Yassi Ada Turkey

a Byzantine ship wreck

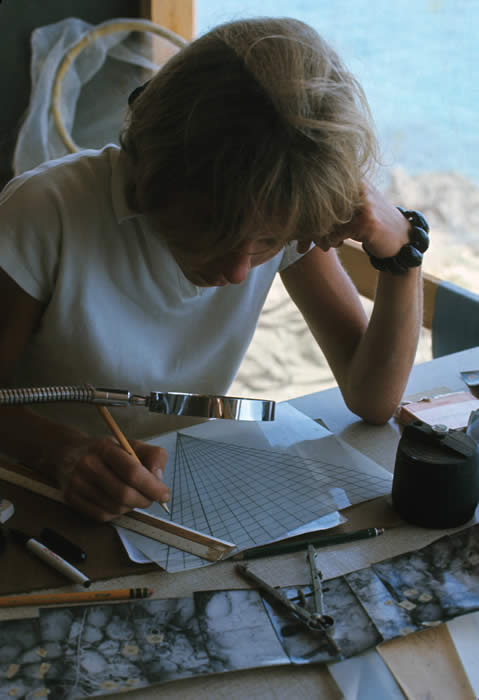

Each piece of wood of the ship's hull is tagged, drawn and photographed for later reconstruction

Institute of Nautical Archeology Photo

In the seventh century AD, about 626, a ship carrying general cargo struck a reef of Yassi Ada Island and sank. The ship carried nearly a thousand amphoras and was discovered by a Turkish diver named Kemal Aras. In 1958, while researching his book - The Lost Ships - American journalist Peter Throckmorton was shown the vessel.

"We found the area of the cabin-galley," Peter reported, " clearly distinguishable because of roof tiles and different types of pottery scattered in a ten-foot area. We brought up samples of every kind of pottery we found: bowls, small jars, and the two types of jars in the main cargo. We were very careful not to disturb the galley area or to dig too deep, because this was a shipwreck of a period never before investigated, the time of the beginning of the Byzantine Empire."

Diver jumping off barge anchored over the ship wreck.

Sam Low photo

We camped on the island in tents

Sam Low Photo

In subsequent years, the wreck was excavated by a team of archeologists from The University of Pennsylvania and The Institute of Nautical Archeology under the leadership of Dr. George Bass.

I was privileged to dive on the ship in 1967 and 1968 with Dr. Bass and his team and to make a PBS film about her in 1980 called The Ancient Mariners. The following is from the film's study guide, written by Dr. Bass:

What would the map look like if Columbus had not sailed for the Indies? How would we live today if oil could not circle the globe in supertankers? People have been venturing across open water for at least thirty thousand years, and seafaring has shaped the world as we know it.The evolution of seafaring is a special interest of nautical archaeologists, who examine what is left of ancient ships, harbors, and ports. When a ship sinks, it carries within it evidence of the crew who sailed it, the trade it was plying, and the way the shipwrights worked who built it. Excavation of a sunken ship thus contributes to our knowledge of bygone civilizations - their societies, their arts, their politics, and especially their economies, for ships have played a major role in trade. It has always been cheaper to move heavy or bulky cargoes over water than over land. It cost less to ship a load of grain from one end of the Roman Empire to the other by sea than to haul it only seventy-five miles by cart.By excavating a seventh-century A.D. shipwreck off the coast of Yassi Ada, Turkey, I and many of my colleagues were able to expand our knowledge about the economics of Byzantine seafaring. Though only 10 percent of the ship’s wooden hull was preserved -the rest having been devoured by shipworms - enough was left for Frederick van Doorninck to reconstruct the ship on paper and for Richard Steffy subsequently to construct scale models. These reconstructions and the hundreds of artifacts found with the wreck-including personal possessions of the ship’s crew and the cargo of over nine hundred large amphoras or two-handled jars-have involved dozens of archaeologists and students in fifteen years of analysis in preparation for publication. Together with historical documents and knowledge about the period gained by other scientists and historians, our analysis produces a vivid picture of one ship’s life from the day its keel was first laid to its last voyage.We know that the merchant ordered his ship built small. Capable of carrying only sixty tons of cargo, it was tiny compared to the great freighters found in state merchant fleets of the past. Like many independent ship-owners, whose numbers increased in the seventh-century Byzantine Empire, the merchant could not afford a larger vessel.The seventh-century shipwrights did not, as we would today, first build a complete skeleton by adding frames to the keel, then cover the frames with planking. Neither did they follow the practice, customary in earlier centuries, of first building the hull by fastening its planks edge-to-edge with a series of mortise-and-tenon joints and then adding the frames. Seventh-century construction fell some-where between these two methods. It continued a trend, starting two or three centuries earlier, that reflected improved technology and also cut down the investment in labor and wood required to build hulls in the earlier Greco-Roman style - perhaps another indication of the modest amounts private entrepreneurs could invest in shipping.

