficult. "The pattern that has established itself in this area is a day of good weather, then the approach of a low and a couple of days of rain. Today is in-between, good weather and rain. Tomorrow and Thursday we may have good weather but I bet it will go bad again. Friday I think we'lll get rain. I want to leave now, otherwise we will have to wait until sunrise tomorrow to get through the reefs - another eighteen hours of delay. In eighteen hours we will go eighty miles toward Rapa Nui and the farther we sail east, the longer we will stay with the good weather. "I'm excited. We have been preparing for this voyage all our lives, we just didn't know it. All of our studying, the academic side of our preparation, has really just laid the foundation for what is inside us, the other ways that we understand the world. I think back on times with my family when I was a young kid, and all the time that I have spent on the ocean. All of this has prepared me for thinking about the ocean and the heavens and the environment, learning about our culture and our history and our heritage, learning about being at sea, learning about the canoes and about each other. I believe we are on the eve of tremendous growth as a crew. So I'm both excited but also apprehensive about the difficulty of the trip ahead of us. This trip is going to be very difficult navigationally because of where we're trying to go and because of the weather. The weather is now becoming a real factor. "I didn't expect tropical lows forming and then dissipating around Mangareva. I expected subtropical lows forming to the south of us and moving to the east. They are there but that is not what is affecting us now - we are getting tropical lows from the north and that brings100 percent cloud cover, rain, changing winds and squalls. "I think that we will be able to use some swells to navigate, probably from the south, but it depends on where the lows are situated to the south of us. They are the only weather systems that will build waves. The swells will come from low pressure areas at thirty five or forty degrees south. As long as the fetch (the area over which the wind blows) is long enough, the lows will generate swells that we can use, but will we be able to read them? We have to go to sea to find out. "The moon is big now. It is waxing, the full moon will be on September 25th, and that will be a help. I think the skies will remain overcast, about 70 - 80 percent, but if it stays like this or improves we can navigate. We have a big moon that will rise at about 2 p.m. When the sun goes down we will have Jupiter and Venus. The moon has a 'cut' to it, an edge, so we can tell where north is - the horns of the moon, tip to tip, point north, especially on the equinox. So the cut of the moon will help tell us where north is when the moon gets high. And I'm hoping that tomorrow the visibility will improve because that's the weather pattern we're in. The weather was bad yesterday, so hopefully it will be better tomorrow, but we don't know. But at least we'll be 100 miles along on our voyage." "Learning is all about taking on a challenge, no matter what the outcome may be. When we accept the challenge we open ourselves to new insight and knowledge. In the last few days, I have just tried to be quiet and to study - that's how I prepare. I am thinking all the time about home, about the voyage, the weather, the crew, about what we have to do to make this work. "I think about home a lot because that's why we do this. We love our homes, we love our people, we love our culture and our history, and we want to strengthen them. This is our opportunity, our chance to do something to support all those who care about these things. I want to thank all the people who gave so much to allow this voyage to take place, but who are not here now. They allowed us to take the risk, to do all of this. I want to thank all the families and children involved for giving us the chance to go. This voyage is about people - it's about all our people. "When I think back on my life, it's clear that I had no way of knowing that I would be here now doing what I am doing. When I began studying in school and gaining knowledge, I sometimes doubted the importance of that effort. But it's the knowledge that I gained with the help of so many teachers that is allowing me to do what we are about to do. "So I hope that all our children will keep on pursuing knowledge. None of us knows where we are going, but at some point in our lives, that knowledge will allow us to jump off into the unknown, to take on new challenges, and that's what I consider before every one of these voyages - the challenge. Learning is all about taking on a challenge, no matter what the outcome may be. When we accept a challenge, we open ourselves to new insight and knowledge. "When we voyage, and I mean voyage anywhere, not just in canoes, but in our minds, new doors of knowledge will open. And that's what this voyage is all about. It's about taking on a challenge to learn. If we inspire even one of our children to do the same, then we will have succeeded.

