Sandy Low

"Maybe "charisma" isn't quite the right descriptive word, but there was an unforgettable quality about Sandy. He loved people and his hospitality, unfailing backed by Ginny's patience (Virginia Low, Sandy's wife) and cooperation, was non-stop. No one who enjoyed his shad bakes or chowder parties will ever forget them.

He was unquestionably the most important driving force in lifting the New Britain Museum out of the doldrums. Here is just one example (to which I was a witness) of his extraordinary ability to communicate his enthusiasm for American painting.

Mr. Alix Stanley, retired Chairman of Stanley Works, was a lonely widower with no particular aim in life. In less than one half hour, never having met him before, Sandy aroused his interest to such a pitch that he purchased several paintings on the spot, embraced collecting American paintings for the museum as his full time goal, and gave the first large wing to the museum.

The group of enthusiastic donors and workers for the Museum in general who Sandy gathered around him genuinely had fun in the process. An excuse to work with him was all any of them wanted in recompense. He was a remarkable man."

Robert C. Vose Jr.

Vose Galleries

Boston

Oak Bluffs Storm

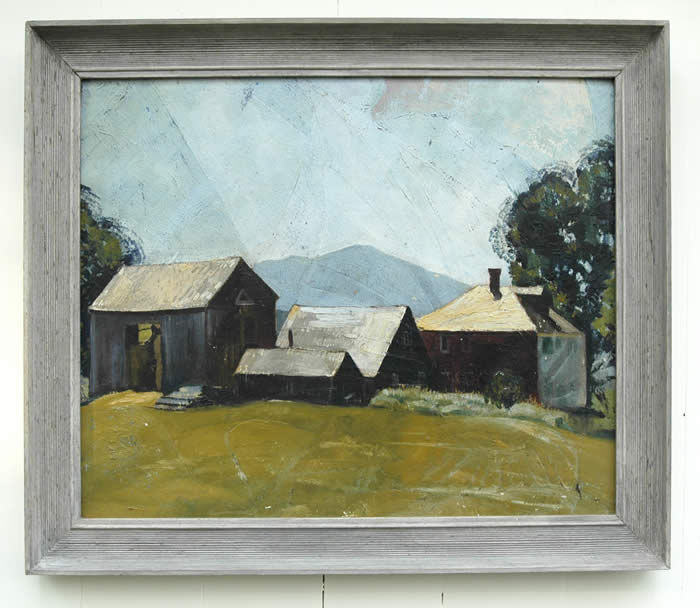

Landscape - may be Woodstock, Vermont

c. 1935

Martha's Vineyard Fancy

1935

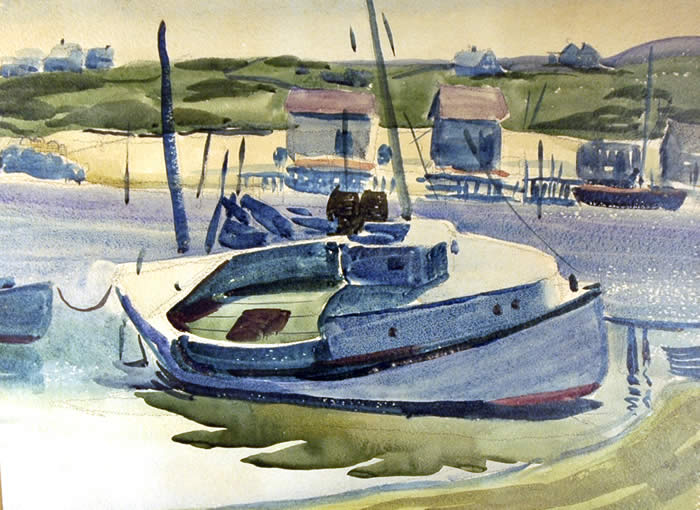

Low Tide c. 1937

(Menemsha)

Black and white photograph (Irving Blomstrann) of watercolor painting

One Way - Village Street c. 1937

(Oak Bluffs Campground)