Launching the SDC - submersible decompression chamber

A submersible decompression chamber is provided so that divers,

after working in 130 feet of water, can decompress in comfort at 33 feet.

The chamber also provided for an extra measure of safety.

Sam Low Photo

Even before our excavations, archaeologist’s knew from the Rhodian sea law, a seventh-century maritime code, who the various members of a contemporary crew might be - captain, helmsman, prow officer, carpenter, boatswain, sailors, and the poorly paid para-scharetes (literally, “the one by the grill”) -and each one’s legal share of the profits from a successful voyage. We know that the captain of the Yassi Ada ship was named George because a steelyard or scale uncovered during excavation is inscribed with his name. Since the scale is an item of merchant’s equipment, George may also have been the ship’s owner and a merchant-venturer as well as captain.The rest of the crew is anonymous, but we have evidence that several others were aboard. Accurate plans of the ship’s fragmentary remains show where the helmsman stood to man a pair of great steering oars. The carpenter’s tool chest, stored in a locker between the ship’s cargo hold and the galley or cooking area near the stern, carried everything (except the wood) needed to build an entirely new ship. The boatswain stored his iron foraging tools for shore parties, with a small anchor for the ship’s boat, in a locker at the very stern of the ship. The prow officer may have had charge of the eleven large iron anchors found near the ship’s prow - one pair ready for use on each side and the other seven stacked forward of the mast. (The anchors and other iron implements had actually rusted away centuries before our excavation began, but we could reconstruct them because marine concretions had formed natural molds of the once-solid objects.)The parascharetes must have been the cook or a ship’s boy, for the remains of an iron grill over a tile firebox were found in the tile-roofed galley, which was crammed with cooking and eating utensils along with a variety of pantry wares. George evidently did not lag behind the fashions of the day: Four of his bowls are the oldest precisely dated examples of Byzantine lead-glazed pottery.We can calculate with some confidence the total investment in the ship and all its stores. The Rhodian sea law indicates that the seventh-century cost of a fully outfitted ship ran about 50 solidi(gold coins) per 6 1/2 tons of capacity. On this basis the cost of building and outfitting the Yassi Ada ship would have been some 460 solidi, a substantial sum in times when a shipyard caulker might earn 18 solidi for a year’s work and less-skilled laborers might receive only 7 or 8.As the Yassi Ada ship was being prepared for her last voyage, a procession of porters would have carried aboard the cargo of nine-hundred-odd amphoras and passed them down through the hatch into the hold. Most of the storage jars were large and globular, but some were smaller and more elongated. The large jars could hold as much as forty liters of liquid, the small large jars held wine; unfortunately, the mud contents of none of the smaller amphoras were sieved at the time of excavation.The cook’s stores would have been loaded at the same time as the cargo. We know that his fresh rations included a basketful of dark, gleaming mussels: Their empty shells, carefully nested within one another, were found amid the wreckage.The captain had placed in the galley certain valuables, including a money purse or two. These held at least fifty-four copper folles(coins worth a small fraction of a solidus) and sixteen small gold pieces; the total value of the coins was just a little more than seven solidi. One sixth-century figure gives five solidi as the cost of a year’s rations for one man; in the years when our ship made its final voyage a loaf of bread cost threefolles. The money we found would have fed a crew of fifteen for a month with something left over, so it seems likely that the contents of the purse or purses were the ship’s victualing money. With port and customs taxes already paid, there would have been no need to risk more cash at sea.The seventy coins enable us today to pinpoint the date of the voyage at 625 or 626 A.D. Six of the coins were too badly preserved to allow identification. Of the remainder only two were minted earlier than the reign of the Emperor Heraclius (610 - 641 A.D.). The latest coin in the group was minted in the sixteenth year of the emperor’s reign, that is, in 625/626 A.D. We may safely assume that the ship last sailed in the same year or quite soon thereafter.