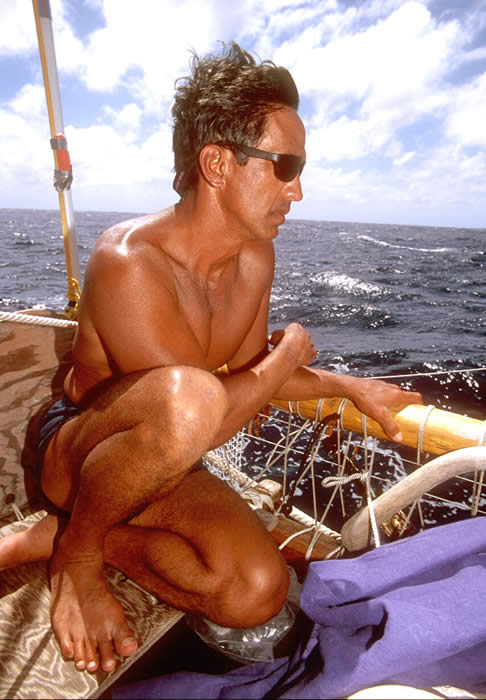

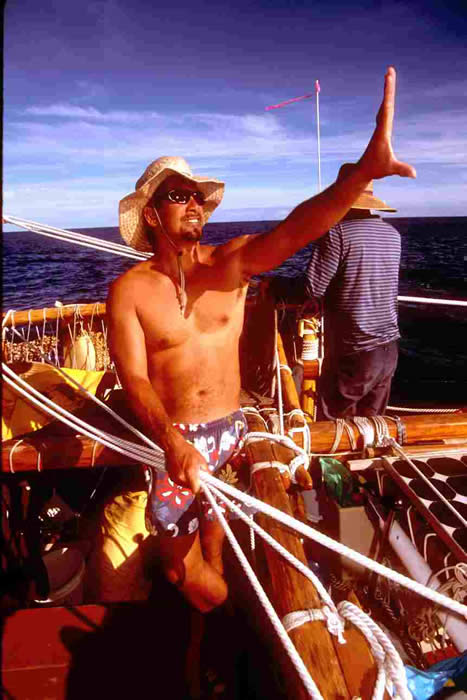

Bruce surveys the ocean from Hokule'a's foredeck A Difficult Voyage Any voyage without charts or instruments is, of course, extremely difficult. For a compass, Nainoa, Bruce and Chad use the rising and setting point of stars. Waves also provide clues to steer by - the southwest swell, for example, that Hokule'a encounters as soon as she departs Mangareva. Generated by storms near Australia, 4500 miles away, it is satisfyingly deep and constant. Longitude cannot be found without a chronometer, so the navigators rely on a system called, appropriately enough, "dead reckoning." They estimate the time and speed they steer a given direction and, on a mental map, they place themselves along an imaginary course line toward their destination. Latitude is determined by estimating the altitude of stars as they cross the meridian, their highest point of rising. In all of these calculations, errors naturally accumulate. "We can dead reckon our distance traveled, if we are careful, with maybe a 10% error, and we can guess our latitude with an error of about plus or minus one degree," Nainoa says. I do the math in my head - 10% of 1500 miles (the distance east- west from Mangareva to Rapa Nui) is 150 miles. Two degrees of latitude (along a north-south line) is 120 miles. So that produces a box of accumulated error equivalent to 18,000 square miles. Finding the tiny island of Rapa Nui (12 miles wide by 7 long) in that vast space seems at best improbable - but that's a personal opinion, which I keep to myself. Rapa Nui's isolation presents yet another problem. On all their previous journeys, Nainoa and his comrades have never actually tried to find a single island, but have rather aimed their canoe at a chain of them. Tahiti, for example, is part of an island chain that stretches across some 400 miles of ocean - a navigational safety net. But on this voyage, there is no safety net. Rapa Nui stands alone in an empty sea. "One thing has always been certain," Nainoa once told us, "if we looked at this voyage scientifically there is almost no chance of finding Rapa Nui. If we thought that way, we would not have chosen to go. But you know what? I bet we find it!" Nainoa's first target is Pitcairn Island, about three hundred miles away, one of the few stepping stones along the route to Rapa Nui. Enroute Pitcairn For two days, the wind continues out of the NNW and Hokule'a plunges through steep swells toward Pitcairn. The crew acclimatizes themselves to the pitching world of the canoe and a renewed intimacy with the forces of nature. Although most of the sailors aboard are veterans of many voyages, it has been at least four years since Hokule'a's last deep ocean passage and even the most experienced crew are a little rusty. During the relatively short hop to Pitcairn, Nainoa emphasizes the importance of steering a steady and accurate course. "Over the years, I have learned that a good steersman is worth his weight in gold when you're trying to go to weather," Nainoa says. "Steersmen who don't have the feel steer too much and they fall off. They don't sense the speed. They drop off the wind and sacrifice angle, or they go too close to the wind and they sacrifice speed. They have got to pay attention. Fifty percent of the problem we have with steering is that a lot of people have difficulty concentrating for long periods of time on the canoe's relationship to the wind and the sea. And that's going to be key. You can imagine. We need every single inch. It will drive us nuts if they can't steer properly. With Bruce and Chad on watch we can be sure everyone will pay attention." Friday, September 24- Pitcairn We arrive at Pitcairn on the back of a steep swell aboard a silver aluminum speed boat piloted by Jay Warren - the island's mayor, constable, conservation officer and just about everything else. Jay seems to aim his boat directly at a cliff at alarming speed but, at the last possible moment, he turns abruptly to the left and ducks behind a steel and cement breakwater into a calm but tiny harbor. The island is small, a finger of volcanic rock jutting out of the sea. Our time here is short - a few hours. Even so, Pitcairn gives us many memories: " Of dirt roads, the