Black and white photograph (Irving Blomstrann) of water color painting

Menemsha c. 1937

Black and White photograph (Irving Blomstrann) of water color painting

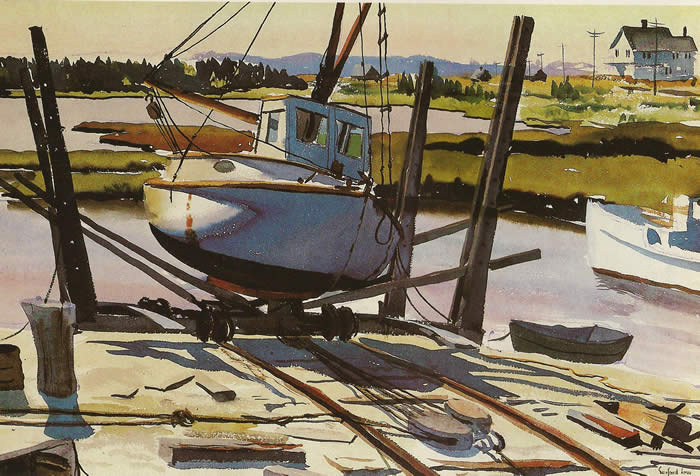

The Boatyard 1946

Upisland House

c. 1960

Early Morning Off Season - Seaview Avenue, Oak Bluffs

c. 1960

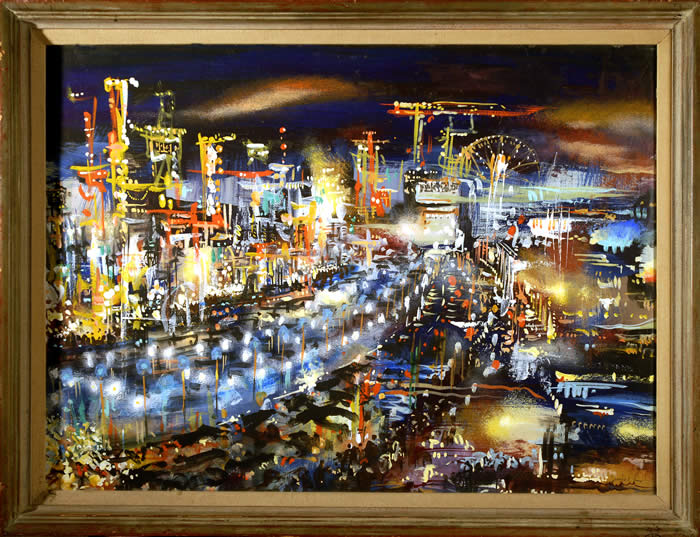

City Lights

c. 1960

Birds

c. 1950

_______________

The Museum School

Sandy attended the famous Museum School in Boston from (about) 1925 to 1927. While there, he founded the school's first football team.

Charles Mahoney, wrote about the team in a memoir of that period: “Sandy was very popular with everyone. He had a warm, infectious smile. In 1925 we organized the first, and maybe the only, art school football team. Sandy was our leader and star. With him, our success was assured. When we graduated there were no more football teams at the Museum School.”

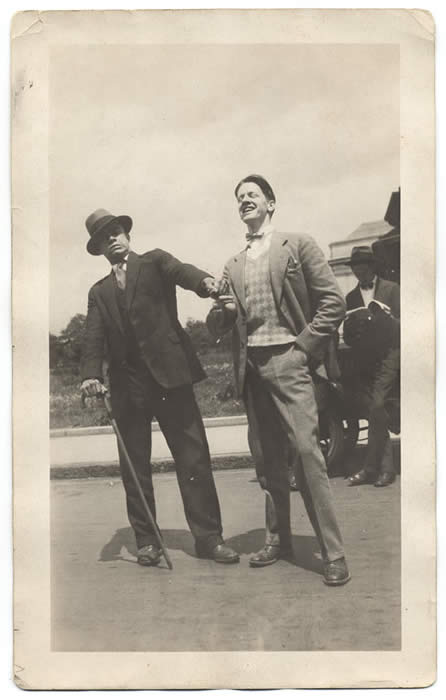

Amazingly, while searching the Smithsonian archive one day, I discovered a series of photographs that Charles took of my father and other classmates at the school. Here they are...