Drawing a plan of the ship using photographs taken on the sea floor

Sam Low Photo

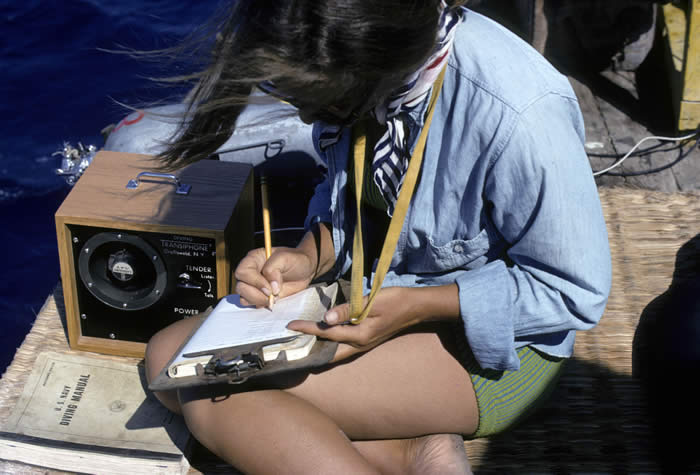

an "underwater telephone booth" was set up on the seabed with a

microphone connected to the surface for communication

with the divers

Sam Low Photo

The ship probably sailed south from the northern Aegean Sea, from the Black Sea, or perhaps from Constantinople (now Istanbul). All but one of the coins were minted north of Yassi Ada, and most of the pottery on board also came from the north. And the ship was almost certainly sailing before the prevailing meltem wind, in a southeasterly direction.The helmsman may have steered a course that would keep him as near the small, flat island of Yassi Ada as he felt was safe. Whitecaps may have camouflaged the breakers over a reef to the west of the island, so that the helmsman did not see danger. As soon as he felt the bottom hit, he must have steered for the island. But the ship foundered in deep water less than a hundred yards offshore. Planing this way and that, like a falling leaf, it silently drifted downward. It landed on an even keel, still pointing toward the island, and then listed to port. We do not know if George and his crew escaped.This story can now be told because of the advancements that have occurred in nautical archaeology over the past twenty years - not only in excavation and safety equipment and methods, but also in the training of archaeologists. To ensure that the new generation of nautical archaeologists is better prepared than were we who pioneered in the field, Michael Katzev and I formed the Institute of Nautical Archaeology, now affiliated with Texas A&M University, and we were later joined by Richard Steffy and Frederick van Doorninck. Students learn to dive and excavate; but first they train to understand and interpret their finds (sometimes while still under water) by concentrating on topics like maritime commerce and naval warfare, the theory and history of wooden ship construction, and the conservation of underwater antiquities. Early in the nineteenth century the geologist Charles Lyell estimated that “a greater number of monuments of the skill and industry of man will in the course of ages be collected together in the bed of the ocean, than will exist at any one time on the surface of the Continents.” Much of this great treasure of knowledge is already lost forever to depths beyond our reach, to decay, or to destruction by looters. But we have only begun to examine what remains, and the coming decades should provide our best look yet at the great human accomplishment of seafaring.

Divers on the way to Yassi Ada in a local small fishing boat

Sam Low Photo

Bringing up wood fragments from the ship's hull.

courtesy Institute of Nautical Archeoelogy

Gear is brought to the island on a fishing boat.

The submersible decompression chamber and land-based decompression chamber

are still on the barge.

Sam Low Photo

Institute of Nautical Archeology Report

During the summers of 1961-64, an expedition of the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania under the direction of George F. Bass excavated the wreck of a 7th-century Byzantine ship that had struck a reef just off the small coastal island of Yassi Ada located between the Turkish mainland and the Greek island of Kos. The wreck lay at an ideal working depth of 32 to 39 m on a moderately steep but fairly even slope and appeared to be well preserved. Then visible was a relatively small amphora mound with a pile of iron anchors at one end and a well-defined area containing kitchen utensils and hearth and roof tiles at the other. (for more information, see the photo galleries)

After an initial season of considerable experimentation with various available mapping techniques, angle-iron frames, measuring 6 by 2 meters and subdivided into three 2-m2 areas, were erected like a series of steps up the slope on which the wreck lay. Each frame, supported by six pipe legs that also helped support the two adjacent frames, could be leveled and set as close to the seabed as possible. This frame system, in conjunction with stereophotogrammetry, yielded a highly accurate three-dimensional plan of the wreck.