color of chocolate, rising precipitously from the harbor to houses that

perch over steep cliffs and look out upon a vast and empty sea.

Hokule'a Sunday, September 26 - Enroute Rapa Nui The wind began to accelerate while we were anchored at Pitcairn and continued into the bright moonlit night of our departure. Yesterday at dawn, the sky was clear with precisely etched fair-weather cumulus clouds spreading across the horizon. Today, the cumulus is replaced by what Nainoa calls "smoke" - gray haze, the result of salt and sea spray stirred into the atmosphere by strong winds. This indicates that we may expect both strong winds and our favorable progress to continue for a while. At sunset today, both canoe and escort plunge through seas frothed with whitecaps. In 25 knots of wind, Kama Hele spreads more canvas and increases the speed of her diesel engine to keep up with the canoe. We hold about the same course we followed on departing Mangareva, roughly east, but we are going much faster. A dark golden moon breaks the horizon and rises above a tumultuous ocean. The moon is a perfect circle and Hokule'a is framed within it, an image as flawless as the voyage has been so far. Hokule'a and Kama Hele breast heavy swells, taking spray over their decks. Rapa Nui lies about 1000 miles dead ahead. Aboard Kama Hele all of our electronic navigation instruments are turned off. We follow in Hokule'a's wake as a second canoe might have on an ancient voyage of exploration and discovery. We are sailing a course that two whale ships sailed a few months and almost a century and a half earlier. Dr. Ben Finney studied the logs of the ships and noted they were able to make the passage from Pitcairn to Rapa Nui in eight and a half and seven and a half days, respectively. Both voyages occurred in late July. The first whaler departed Pitcairn on July, 19, 1850, and arrived off Rapa Nui on July 28. The second left Pitcairn on July 20, 1851, and saw Easter Island on July 28. Both vessels experienced winds that circled the compass during their passages, beginning to blow out of the NW and veering counterclockwise, probably with the passage of a low, first to the west, then south, then east, then back again to north and northeast, but during both voyages the wind prevailed from the northern quadrant. Today, almost 150 years later, we sail the same route, riding the same northerly winds as we make our way east. During the night on the 10 p.m. - 2 a.m. watch aboard Kama Hele, Kamaki, Tim, Makanani, and Kealoha were inundated three times by large swells, breaking into the cockpit. Makanani interpreted the swells to be "our aumakua guiding us, as if by magic, to Rapa Nui." Hokule'a changed jibs twice

in the last 24 hours to adjust to fluctuating wind speeds. "Our crew of veteran sailors are doing an excellent job of steering," reports Baybayan. "We have been blessed with fair winds so far and we are praying that they stay with us a while longer." Monday, Sept 27 - Report from