This one is wonderful - it must have been a double exposure. Mahoney (right) and Low (center) seem to be reacting to the ghost image of Happy Horrigan - one of the men they palled round with.

Sandy (right foreground) at the famous Museum School auction where, every year, students sold their work.

Sandy and Happy Horrigan on Museum Road, Boston.

Sandy with Ukulele at the school.

Group Photo of a men's life class at the museum.

Front row: Freeman Garniss, Walter Heffron, Laurence Hobbs, Alphonse Shelton and Vitale Terietsky.

Middle row: Charles Richenberger, (unknown) Brown, Sandy Low, (unknown) Weiss, Harold K. Zimmerman and Samuel Thal

Back row: Elliot Laucks and Benjamin Lanza.

Photo by Charles Mahoney.

In this picture Sandy Low is to the far right. The others, in no order, are Mahoney, Horrigan, Burt Coughlin, Tucker Curry, Elliot Laucks and George Runyon.

But more importantly, my father had found his calling. From a letter to his sister Clorinda Lucas, written on March 17, 1924 when he was 19 he said: “Now here's the point. Without a doubt of any kind, the only thing I'll ever succeed in will be the art line. I've been made for it and I can feel it in me.”

In 1927 Sandy graduated from the Museum School . He went on to New York City where he rented a loft at 21 West 35 th Street . While in New York he studied at the Grand Central School of Art and the Art Student League. He spent four years there as a commercial artist.

(all photogaphs above courtesy of the Smithsonian)

_____

Martha's Vineyard Victorian

(somewhere in Oak Bluffs)

c. 1960

Coal Wharf - Edgartown

Lighthouse - Day's End

c. 1955

Sandy was experimenting with using Pollack's "drip painting" technique in a unique way to create representational (as opposed to abstract) paintings

The Last Flight

1958

Sea Spray

c. 1958

Menemsha

c. 1935

Menemsha Nets

c. 1935

Landscape - probably Kent, Connecticut

c. 1935

Sandy and Ginnie Low painting

by Stephen Dohanos

c. 1959

The Haifa Murals

Sandy Low and Walter Korder painted many murals for various clients. On May 9, 2009, I received the following query from a well known gallery in Old Lyme, Connecticut:

Dear Mr. Low,

Our gallery, the Cooley Gallery has recently acquired and restored an truly stunning mural of Haifa, Israel, painted by your father and his partner, Walter Korder. Given the excellent bio you have written regarding your father's life and work, I was wondering whether perhaps you have heard of the Haifa mural?

With best wishes,

Joe

Joseph F. Newman

Director

The Cooley Gallery

25 Lyme Street

Old Lyme, CT 06371

office: (860) 434-8807

cell: (203) 249-5420

www.cooleygallery.com

After a brief correspondence, the Cooley Gallery sent me the following photographs of the murals and has given permission to include them here:

entire mural

left panel

center panel

right panel

Brief Biography

Sanford Ballard Dole Low was born on September 21, 1905 in Kohala, Hawaii. In 1921, he traveled to attend Loomis School in Windsor, Connecticut where he stayed for a semester, then ran away to sea. In 1923, he was accepted into the Museum School in Boston where he spent four years and organized the school’s first and only football team. In 1927 he went to New York City where he studied at the Grand Central School of Art and the Art Student League and made a living as a commercial artist. In 1930, he married Virginia Hart and moved to New Britain. He started an art school called the Art League. With his colleague, Walter Korder, he painted dozens of murals beginning in 1937 with a series called “The Connecticut Murals.”