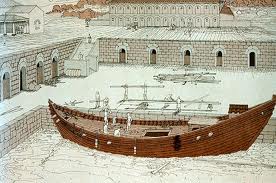

Illustration courtesy Institute of Nautical Archeology

An accurate three-dimensional plan of the wreck site proved indispensable to a reconstruction of the ship. When the ship sank, the keel and hull bottom on the port side had come to rest on a steep slope of exposed bedrock, with the bow pointing upslope toward the island of Yassi Ada. The ship then slid further downslope until the hull's after end began to dig into an area of deep sand. The hull's forward half remained resting on exposed bedrock, and for this reason did not survive. The bottom third of the sternpost, the after third of the keel, and roughly 40% of the after third of the hull bottom on the port side was well protected by sand and did survive. Most of the ship's port side up to deck level between amidships and the stern also survived, due to its breaking off the hull and falling into sand while still fairly intact.

Although it seemed unlikely that enough of the hull remained to permit an overall reconstruction, it was possible to make a reliable reconstruction on paper of the overall shape and dimensions of the hull's after half. The reconstruction would not have been possible had it not been for the fact that a highly accurate three-dimensional plan of the wreck-site seabed had been made that included the impression that the after part of the hull on the port side had made in the sand. J. Richard Steffy, best known for his reconstruction of the 4th-century BC Kyrenia ship, then made a long series of scale models designed to test my own reconstruction and project the after hull lines forward into the bow. In the end, only the shape of the very bow itself remained somewhat in doubt.

Ship model

courtesy Institute of Nautical Archeoelogy

The final model made was a half-model that shows the hull's overall shape and both it exterior and interior construction. (for more information, see the photo gallery) The hull, designed primarily for speed, was notably narrow and streamlined, its maximum breadth being well aft of midships. Although nothing of the rigging survived, we can say that the ship would probably have performed best with a lateen rig. She was rather small, with an overall length of just under 21 m and a capacity of about 60 tons.

The hull had been built in a manner that is transitional between ancient Mediterranean shell construction, in which outer hull planking was fastened together edge to edge by pegged mortise-and-tenon joints, and "modern" skeletal building, in which some frames are erected before planking is begun, and the frames, not the planking, are the primary determiners of hull shape and the primary source of hull strength.

In the ancient Mediterranean world, hulls had been built to last as long as possible, despite the cost. The Yassi Ada hull, on the other hand, was built with construction economies taking precedence over the ship's longevity. Wales girdling the sides of the hull for extra strength and a majority of timbers lining the hull interior were little more than half-logs. Mortise-and tenon joints that edge-joined the hull planking were much smaller and more widely spaced than they had been in earlier periods, and were now unpegged and used only up to the waterline. In earlier periods, frames had been fastened to hull planking by wooden trunnels and long nails driven through the trunnels to the inner face of the frames, where they were clenched. In this hull, planking was fastened to frames only by short nails that barely penetrated halfway into frames.

The ship was carrying 11 anchors when she sank. Seven were compactly stacked on the deck midway between the bow and midships, their shanks laying perpendicular to the vessel's longitudinal axis. Four bower anchors, ready for use, were on the bulwarks close by, two on either side. Three of the bower anchors had each weighed about 250 Byzantine pounds (1 pound=315 gm), or 78.75 kg. The other bower anchor was a best bower weighing about 350 Byzantine pounds (110.25 kg). A complete set of spares with the same weights lay uppermost in the anchor pile on the deck. The bottom three anchors in the pile, each weighing about 450 Byzantine pounds (141.75 kg), were evidently sheet anchors to be used as a last resort in stormy seas.