Nainoa "My original sail plan called for us to leave Mangareva early enough to find Temoe during daylight. My decision to leave in the afternoon was based on instinct. It meant we accepted the risk of trying to find Temoe at night, but I was pretty confident because we would have bright moon light. As it was, we passed Temoe close abeam at about 8:30 p.m. and we could see the surf breaking on the reef and the trees on the island, almost as clear as day. "I was concerned about the Pitcairn leg. I hadn't been at sea for a long time, and I felt pretty rusty. I wondered how long it would take to get mentally and spiritually into the navigation. Finding Pitcairn restored my confidence; it also allowed us to begin our navigation anew from a known point in the ocean, but now 300 miles closer to Rapa Nui. "When everything is going right, I get into a zone, a special place in which all of my relations with the canoe, the natural world and the crew are integrated. I felt pretty disjointed at first, but when we found Pitcairn I began to relax and feel like I was getting into the zone again. "Originally, we thought we might pass close by Henderson Island as another known point farther along toward Rapa Nui, but because the wind would not let us sail high enough to the north to make Henderson easily, we decided to bypass the island and continue straight on. Right now we're in an incredibly good position. We have a low pressure system behind us and tracking with us. This system is drawing the wind down toward us from the north. We are also beginning to see big waves from the east and east-northeast, so I think the easterly trade winds are close ahead of us. "Last night at sunset, I thought the low pressure trough was close behind us, but now it seems to be traveling away from us, or it may be just dissipating. A sign that this may be happening is that the humidity is going down. I don't feel as sticky as I did before. The air is getting colder and drier. A low pressure area is associated with high humidity, and a high pressure area with dry air, so we may be leaving the low behind and approaching an area of high pressure. "Yesterday the sky to the southwest was dark brown on the horizon. We saw thick low clouds, mixed with mid-level stratocumulus clouds - a sign of an approaching cold front associated with the low pressure system. But today the clouds seem to have lifted and the winds shifted a little more to the east. The day before they were more to the north. A typical wind pattern - when a low passes through this area - is for the winds to clock around the compass, turning north to west to south and then back to the east. But this doesn't seem to be happening because the winds, instead of going from north to west, seem to be shifting from north to the east. "Earlier, I was concerned that the cold front might catch up to us, bringing 100 percent cloud cover. We would have no stars to steer by and the seas would become confused. And even worse, if the low were moving slowly east along with us, as it seemed to be doing, we would be in it for a long time. But it doesn't look like that's going to happen. "This voyage is a learning process for all of us. The weather we expected based on average conditions in this area is not what we're getting. To learn, we have to be flexible, to adjust to new conditions, and that's what we're trying to do now. This area is new to me, so any predictions I make are just guesses based on past experience in other areas of the Pacific. As we move along, we are gaining more experience with this part of the world, so our guesses will get better and better. "The trough of low pressure behind us has been a gift. It has allowed us to get a good jump to the east, which is what we hoped for. But at best we thought we might get a jump to Pitcairn. We never dreamed we would be able to sail almost one-half of our voyage on a single port tack. If you look at the map of our sail plan, you will see that it shows we expected to be tacking against the wind, zigzagging to try to get east. But here we are sailing to Rapa Nui in a straight line. If you ask a meteorologist why this is happening, he will tell you that a low pressure area to the west is cutting off a high pressure system and bending the normally easterly flow of winds down to us from the north. "But others might see it as mana, or a blessing from the gods. Before we left Hawaii, Mahina Rapu from Rapa Nui told me, "Don't worry. Your ancestors will take care of you." And when we held a press conference before departure, I told a group of school children from Kamehameha Schools about my anxieties over the voyage, and they told me that the gods would be with us. It's interesting that there are such different explanations for the wind which has been so favorable to us. "Now we have passed any islands we might have used as stepping stones toward Rapa Nui (on the night of Sept. 26, Hokule'a passed Ducie Atoll, which lay to the north along 125 degrees W), and we are embarked upon the open ocean portion of our voyage. Our first task is to get to east, and we have done well so far, but we still have to remember that we have five hundred miles to go before the next segment of our voyage - the search pattern for Rapa Nui. That's the next big challenge. "This morning I feel completely in the zone. You have to be in that special place to navigate well. When you are in the zone, you feel ahead of the game. You find yourself naturally thinking about what will happen next and you are acting in the future, not reacting to things in the past. You have the star patterns in mind and you seem to know where you are even when the sky is cloudy and you can't see the stars. You begin to anticipate the weather. It's an awesome feeling but it's hard to describe. It's like being inside the navigation, participating from the inside. "One big reason why this can happen is because we have such an awesome crew - a dedicated professional team which allows us to keep driving forward without a single hitch. I've never before had the luxury of sharing the navigation with two skilled and deeply experienced navigators like Chad and Bruce. We share ideas. We ask questions of each other. And we come up with collective solid decisions. We share the load and as a result I have never before felt so rested on a voyage. "We have been very fortunate so far but this voyage isn't even half over. Even if we continue to be able to make our way east as efficiently as we have so far, one of the most difficult of our tasks lies ahead - finding the island.