Sandy Low was co-founder of the Connecticut Watercolor Society and its President for nine years. He was also President of the Association of Connecticut Artists, an elected member of the Salmagundi Club - the oldest art club in the United States – a member of the American Watercolor Society, the New York Watercolor Club and President of the Connecticut Academy of Fine Arts. One of his paintings was selected to represent Connecticut in the 1939 World’s Fair. Sandy began working in oils, and then became a well known watercolorist. He experimented with acrylics and wood sculpture.

In 1939 he was asked to be a member of the Board of Directors of the New Britain Museum of Art. In the beginning there were only 24 paintings in the collection. Sandy became the museum’s first Director, holding that position until his death in 1964. Under his leadership, the museum became one of the finest small museums in the country, acquiring more than 1500 works of art – many of them recognized today as masterpieces.

Martha’s Vineyard Island, one of Sandy’s favorite places, reminded him of his beloved Hawaiian Islands. He became a consummate fisherman. Every year he gathered a group of artists to paint together for a week. At the end of their stay in Harthaven, the artists displayed their work on the porch of Sandy’s gingerbread house. Most everyone came to drink gin and tonics and old-fashioneds and admire their work.

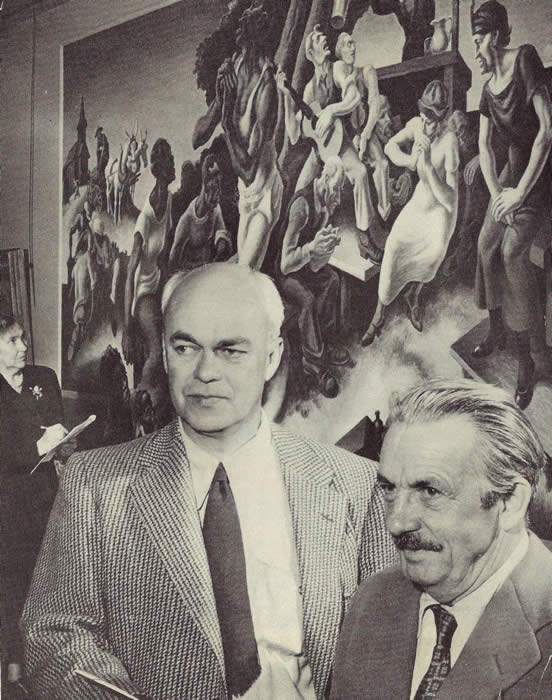

Sandy’s Vineyard connection led to one of the most amazing acquisitions of a work of art by a small museum – or maybe even a large one - the five Benton Murals which were acquired from the famous Whitney Museum in New York in 1954. Tom Benton was a “regionalist” artist. He traveled through our country to put his finger on America’s pulse. He painted life in the raw - dance halls and cowboys, business tycoons and poverty stricken farmers. Today, he is considered one of our country’s greatest artists. Benton and Sandy became fast friends on the Vineyard which led Benton to help Sandy acquire the murals for the New Britain Museum of American Art.

Flora Bentley, Sandy Low, Tom Benton - at the museum in front of one of Benton's murals.

"To be sitting in the company of Sanford Low even for a few hours was like sitting before a glowing fireplace on a chilly evening. One could warm one's soul in the exchange of conversation, humor, and sense of companionship. Even though Sandy has been gone these many years, the warmth remains."

Judith Brown, Editor, New Britain Herald.

Press Clippings

American Idyll

The New Britain Museum offers a stunning spectrum of American artworks - and artful seats from which to contemplate them.

In November, 2010, Art News published a four page article about the museum.

"How did so many important works of art wind up in this collection," writes author Bonnie Barrett Stretch, "and why do major institutions like the Met choose to collaborate with this modest museum in central Connecticut? Answers lie in both its history and current energetic management."

Pointing to the actions taken by Sanford B. D. Low, the museum's first director, she says: "An ebullient personality, Low, throughout the '40s and 50s, courted donors, engaged artists, and seized opportunities to purchase such discoveries as the Benton Murals; Frederick Church's first acknowledged masterpiece, West Rock, New Haven (1849); Winslow Homer;'s Civil War painting Skirmish in the Wilderness (1864); and Childe Hassam's Le Jour du Grand Prix (1867), the first American work to win the gold medal at the Paris Salon."