The anchors have straight arms set perpendicular to the shank. Such cruciform anchors were used in the Mediterranean from the 4th to 10th centuries. The arms at their outer end curve upward and outward, terminating in a spade-like tooth, and near the top of the shank, there is a round aperture for the stock. The bower anchors had wooden stocks when the ship sank, but three iron stocks, stowed with the spare anchors, would have been used when greater anchor weight was desired. Each anchor had been made by hand-forging together at least 20 separate pieces of iron, and the cross-sectional areas of both shanks and arms were kept as small as possible in the interest of making strong welds. Since thin shanks occasionally broke, it was only prudent to carry a full set of spare anchors.

The ship had an exceptionally well-equipped cooking and storage facility located in the stern. This galley complex is of such unusual interest that a full-scale replica of the stern part of the ship has recently been built at the Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology in Turkey so that the modern public can visit the galley in person. (see the photo gallery) Thanks to the fact that the find spot of everything of the galley and its contents to survive was recorded as precisely as possible, the basic location, size, layout and structural features of the galley as reconstructed are firmly supported by archaeological evidence.

The galley floor was set down low within the hull at a level that maximized the amount of space within the galley. A tile firebox with an grill consisting of movable iron bars occupied the port half of the floor. The hearth tiles had been laid in a matrix of clay reinforced by iron bars and probably enclosed by a wooden box. The galley structure rose far enough above the deck to allow for access and adequate lighting. When openings were closed in bad weather, smoke from the hearth could escape through a large circular hole in one of the tiles of the galley roof.

Preparation and cooking utensils, kept in the immediate vicinity of the hearth, included a mortar and pestle, 21 cooking pots in a variety of shapes and sizes, and two cauldrons and a bake pan of copper. (for more information, see the photo gallery) Food containers included at least 16 terra-cotta pantry jars. Also on the starboard side of the galley opposite the hearth stood the ship's water jar. Serving utensils included several copper or bronze pitchers, a glass bottle, 18 ceramic pitchers and jugs, a half-dozen spouted jars with lids, and four or five settings of a fine tableware, each consisting of a redware plate and dish, a glazed bowl and a one-handled cup. A ceramic pipette, or "wine-thief", was used to transfer wine or water from storage jars to pitchers. The coarse ware pitchers, jugs and jars were kept near the hearth and on the galley's after wall, but the more costly tableware and metal vessels were stowed with the food in the main storage locker, which was secured by a padlock. In this locker were also kept coins, weighing equipment, a tool chest and repair materials, spare lamps, and a bronze censer.

Sixteen gold and some 50 copper coins recovered from the wreck had all been kept within the main storage locker, the gold coins in one container and the copper coins in another. All the gold coins except one were issues of the Emperor Heraclius (610-641), and the latest of the copper coins dates to the year 625/626, indicating that the ship probably sank either in or shortly after 626.

The weighing equipment consisted of a large steelyard; two small steelyards, one equipped with a balance pan; a set of silver-inlaid balance-pan weights; and a single glass weight. The large steelyard, with a weighing capacity of about 400 Byzantine pounds (126 kg), whose counterweight takes the form of a bust of the goddess Athena, may be the largest steelyard from antiquity to survive. The balance-pan weights constitute one of the most complete sets of Byzantine weights known.

The ship was well supplied with tools and materials for making necessary repairs during the voyage including axes, adzes, an awl, a bow drill and bits, billhooks (for rough trimming of wood), a carpenter's compass, chisels, files, gouges, hammers, knives, punches, one or more saws, a carpenter's belt for carrying tools, netting needles and spare lead weights for repairing fish nets, and an interesting assortment of lead weights and lures for deepwater line fishing. (for more information, see the photo gallery)

There were at least 16 spare lamps in the locker. Eight others in use were kept near the hearth. The ship's censer, whose open-work lid was surmounted by a cross on an orb, probably was used to sanctify both religious ceremonies and transactional agreements, as well as provide incense at meals.

The ship was carrying approximately 900 amphoras when she sank. Some 700 of these were globular jars with capacities ranging from 10 to some 40 liters; the rest were cylindrical jars with pinched waists that carried from 4.5 to 14.5 liters. The globular amphoras had been stacked three to four deep in the hold, and the cylindrical jars in order to fill the remaining space between the globular jars and the deck beams. had then been placed between the necks of the top layer of globular jars. Only 110 of the amphoras were raised at the time of the excavation.