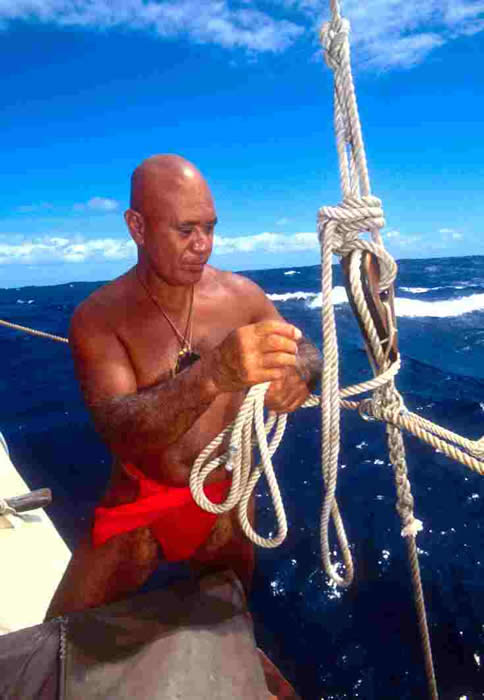

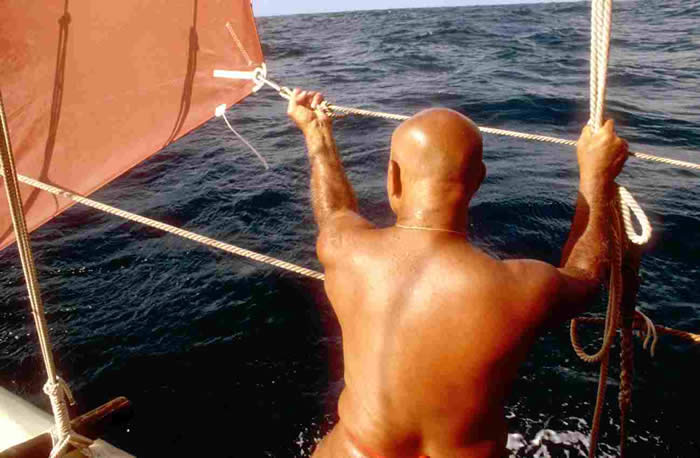

Tava Taupu adjusting the shrouds Sunset, 6PM, September 27 - Navigator's report: Sunrise, Tuesday, Sept. 28 Sunrise, 6AM, September 28

- Navigator's report: Sunrise: The ocean is a dark gray-blue and the sky is the color of lead as we continue to sail east toward Rapa Nui. During the evening, the canoe and Kama Hele hove to in a passing squall. Now, the sun rises behind clouds ahead of us and we trim our sails in gusting winds. Sunset: Hokule'a continues east under a dark sky that offers no celestial clues to direction, buffeted by fast moving squalls. Nainoa waits patiently for the moon to provide a secure sign to steer by, but rain and clouds are so thick that the moon never appears. The crews of the escort boat and canoe endure a long night, alternately raising and taking in sails as the vessels contend with roiling, tempestuous seas. Sunset, 6PM, September 28 - Navigator's report:

Sunrise, 6AM, September 29

- Navigator's report: Sunrise: A gray dawn breaks to reveal squalls all around the horizon and Hokule'a hove to under bare masts. It's cold and damp, but the wind is clocking around to the west, a sign that the front may be passing us, moving to the east. The crew waits for the weather to reveal its intentions. For the last few days, Ake Ake have been following in our wake - for company we imagine. Their long slender black wings droop down from their sleek bodies and, halfway to the tip, sweep back like those of supersonic jet aircraft. The birds whirl on the axis of their wings, swooping into the troughs of waves and rising over crests on a cushion of air to roll and swoop again, like a snow skier playing the moguls. This is the eighth day of our journey, and so far we have experienced continuous strong winds and heavy seas. "This voyage will test you," Nainoa warned us a few days before departing, "it will test you physically, mentally and spiritually." By 4:40 a.m. HST Hokule'a opens her sails and, under clearing skies with the wind veering around to the southwest, continues her voyage east - toward Rapa Nui. We expected the southeast trade winds that blow steadily in this part of the Pacific to be yet another challenge, forcing us to tack constantly. But so far we have experienced a kind of miracle - the winds have blown from every direction but southeast. They have been strong from the north, west and south, allowing us to proceed east at speeds sometimes in excess of 7 knots. If this keeps up, we will be in the vicinity of Rapa Nui within a week. I can't say that we expected this," Nainoa says, "but we knew that at this time of year, low-pressure systems cross from west to east, bringing favorable wind shifts for a while. We hoped we might ride one of these systems toward Rapa Nui." But the lows are not just moving with us, they are forming and dissipating all around us in an unusual pattern - one that seems almost designed to push us east. We have had seven days of this miracle wind. Having traveled more than a thousand miles toward our objective, we are jubilant - but silent. We don't talk about our good fortune lest we break the spell. How long can it last? As we continue east we encounter squalls and heavy seas, but the canoe rises easily over the swells, channeling tons of water cleanly between her hulls. She seems alive - responding to the forces of nature as she was designed to, a testament to the wisdom of our ancestors. As I consider the miraculous grace of this wonderful seagoing machine, I reflect back on an event - not so long ago - that almost spelt her doom. Crisis It was in May of 1997. Anticipating the rigors of our voyage, Nainoa hired a marine surveyor to inspect Hokule'a. After so many sea miles, was she still seaworthy? The surveyor laid his hands on the canoe, seeking imperfections in her outer skin. With a penknife, he probed for dry rot, a kind of virus that can reduce wood to dust. He also banged on the hull with a rubber mallet - listening for discordant notes - another sign of problems. Finally, after many hours of poking and banging on that May afternoon, he made his report: "The canoe is rotten," he said. "I cannot certify her seaworthiness. I suggest you think about putting her in a museum." The pronouncement came as a surprise but not a shock. Nainoa had seen places where there was rot and structural damage, but Hokule'a had taken him safely across immense ocean distances and had demonstrated more than her seaworthiness, she had shown her mana, her strength of spirit. Retiring her to a museum was not an option. "OK, I need two lists," Nainoa said to the surveyor, "I need a list of what's wrong and I need a list of what we have to do to make her stronger than when she was built." The list was long and the repairs expensive. But in April, 1998 - after months in dry dock, the expenditure of a hundred thousand dollars, and the gift of more than five thousand donated man and woman hours - Hokule'a took to the sea again. The surveyor returned and qualified her "Lloyds A-One" - signifying her sound in every respect. "This canoe has mana for many reasons," Nainoa once said when talking about this remarkable rebirth, "but one of the most important is the care that so many people have given to her, the literal laying on of hands, thousands of hands, that has given Hokule'a new life time and time again." Thursday, September 30 - The Look Early this morning, after a mid ocean transfer from Kama Hele, I boarded Hokule'a. It was wet everywhere. A gentle rain collected in puddles on deck and ran off the sails. Sunlight descended through a scrim of cloud and rebounded from the steel gray ocean and painted everything silver. Garbed in their Patagonias, the crew looked like monks. They had taken orders. I noticed "the look" immediately. Everyone had it. The skin covering their faces seemed cranked down around the bones, polished smooth. And in their eyes was a gaze I had never seen before. It penetrated and yet was warm and welcoming. The look. Was I too late to discover for myself what it meant? And it was silent. Aboard the escort vessel, the diesel engine throbbed day and night and there was compact disc music in the pilothouse. Here - except for the smooth sound of rushing wind - there was no sound. For a minute or two we regarded each other - the veteran crew and the new arrival. The look. The silence. The silver sheen. A moment that seared deeply into my memory. "Raise the sails," Nainoa ordered. The crew moved to their places - the brailing lines, the bronco, the sheets - and the tanbark sails slipped gracefully away from the masts and filled. Hokule'a began to glide forward and the voyage resumed but now - finally - I was part of it. There were bunks for only twelve so I would share one with Max, Port Six, the furthest forward on the port side. Max - the optimist, the humorist - they had given me a bunkmate with tolerance. "You will be on the six to ten watch," Nainoa said, "so get some rest." I stowed my gear in the puka, a half tent strung from Hokule'a's gunwale to her rail, and squeezed inside. There was the odor of salt water and the rubber sleeping mat and my own sweat. I lay back and watched glistening drops condense on the tent wall and run down under surface tension and gravity toward the bilge. I did not sleep, but I rested, and I thought about "the look." Sunrise, 6AM, October 1 -

