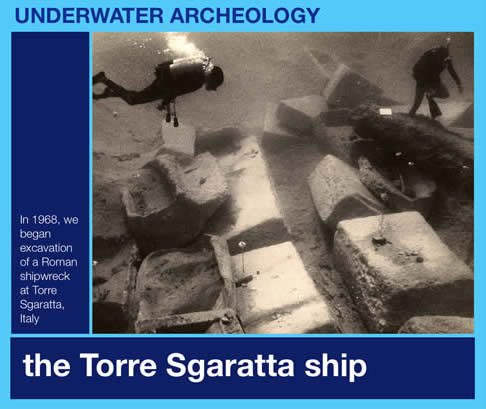

The Torre Sgaratta Shipwreck

Between 1967 and 1968, I joined a National Geographic/University of Pennsylvania archeological expedition to help excavate a Roman shipwreck near the medieval tower - Torre Sgaratta - in southern Italy.

My mentor, Peter Throckmorton, led the expedition. His wife, Joan, was the artist. Terry Vose, a good friend, and Kim Hart, my cousin, joined as diver/archeologists - along with many others..

The Story of the ancient ship

as told by Peter Throckmorton after analysis of artifacts found aboard:

"Like dozens her kind, she loaded her cargo of half-finished sarcophagi and marble blocks on the Turkish coast, perhaps in Miletus . She may have set sail late in the summer, stopping for additional marble at Greek island ports. Rounding the Peloponnesus, she beat northward along the Greek coast, staying in sight of land as long as possible. At last she swung westward across the Ionian Sea to Cape Santa Maria di Leuca at the tip of the heel of Italy. She then set course for Messina. That night the wind must have changed. From the south the dreaded sirocco began to blow. By midnight, his ship laboring heavily, the anxious captain would have put lookouts in the rigging. At dawn they sighted land. With her great square sail, and her heavy load, the ship did not go well to windward. She was trapped in the Gulf of Taranto."

"The captain ordered the anchor out in 15 or 20 fathoms. As the gale increased, the first anchor dragged and the doomed ship inched toward shore. The first anchor and then another were lost as the stout cables broke. In the deepening darkness, the big ship worked inexorably toward the six-fathom line, where the long seas curled to break. The gale shrieked louder. Nothing to do but cast out all remaining anchors and pray, as St. Paul did in like circumstances. If the vessel survived until daylight, there was a chance—just a chance—to run her ashore, accepting the loss of ship but saving the lives of those aboard. It was the captain's last gamble: His ship foundered that night, five hundred yards offshore. The old vessel had given up at last, as old ships must when pushed too hard."

Archangel - the expedition's vessel

Archangel was a Greek Perama especially outfitted for underwater archeological work. Based in Greece, she was sailed to the site near Taranto, italy.

"In the spring of 1967, we sailed Archangel to Piraeus, and the rest of the crew reported for duty. Sanford (Sam) Low, our "executive officer," had just served his tour as a naval reserve lieutenant on a tanker off Viet Nam. Terry Vose from Boston signed on to look after Archangel's primitive engine and our four cantankerous compressors. Sam's cousin, Kim Hart, came along as sailor, photographer. A retired Greek sea captain, a friend of Archangel's former owner, joined us as bosun and man-expedition of-all-work. His name was Manolis. He had gotten tired, he told us, of sitting around the house with the women all day. Captain Manolis and Joan made friends, not a simple thing in the Mediterranean world where it is considered bad form for women to scrub out bilges with lye. It was Joan's proudest day when the Greek skipper trusted her with the blowtorch while he worked along with the scraper, and together they cleaned 20 years of paint from deck and scuppers.

"In the middle of June 1967, we sailed Archangel from Greece to Taranto. When we arrived, we found to our astonishment that most of our diving machinery was in working order and ready to go. Joan, who had been sent ahead in May to prepare for our arrival, modestly explained, 'I told the men my husband would beat me if everything wasn't ready.'"