N. C. Wyeth (1882-1945), Dying Winter, 1934, oil on canvas 42.25 x 46.375", Brandywine River Museum (NEW BRITAIN MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART / December 9, 2008)

Artist As Illustrator: New Britain Museum of American Art Focuses On Drawings Made By Painters

By ROGER CATLIN

The Hartford Courant

December 14, 2008

The New Britain Museum of American Art's first director, Sanford B.D. Low, always had a soft spot in his heart for illustrators. He had been one himself.

So the museum at Walnut Hill Park always kept a eye out for illustrations as well as art, taking in works that magazines were throwing out, or going so far as calling up Norman Rockwell to see if he had anything to donate. (He drove down with "Weighing In" in the back of his station wagon.)

Over the years, the interests of the museum became well known to illustrators, many of whom lived in southwestern Connecticut, a commuter train ride from magazine work in New York City. Thousands of works were donated. Named for the man who headed the museumfrom 1937 to 1964, the Low Illustration Committee of veteran illustrators was formed to help donate and guide the collection.

All of that work culminates with an exhibit that traverses the work of artists who put in time as illustrators over a century.

"Double Lives: American Painters as Illustrators: 1850-1950" begins at a time when artists were in demand by publications as eyewitnesses to news events, doing a kind of visual journalism that would all but be taken over eventually by photographers and video journalists.

Winslow Homer's wood engraving of Civil War scenes preceded the kind of montages that in another century would be replaced by cable news montages with accompanying drums.

Yet in his paintings, such as the 1864 "Skirmish in the Wilderness," he pulls back the focus to the forest surrounding the gunfire in a scene that wouldn't as easily reproduce for magazines.

For many illustrators, drawings for publications helped underwrite fine-art ambitions in the studio. Others, who made money painting scenes for calendars, tried to prove a point by putting a gilded frame on slightly changed versions of the same scenes, where they suddenly passed as art.

Although there wouldn't seem to be such a contrast between illustration and fine art these days, back then some artists worked for magazines only under an assumed name, lest their reputations at the galleries be sullied.

Others agonized over the distinction, such as N.C. Wyeth, whose "One More Step, Mr. Hands" color illustration for "Treasure Island" is one of the museum's most famous works. It's more dynamic than his studio work, such as the one displayed, "Dying Winter" from 1934.

From the 21st century, it's easier to appreciate the art, no matter what its original use. In fact, it's puzzling to think how Seventeen Magazine used Ben Shahn's distinctive illustration "Inside Looking Out" in 1953.

Henry McCarter's pen-and-ink illustration of "The Witch Wife" for Century Magazine in 1911 may be more engaging than his abstract painting "Bells No. 6."

And Gerrit Beneker's painting for a World War I poster may work better than a studio portrait that tried to combine an impressionist background.

It's a trip to find a wonderfully surreal full-page color "Kin-der-Kids" comic from a 1906 Chicago Tribune by Lyonel Feininger years before he'd found the Bauhaus.

But Ben Solowey's haunting portrait of his wife, "Rae Seated (Green Dress)," is something you might not expect from just seeing his quick 1929 sketch of Ethel Barrymore for the New York Times.

And Grant Wood, lured from his geometric paintings of farm landscapes such as "Haying," does some of his most lugubrious work, doing a painting of a film still meant to advertise the John Ford adaptation of Eugene O'Neill's "The Long Voyage Home."

Thomas Hart Benton is a featured artist in the New Britian Museum, so it's no surprise to see him popping up in a portrait of another artist who divided his time between illustration and art, Denys Wortman.

Many of the 50 artists included in the show have long since lost their distinction as merely illustrator or artist. Among them is the glowing work of Maxfield Parrish or the Wild West defining works of Frederic Remington (a Yale grad who lived his final years in Ridgefield).