Navigator's report: Friday, October 1 - Navigators' meeting Every day at sunrise and sunset, Nainoa, Chad and Bruce gather at Hokule'a's navigator's station to assess their progress in the previous twelve hours. On Friday morning at dawn, the three men look out over an ocean stirred only by gentle undulating swells and ruffled by tiny wind ripples. Cumulus clouds gather on the horizon all around the canoe and, for a time, the sun warms her deck while the crew go about their daily routines of cooking, coiling rope, and writing in their logs. All Navigators' meetings follow a quiet routine. The men analyze the canoe's progress in three time segments defined by watches - the 6 to 10, the 10 to 2, and 2 to 6 - twelve hours between day and night, night and day. "What an awesome night that was," says Nainoa, "I saw Jupiter rise on the horizon, so the atmosphere was really clear. I was able to get a good view of Atria in the south and Ruchbah in the north. The latitude I got from Atria was 25 degrees S, and from Ruchbah I got 26 degrees S." Nainoa also observed Caph and Schedir - which gave him an estimated latitude of 25 degrees S and Navi which produced an estimate of 26 degrees S. "I think we ought to average the observations," he tells the others, "so let's say we are at 25 degrees 30 minutes S." Next, the three navigators average their course and speed during the night. On the 6 to 10 p.m. watch, Hokule'a was beset with light fickle winds caused, they all think, by the fact that Hokule'a passed through a convergence zone between two highs. The sails slapped as the crew tried to find a way to make progress in the light air. Finally, Nainoa decided to close them to prevent chafing. "I don't think we made any progress in that watch," Nainoa says, "but last night was a special time. It gave us all a moment to pause and enjoy this beautiful and special place - the calm seas, the power of the rising moon right at the edge of our earth. Although we weren't going anywhere physically, I think we were all traveling spiritually. Ben Tamura and Mel Paoa stayed up all night, so I know they felt it too. Last night we all enjoyed our special planet and the privilege we have to live on it." The canoe was not only stalled during the 6 to 10 watch but during the others as well. When the three men add up their estimates of miles traveled during the night - factoring the effects of steering various courses as the fickle winds permitted, and the offset effect of wind and currents, they arrive at an estimate of only 6 miles of easting. But this progress was off set, they guess, by a westerly current so the net distance traveled east was only 3 miles. According to their calculations, the distance we must travel east to arrive at Rapa Nui is now 461 miles. "So if this keeps up we'll be in Rapa Nui in 80 days," says Shantell Ching, joking. "Yeah, but factor in the currents, and you get 160 days," says Nainoa. For a moment, the group is silent. The exchange is meant as a joke but there's an edge to it. "O.K. the next critical job is to get down south to the point we will begin our search," Nainoa says. "I estimate that we are about 260 miles west of our search point and 97 miles to the north of it. Soon we've got to transition from longitude changes to making latitude changes." The men consider the problem, assessing the wind and their ability to steer to the south to move from our present latitude of 25 degrees 30 minutes S to 27 degrees 9 minutes S, the latitude of Rapa Nui. "Bruce, let's try and turn down now," Nainoa says. "But check the speed. We don't want to sacrifice speed for direction." As Hokule'a turns from her easterly course to one two houses to the south, heading now Aina Malanai (east-southeast), Bruce watches the ocean flow past the canoe's hulls. Two knots, he estimates. "O.K., let's keep that heading," says Nainoa. At about 7:00 a.m. local time Tava Taupu takes the tiller and begins steering a course to the right of the silver path made by the rising sun. Hokule'a moves deliberately toward her rendezvous with an invisible point in the ocean the place where she will begin the most difficult part of her journey - the search for a tiny speck of land in a vast sea. Looking out over an ocean now speckled with sun glint, Nainoa says, "last night was a turning point for me navigationally. Before, I was so focused on getting east that I did not have a clear picture of Rapa Nui. But now I can see the island in my mind. I'm not saying we'll find it - but that's the first step - to see it." Sunset, 6PM, October 1 - The Search Strategy