The wreck

These large chunks of marble are the ship's cargo - partially shaped sarcophagi and columns

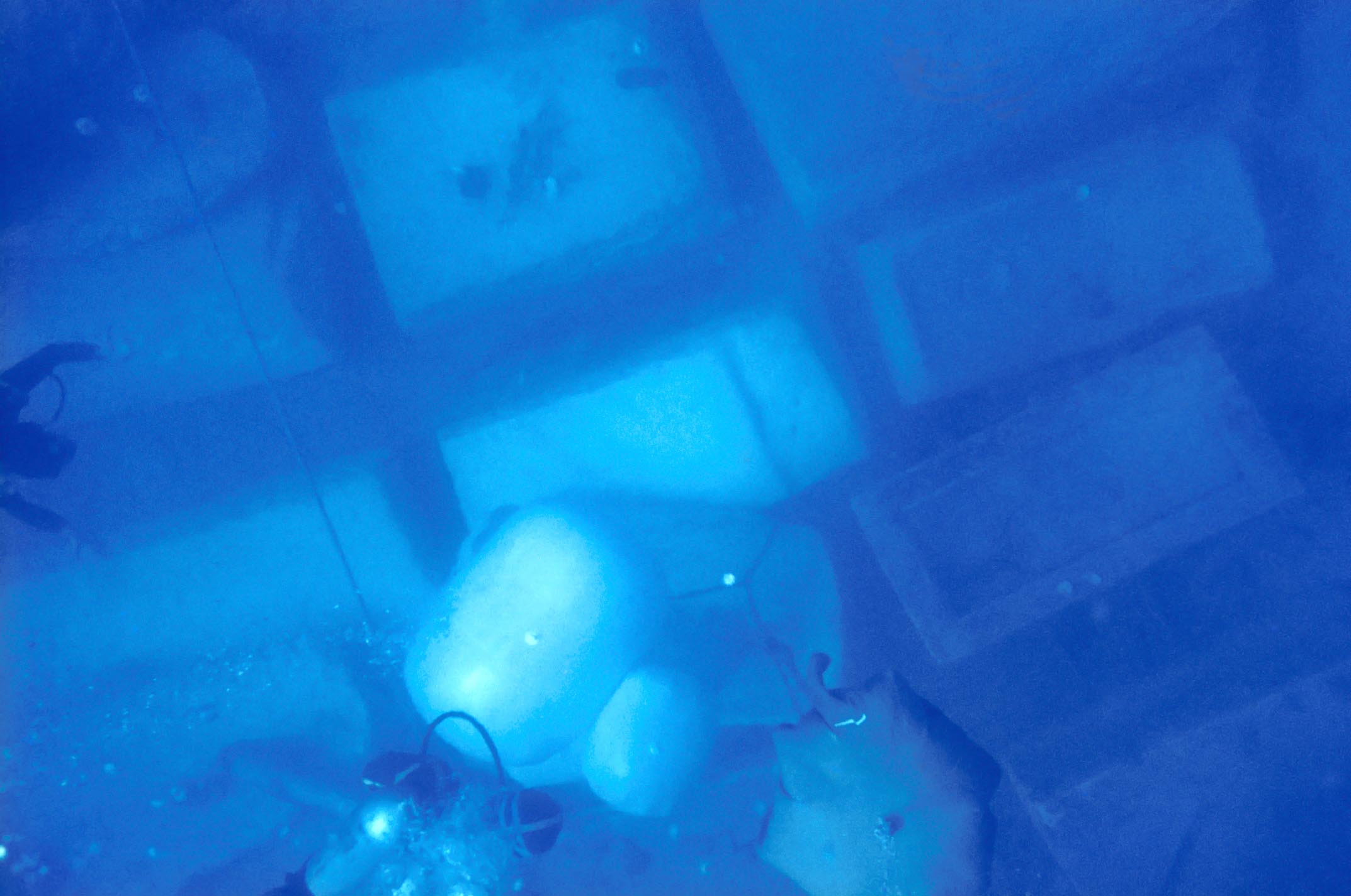

A view of the wreck from above showing dozens of marble sarcophagi - coffins - which were part of the ship's cargo. The diver is filling "lifting bags" with air which will lift one of the coffins off the wreck site so we can explore what is left of the hull of the ship. One of the expedition's goals was to provide data for the study of the evolution of marine architecture - how ancient ships were built.

"We moored Archangel over the wreck and began digging with the air lift. As the great pit on the bottom sank deeper, we kept finding more and more sarcophagi. The sand also held thousands of fragments of the half-inch-thick marble sheeting which had formed part of the ship's cargo. One sarcophagus, fortunately, stored intact seven of these fragile marble panels."