Organized by the museum and curated by Richard Boyle of Salisbury, an art historian and former director of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, "Double Lives" comes to New Britain after first showing at Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford, Pa., another museum that has historically championed illustrations.

But about half of the works are from the museum's collection, and the Low Illustration Collection, two thirds of which were pulled out of storage to display.

Copyright © 2008, The Hartford Courant

A steadfast devotion to American art

By Jan Shepherd, Globe Correspondent

Boston, Globe

December 21, 2008

NEW BRITAIN, Conn. - In 1903, museums and collectors tended to look to Europe and the Far East for their art, but a central Connecticut institute received a $20,000 gift with instructions to buy only American "modern oil paintings."

That became the seed money for the country's first museum devoted to American art. The New Britain Museum of American Art today counts more than 5,000 paintings, prints, drawings, photographs, and sculptures from the 18th century to the present in its permanent collection.

With 400 of its works on display at any time, the museum also presents traveling and collaborative shows of its holdings.

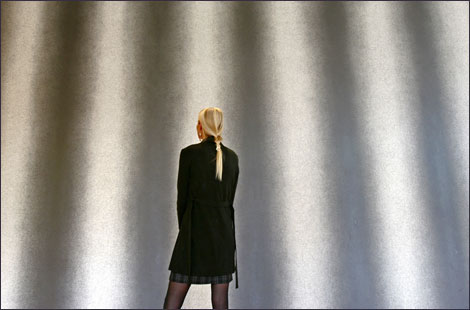

Here, art is everywhere. The LeWitt Staircase showcases Lisa Hoke's "The Gravity of Color," an installation with 20,000 plastic and paper cups attached to the wall and ceilings. The colorful array almost outshines a recently purchased chandelier by glass artist Dale Chihuly.

Upstairs, the New/Now Gallery changes about every three months with solo shows by the up-and-coming. "The Eye Deceived: Paintings by Michael Theise," a body of work executed in the the trompe l'oeil style, is up through Jan. 4. In another gallery, "The Life of Terror and Tragedy: September 11, 2001," Graydon Parrish's huge painting, 8 feet tall by 18 feet long, dominates one wall. A family who lost a member in the World Trade Center attack and the museum commissioned the work.

The museum's profile and ability to show off its rich collection took a giant leap forward two years ago when the 43,000-square-foot Chase Family Building opened. The handsome stone-and-glass, two-story wing added a dozen galleries, a store, cafe, auditorium, and courtyards to the museum, located 9 miles southwest of Hartford.

As part of the $26 million project, the adjacent Landers House, the museum's home since 1937, was renovated for art studios, a library, and offices. With walls of windows, the museum capitalizes on its setting on the edge of Walnut Hill Park, a creation of landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted.

A transparent corridor links the Chase and Landers. For first-time visitors, a free audio guide featuring Douglas Hyland, the museum director, is invaluable.

If time is limited, don't miss Thomas Hart Benton's "The Arts of Life in America," a 1932 mural commissioned by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. The museum purchased the mural in 1953 for $500 after the Whitney decided it no longer wanted it.

An important exhibit through Feb. 22 draws on the museum's renowned Sanford B.D. Low Memorial Illustration Collection. In collaboration with the Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford, Pa., guest curator Richard Boyle and the museum focus on 50 works for "Double Lives: American Painters as Illustrators, 1850-1950," featuring the works of such artists as Winslow Homer, Frederic Remington, and Childe Hassam.

Even fashion finds a place here. Through Feb. 3, "Judith Leiber Handbags" features original, handcrafted purses from private collections.

Jan Shepherd can be reached at jshep@earthlink.net.

New Britain museum enters new era

By Patricia Harris and David Lyon

Boston Globe

December 17, 2006

NEW BRITAIN, Conn. -- In the annals of American art collecting, the acquisition of Thomas Hart Benton's "Arts of Life in America" by the New Britain Museum of American Art may be one of the best deals a small museum ever made.