The amphora interiors were in a majority of cases lined with resin, which prevented low-viscosity liquids from seeping through the walls; we concluded that the amphoras very probably had been carrying wine. About 165 amphora stoppers, terra-cotta disks cut from the walls of amphoras, were recovered from the wreck. In view of the relatively small number of stoppers recovered, we speculated that many of the amphoras might have been empty at the time of the ship’s sinking.

There were graffiti (carved inscriptions), often completely hidden by concretion deposits, on many of the raised amphoras. The graffiti appeared to be of sufficient potential importance to justify the raising of the amphoras still remaining on the seabed at Yassi Ada so that all the amphoras might be cleaned and more closely studied. During the 1980s, 570 additional amphoras were raised; about 140 remain on the seabed.

While a majority of the globular amphoras, which belong to a class known as LRA13, appear to have been made not long before the sinking of the ship, a substantial number are LRA2 jars that had been made as many as several decades earlier. The LRA13 jars had been made with unusual care and dimensional precision. Their mouths reliably accomodated bark stoppers of a standard size; a bark stopper was found still in situ in the mouth of one of these jars. The mouths of the LRA2 and LRA1 jars were made with less precision and had been sealed, we now believe, with the terra-cotta stoppers, one of which remained in situ in the mouth of a LRA1 jar.

The organic contents of still-intact amphoras raised in the 1980s were examined in an effort to determine the nature of the ship's cargo. A recovery on average of just under a dozen grape seeds from intact amphoras indicated a majority of the amphoras had been carrying low-grade wine. However, some of the graffiti revealed that there were LRA13 jars that had in some cases been carrying olive oil and in some cases sweetened olive oil for liturgical purposes. Graffiti on several of the LRA 2 jars indicated that they had once held lentils. Several dozen different marks of ownership occur on the LRA2 jars; some had had more than one owner. Since these jars show few signs of prolonged use, it is likely that many of the older ones had served for some time as sedentary storage jars.

It is extremely unlikely that some kind of commercial activity would have brought together on one ship so many different types of reused amphoras having so many different prior owners and varying so greatly in age. However, historical events taking place during the period when the ship sank give us a quite plausible explanation for the assemblage that does not involve commerce. Between 611 and 628, the Byzantine Empire was engaged in a protracted war with the Persians so devastating and financially costly that it became necessary for the church to lend major assistance to the State, perhaps partly through levies of produce from church-owned lands for the army. Particularly in view of rather frequent allusions to the Christian faith among the graffiti on the amphoras, it seems likely that the ship's cargo of low-grade wine, olive oil, and liturgical oil had been part of this effort. Some of the major types of globular amphoras and many of the lamps on board may have been made somewhere along the coast not too far north of Yassi Ada in the general area Samos and Chios. On Samos, a contemporaneous monastery complex where cylindrical and globular amphoras much like those from the Yassi Ada ship waited to be filled with oil or wine from nearby presses has been cited as archaeological evidence for the church's role in provisioning military bases at this time. The capacities of one of the major subtypes of LRA13 jars, now designated as Yass?ada Type I amphoras, link the jars with the Byzantine annona (civil and military supply) system: 6 annona measures of oil, 114 Byzantine pounds of dry wine, 6 annona measures of dry wine, and 7 annona measures of oil.

We are now inclined to think that the ship, which belonged to the church, had been attached to a military supply fleet based at Samos, may have participated in efforts to supply Constantinople while besieged by the Avars and Persians (626), and had sunk while voyaging to Cilicia with supplies for a Byzantine army then campaigning in eastern Anatolia under the command of the emperor Heraclius.

The end of the war against Persia came in 628 with both sides totally exhausted. The power vacuum made possible the successful Arab invasions in the 630s that were to change the Mediterranean world forever. This historical context and the unusual nature of the ship and its cargo makes the 7th-century Yassi Ada wreck one of the most interesting and important excavated shipwrecks in the Mediterranean.

(Text adapted from van Doorninck, Jr., F.H., "Kirkens skib?-Yassi Adavraget fra 600-tallet," Hvad Middelhavet gemmer [Arhus 1997] 105-120 and augmented by recent research findings.)