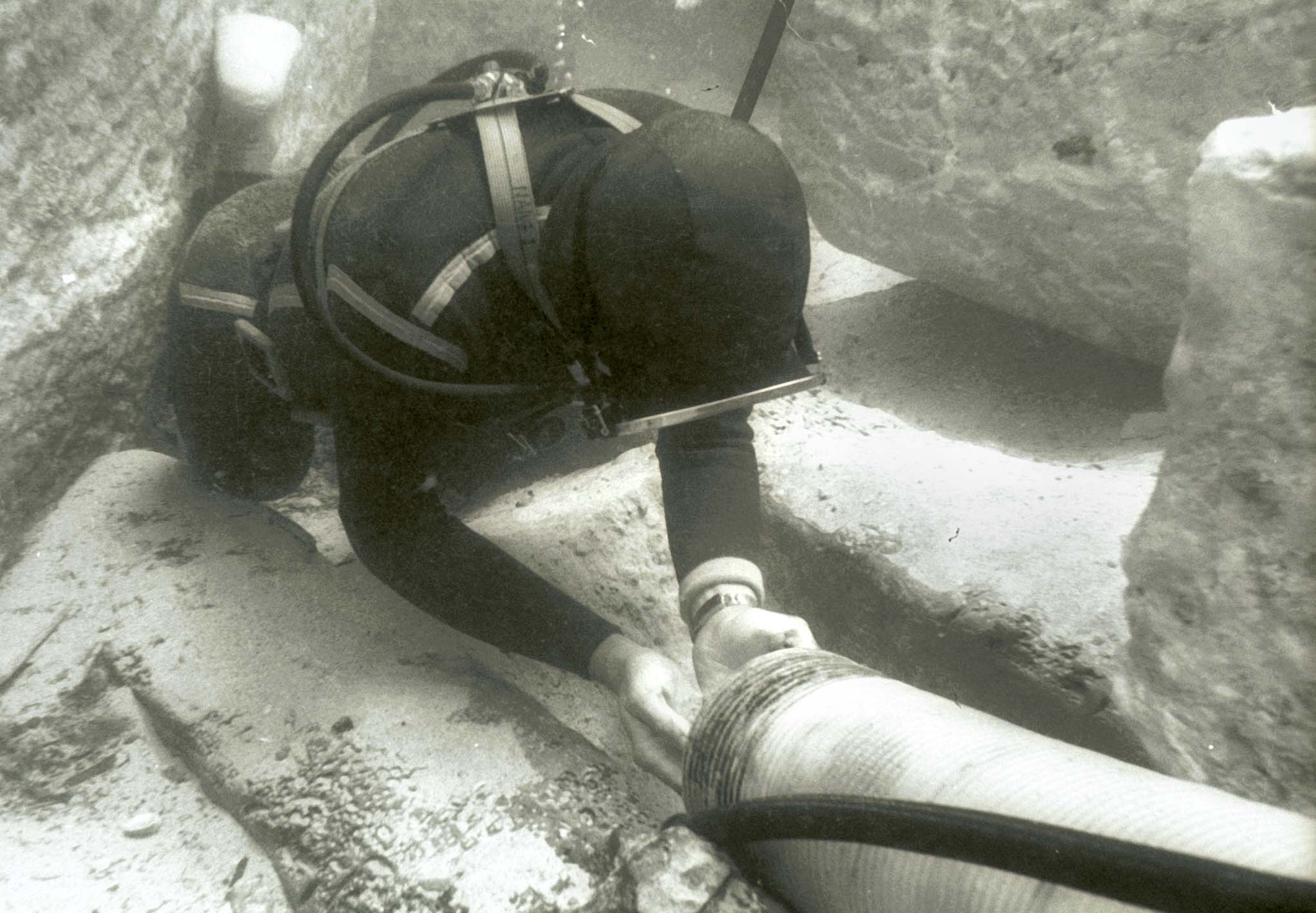

Joan with airlift - pushing back the sand from the wreck. You can clearly see how deeply buried the ancient ship was.

Peter with the airlift - an underwater vacuum cleaner. A bag of marble pieces is in the foreground. He is surrounded by the ship's cargo - marble sarcophagi (coffins) - which were being shipped from Marmaris, Turkey, to Rome when the ship sank.

Excavating in between the sarcophagi by carefully removing handfuls of sand and introducing them into the mouth of the airlift. A piece of wood - part of the hull of the ancient ship is in the foreground.

Peter fills an air bag which will rise to the surface - lifting one of the sarcophagi

"By mid-July we had moved perhaps a thousand tons of sand. Now our air-lift diggers began to uncover a lot of wood pinned under the sarcophagi. Imagine our excitement to find planking. Big pieces of pine were fastened together with oak tenons, construction like that of the third-century B.C. ship Captain Cousteau had excavated at Grand Congloue."

We removed our swim fins when diving on the wreck so as not to stir up sediment or damage delicate pieces of wood with the wash from the fins.