Rapa Nui is only 2000 feet high, so a navigator, staring out from the deck of a canoe low to the ocean, cannot see the island until it is only 30 miles away. This "distance of sighting" determines the angle of each zig and zag in Nainoa's course. If the angle is too wide, the crew will not be able to spot the island and the canoe may sail past it and into the empty ocean beyond. The next landfall is Chile, 2000 miles distant. If it is too narrow, it will dangerously increase the sailing time to Rapa Nui, perhaps pushing navigator and crew beyond their limits of endurance. The Search Strategy Explained - Nainoa "Rapa Nui is smaller

than the Hawaiian Island of Ni'ihau and only a little higher. It would

be unreasonable to expect that we could, even with favorable winds,

navigate without instruments 1150 miles from Pitcairn directly to Rapa

Nui. Our traditional system of Original Plan "Before Leaving Hawai'i, based on the winds we expected to encounter during the voyage, we established what we call a 'box' of ocean for the search which begins 300 miles to the west of Rapa Nui, between 25 degrees S and 29 degrees S. Rapa Nui is centered between the northern and southern limits of the eastern end of the box . Targeting this box of ocean - 300 miles long and 240 miles wide, 72,000 square miles in all - rather than a small island 13 miles long and 10 miles wide, 64 square miles, allows us to compensate for any mistakes in our dead reckoning or in determining our latitude. When we reach the western end of the box , 300 miles west of Rapa Nui, we assume that the island is somewhere in this box to the east. So we will sail Haka Ko'olau (N by E) up to 25 degrees S, then Haka Malanai (S by E) down to 29 degrees S, then up north again and so on, in a zigzaging pattern, slowly moving eastward through the box . At some point in this zigzag pattern, we should pass within 30 miles of the Rapa Nui and be able to see it. Modification of the Original Plan "The incredibly good winds we've experienced now allows us to modify the strategy. Because we've been able to sail directly toward our destination in less time than we had originally planned, which reduces the errors in our dead reckoning, we will now begin our search 200 miles instead of 300 miles to the west of Rapa Nui. This decreases the area we have to search by a third, from 72,000 square miles to 48,000 square miles, and will save some time in tacking in search of the island. Contingency Plan To accomplish our search pattern we need favorable winds. To tack north and south we need either easterly or westerly winds. Northerly winds will not allow us to tack north, and southerly winds will not allow us to tack south. But so far the winds have been mainly northerly, so if this continues we will be unable to tack north. If that happens we'll try to obtain a good reading of our latitude stars at night and then sail directly east toward Rapa Nui on the latitude of the island, 27 degrees 09' S. This strategy requires precision in determining latitude. Because the island is so small, we must be within half a degree of latitude or less than 30 miles off for it to work. If, after a period of time, we have not found the island by sailing east we may decide that we've sailed past it and we'll turn around to search back to the west. We have placed a time limit of 30 days on our voyage. We left Mangareva on September 21st so we are now giving ourselves until October 21st to find the island. We have 42 days of food and water on board, however, so conceivably we could stay at sea until the end of October. The Moon We planned the voyage to take advantage of a full moon which will appear on October 24th, but favorable winds and our quick passage toward Rapa Nui has thrown our timetable off. Now we may be searching for the island under a waning moon which will make it difficult to see at night. The moon will disappear on October 8th or 9th and, except for the stars and planets, the night sky will be completely dark. So during our search we plan to stop sailing at night, closing our sails two hours after sunset and opening them again two hours before sunrise. We cannot sail more than fifteen miles in two hours so we won't sail past the island in the darkness. Without moonlight it will also be difficult to determine latitude because our estimates depend on measuring the height of stars above the horizon as they cross the meridian. When the night is dark, the horizon is hard to see.