The Whitney Museum paid $4,000 to commission the five-panel series for its library in 1932, but changed its collecting priorities radically after the death of founder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney a decade later. In 1953, New Britain snatched up the Benton murals for the bargain price of $500.

The New Britain museum started collecting seriously in the first decade of the 20th century, when a single patron donated $25,000 in gold bonds to fund the purchase of "modern art." The museum narrowed its focus to contemporary American work, becoming the first art museum in the country to do so. No doubt John Butler Talcott, the railroad tycoon who made that initial donation, would have been pleased by the astute purchase of the Bentons.

Earlier this year, the museum, which had been housed in a turn-of-the-20th -century stone mansion since the 1930s, opened an airy new building. The 43,000-square-foot structure, designed by Ann Beha Architects of Boston (architects of the Mary Baker Eddy Library ), houses 10 galleries on two floors flooded with light. With the move, the museum has doubled the number of items on view from its 5,000-object collection.

As might be expected for a museum that started acquiring work just before World War I, it has strong holdings in 20th-century art, ranging from bravura landscapes and character studies by N.C. Wyeth to the überrealism of Chuck Close. But the museum also owns earlier works, so it's possible on one side of a gallery to study the spare likenesses by Gilbert Stuart and on the other side, the lush portraits by John Singer Sargent.

One gallery was designed specifically for Benton's set of four murals and a satirical lunette that he completed in six months. The three main panels are devoted to Arts of the South, Arts of the City, and Arts of the West. Benton traveled the country, sketched portraits of Americans in their daily pursuits, and later constructed shadowbox models to work out the compositions.

The murals elaborate Benton's style of sinewy elongated figures, their musculature and chiseled facial features exaggerated by side-lighting and their sheer vigor made vibrant with saturated colors. Although he continued painting into his 80s, Benton (1889-1975) is best remembered for his public murals for the Depression-era Works Projects Administration . Fortunately, "Arts of Life in America" was painted with oils and tempera on linen panels, not directly onto masonry. The murals have stood the test of time to become a classic in the American vernacular style of painting.

In 1959, Benton wrote to museum director Sanford B.D. Low, "The New Britain Museum is my favorite museum. . . . When other museums were getting rid of these, the New Britain Museum was supporting them -- buying them and hanging them on its walls."

But he wasn't the only artist enamored of the small institution. One wall of the new building's lobby is covered with a post modern Sol LeWitt mural titled "Wall Drawing #1196 (Scribbles)."

"It was a gift from the artist," says Paula Bender, the museum's manager of communications and marketing. "LeWitt grew up in New Britain and graduated from New Britain High School. He had his first exhibit as a professional artist in our museum."

Contact Cambridge-based writers Patricia Harris and David Lyon at harris.lyon@verizon.net.

Scott LeWitt's 13x27' foot mural, "Wall Drawing #1196, Scribbles," hangs in the lobby of New Britain Museum of American Art. Boston Globe, August 28, 2007.

The vibrant art scene in New Britain, Conn. makes it a great place to stop by in the winter months. An American art museum, two repertory theaters and a new performing space in an old church have transformed the scene in this city. Pictured is "Lunasa," an oak and cherry sculpture outside the New Britain Museum of American Art.

(Wendy Maeda / Globe Staff) Boston Globe, August 28, 2007.

Children's book art getting big

By Stephanie Reitz, Associated Press Writer

March 3, 2008

AMHERST, Mass. --They're not the "Mona Lisa" or "Whistler's Mother," but images such as the Cat in the Hat, the Very Hungry Caterpillar and other icons of illustrated children's books are gaining respect in highbrow art circles.

Once seen as fun but forgettable, the genre is now being featured in mainstream museums and dissected in college art courses.

And as respect for children's book art grows, the money follows. Buyers are purchasing the illustrations as investments and philanthropists are stepping up, as in the case of the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, which recently received a $1 million gift, its largest donation since it opened in 2002.

Some experts say the reason is simple: More art lovers are recognizing that whimsy and significance aren't mutually exclusive.