Beneath the cargo of sarcophagi we found pieces of the wooden hull of the ancient ship. Each piece was tagged and drawn in place before being lifted to the surface. Joan Throckmorton uses a sheet of plastic to sketch the wood. Later, she will draw it to scale on a plan of the ship.

Joan measures the wood for later use in making her scale drawing/plan of the ancient ship.

"What a task for our draftsmen! Joan and archeologist-artist Diana Wood made most of the drawings; artist Joe Conroy assisted with measurements which by summer's end totaled 10,000. As each piece was uncovered, they had to draw in every nail and nail hole, every mortise and tenon, every mark on the wood while underwater.

One day Diana watched in fascinated horror as a whole section of hull planking began to ripple slowly up and down. Soon two eyes and four arms appeared at one edge of the section: An octopus was making his home beneath our flimsy ruin.

In many places the planking looked almost freshly cut. The newly uncovered pine shone breathtakingly bright yellow, but darkened in the sea after very few days. The frames were in a much poorer state of preservation, blackened by rot and far more fragile.

We found pieces of hull with characteristics previously known only from ancient mosaics.

One cherished object was the step for the forward-raking foremast that held the artemon, or steering sail.

Digging into the deepest layers of the wreck, we began to find potsherds by the hundreds. They helped us date the ship. Most of the pots seemed to be Imperial Roman, from the end of the second century A.D. or a little later. Definitely not Italian in style, they probably came from Asia Minor. We found pieces of fine plates, bowls, and jugs that may have graced the captain's table, and bits of cooking pots blackened by the galley fire.

The skill of the shipwrights who had built our vessel nearly 2,000 years before stirred our sense of wonder. Unlike modern vessels, ours had no calking between the heavy planks. They had been fastened edge-to-edge with mortises and tenons, and were so well matched that the swelling of the wood in water was enough to make the ship watertight."

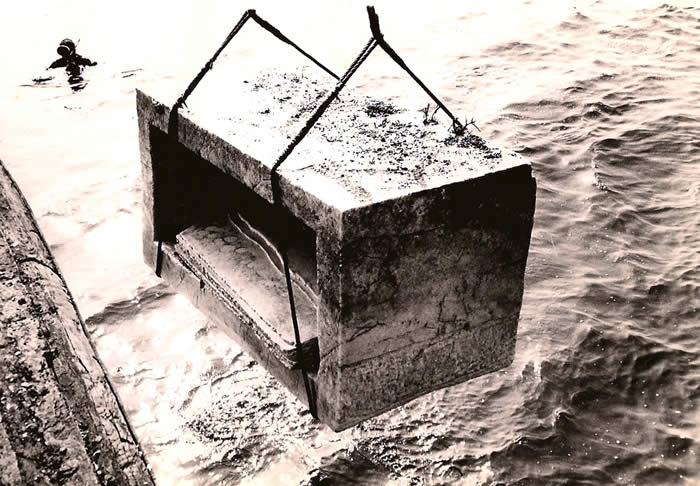

Peter gives the order to a crane mounted on a barge to lift one of the sarcophagus off the wreck.

A few moments later, the sarcophagus emerges from its ocean resting place after almost 2000 years.

________________________________________________________

Sam - four years earlier at the excavation of the sunken Gaeco-Roman city of Kenchreai.

NOT THAT IT WAS ALL WORK....

Kim and one of Joan's sons playing after work.

Sam in ratlines

Sam Diving

HARRY, DANI, MARY, KIM

Back at the tower - after diving....

Report of the Excavation

by Peter Throckmorton

(partial - working on this)

The cargo of the ship consisted of 42 blocks of rough cut stone -18 sarcophagi and 23 blocks, six of which were of alabaster. The sarcophagi had marble sheeting stowed inside them. Most of this sheeting was broken, although one group was recovered intact, and the weight of the cargo was estimated at 160 metric tons.

Surviving ship's wood include several fairly large sections of tenoned hull planking, frames, wales, a mooring bitt, a piece of the keel, and the mast step for the artemon. A wooden mallet of the sort perhaps used by masons was found in good condition.

Six coins were found, all bronze. The best preserved appears to be from Lesbos, a Roman Imperial of the emperor Commodus. This would date the wreck to the end of the second or beginning of the third century A.D.