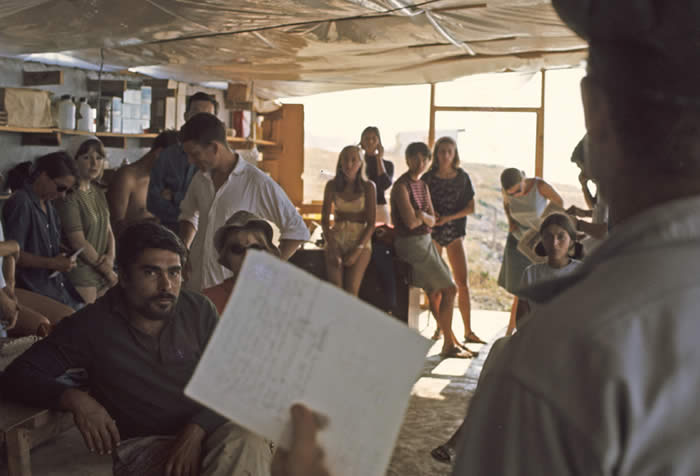

Dr. George Bass briefs the diver-archeologists

Sam Low Photo

The Ancient Mariners

a film by Sam Low

for the Odyssey Series of PBS programs

Cinematographer and director, Werner Bundschuh, filming for the Ancient Mariners in Greece

The Ancient Mariners follows nautical archaeologists as they excavate three shipwrecks in the depths of the Eastern Mediterranean and as they analyze their finds in the laboratory. The three ships, dating from before 300 B.C. to 1025 A.D., tell the story of a significant change in the methods of ship construction - a change reflecting broader alterations in social, economic, and political conditions.

At Serse Liman, Turkey, George Bass, the founder of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA), led an investigation of a ship that sank in 1025 A.D. As we see it before excavation begins, the wreck is barely noticeable on the seabed; but the ship's cargo, mostly broken glass, appears as the archaeologist divers remove silt with an airlift. Showing the huge collection at Bodrum, Turkey, Bass explains that the ship must have been carrying glass for eventual recycling. Fredrick Van Doominck shows the elaborate methods for preserving the fragile pieces of the ship's hull on land. Michael Katzev, also associated with INA, excavated a Greek merchant ship that sank off Kyrenia on Cypress in the fourth century, B.C. The ship carried a cargo of wine in large amphoras. Richard Steffy learns from making a model of the ship that it was built quite differently from the Serce Liman ship. This "hull-first" construction process required not only more labor but a great deal more wood. Lionel Casson tells us that the craftsmanship of the Kyrenia ship was made possible by the use of slave labor, on which Greek society then depended.

George Bass had earlier excavated another shipwreck near Yassi Ada, an island off Turkey, that helps to explain the change in ship construction. The Yassi Ada ship dates from the seventh century A.D. and its construction fell somewhere between hull-first and later frame-first methods.

Film Review

THE NEW YORK TIMES

TV: 'ANCIENT MARINERS'

By RICHARD F. SHEPARD

Published: September 29, 1981

MAN made a road out of the barrier of the sea by building ships, and this most adventurous and ancient pursuit opens the new season of ''Odyssey,'' the series that looks at history and life through the lens of anthropology. ''The Ancient Mariners,'' at 9 o'clock tonight on WNET-TV, achieves a fascination worthy of its topic in sound and picture.

The episode shows how modern scientists have recreated from wreckage found at sea bottom near Greece, Turkey and Cyprus the way ancient shipbuilders built the sturdy craft that carried cargoes. They have also learned about the crews and the civilizations the ships served.

Three antique ships are involved in this program, one from the fourth century B.C., another from A.D. 625 and the third from the 11th century. The scenes shift from underwater sites to the Nautical Archeology Institute at Texas A & M University. From blackened fragments of wood, from thousands of lumpish remains of amphora containers, entire ships and cargoes are reconstructed. Dick Steffy, a marine historian and craftsman, makes models from the evidence and tells how he learns about the thinking of the ancient shipmakers by trying to reproduce their work.

This is more than a program about ships and history; it is a most absorbing account of research process, of forensic investigation, of the scientific mind applied to the humanities. ''Odyssey'' is good at this sort of thing, and this first showing, with Michael Ambrosino as executive producer, Sam Low as producer and Werner Bundschuh as director, gets the season off to a fine start.

To purchase The Ancient Mariners please see: http://www.der.org/films/ancient-mariners.html