"It's undervalued as an art form. The great children's book artists are drawing from art history and the trends of their times," said H. Nichols B. Clark, director of the Carle Museum, which features numerous artists and houses pieces from Carle's decades-long career, including his signature Hungry Caterpillar.

"What is especially wonderful about these illustrations is that in this art form, the playing field is leveled. Sometimes the child has more to say about the image than the adult," he said.

Money can be a touchy subject among art enthusiasts, some of whom question whether inspiration can be tarnished by commercialization.

But some experts say a sure sign of a genre's acceptance is when museums, collectors and philanthropists willingly open their wallets for it, which is increasingly the case with picture book art.

"You can quibble about the critical side of the art, but the market is bearing out that yes, original children's book artwork is getting out there," said Timothy Young, an author on the topic and curator of Yale University's Betsy Beinecke Shirley Collection of American Children's Literature.

Illustrated children's books have long filled the bookshelves of American homes, ranging from Dorothy Kunhardt's simple "Pat the Bunny" touch-and-feel books to the "wild things" of Maurice Sendak's imagination or Leo Lionni's fanciful "Alexander and the Wind-Up Mouse."

The advent of modernism in the early 1900s caused some to started viewing picture book illustrations as moneymaking frivolity, not serious art that could stir the soul. Art that was realistic became viewed as less important, Clark said.

Yet even as they were excluded from the mainstream, children's book illustrators often embraced the same trends as other artists, from art deco to surrealism to Warhol-style pop art.

"These artists were in touch with their peers and influenced by them, even if person 'A' was doing kids' books and person 'B' was doing adult stuff," said Young, the Yale curator. "You can often see the common influences if you compare pieces from the same period."

The book illustrations also often reflected social changes, adding cultural significance to the art.

Ezra Jack Keats' 1962 book, "A Snowy Day," for example, was among the first mainstream children's books to feature black characters -- not coincidentally, in the midst of a critical time in the civil rights movement.

Renewed respect for children's book illustrations started appearing in the early 1980s, led by Japanese museums that displayed the pieces on par with raku pottery, traditional calligraphy and other undisputedly important art forms. The past decade has seen a burst of U.S. museum displays and the growth of facilities to preserve and show it, including the Carle's establishment in Amherst.

Many say the art will have long-term appeal because it crosses generations, introducing children to art and museums while sparking warm memories for adults.

Simon Keochakian, 72, an art collector and psychologist trained in art therapy, said even with his background in the field, he was unprepared to accept picture book illustrations as serious art before visiting the Carle.

"I thought they were talking about comics, something light and simple," said Keochakian, keeping an eye on granddaughters Selma and Hannah nearby after a recent story-time gathering at the museum.

"As I learned more about it, I realized it's an entire genre. I think people are starting to understand that children's picture book art can be very profound, not just a fun distraction."

Some mainstream art museums throughout the United States have purchased pieces, but many put on displays with items borrowed from specialty museums such as the Carle or the Mazza Museum of International Art from Picture Books in Findlay, Ohio.

Washington's Tacoma Art Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago and Connecticut's New Britain Museum of American Art -- one of the first to collect picture book pieces as fine art -- all have displayed exhibits.

"I can't say we're viewing it quite the way we're viewing Monets, but I do think there's been more attention and focus on this," said Jean Sousa, the Art Institute of Chicago's director of interpretive exhibits and family programs. "It's a distinct entity. It doesn't have to compete with the Monets of the world because it has its own special value as art."

The appeal of some images has lasted over the decades, such as H.A. Rey's "Curious George" and Beatrix Potter's "Peter Rabbit."

But art historians and educators say only time will tell which of today's illustrations become tomorrow's icons. From Caillou to Captain Underpants to Lilly's Purple Plastic Purse, the staying power has yet to be seen.

"I think some of it depends on how much they're picked up in different media and how much they're collected over the years," said Rutgers University professor emeritus Kay Vandergrift, who taught courses on the subject.

"There are some that are likely to be around forever, but we just can't predict yet which ones they'll be," she said.