A considerable amount of pottery was recovered, most of it badly worn and eroded. It consisted of bricks, assumed to be from the cooking fire; roof tiles of at least two distinct types, curved and ridged; large amphoras and storage vessels; cooking pots; and fine ware. Of the large amphoras and storage vessels none are restorable, but they included some very large fragments. At least fourteen separate vessels with an inside coating of resin or some similar substance can be distinguished with certainty, and probably as many more with no inner coating. Most of this category were dark in color, many with a cream or pale slip on the outside. There were a few sherds of red clay, and one distinctive vessel which Dr. Fausto Zevi informs us he has also found at Ostia. Of the fine ware there are fragments of plates, bowls, and Samian type ware, and grooved bowls. None of these appears to be of Italian origin, nor do the large vessels mentioned above, but there are enough characteristic rim profiles and preserved surfaces to make it possible to identify their source. Preliminary work on the fine ware by Dr. William Phelps of the British School in Athens indicates that all the pottery comes from Asia Minor. One group of fragments is well identified as Chanderli Ware, from what is now the Izmir region of Modern Turkey.

A C-14 analysis of the wood, done at the University Museum's Applied Science Center for Archaeology, has given a Radiocarbon date of 79 plus or minus 44 B.C; using the half life value of 5370 years. This is a very reasonable date, considering that the sample came from planking; all the planking was cut from heartwood, which was at least one hundred years old when cut and put into the ship.

The discovery of patches, on the planking, during the 1968 season, confirms the radio carbon dates indication that the ship was old when she sank. These patches were put on with iron nails, unlike all other below water parts of the hull, which was fastened throughout below the waterline with wooden trunnels and copper nails.

Samples of the wood used in various parts of the construction were sent to Mr. B. Francis Kukachka, of the United States Department of Agriculture Forest Products Laboratory in Madison Wisconsin. One of the most interesting identifications was the one made of the packing branches, which served to fill out uneven places in grown frames where they met the inside of the ships planking, and were undoubtedly part of the original construction of the ship. These were Tamarix, which M. Kukachka has seen used as dowels in small Egyptian artifacts.

The ship, judging from the size of the planking, was larger than any ancient seagoing ship found to date: the only comparison is with the planking of the Nemi barges, which was about one third larger. Although the bow and stern had gone, as well as all the ships upper works above deck level, enough survived under the sand so that we will someday, hopefully be able to make a valid partial reconstruction of a large roman ship of a type that has not been previously studied.

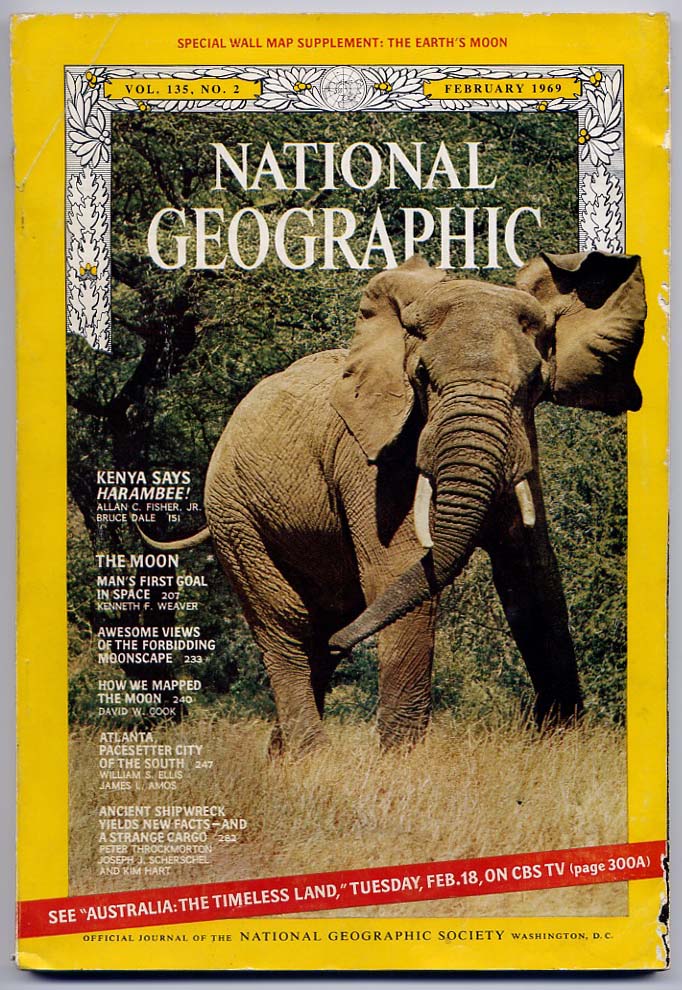

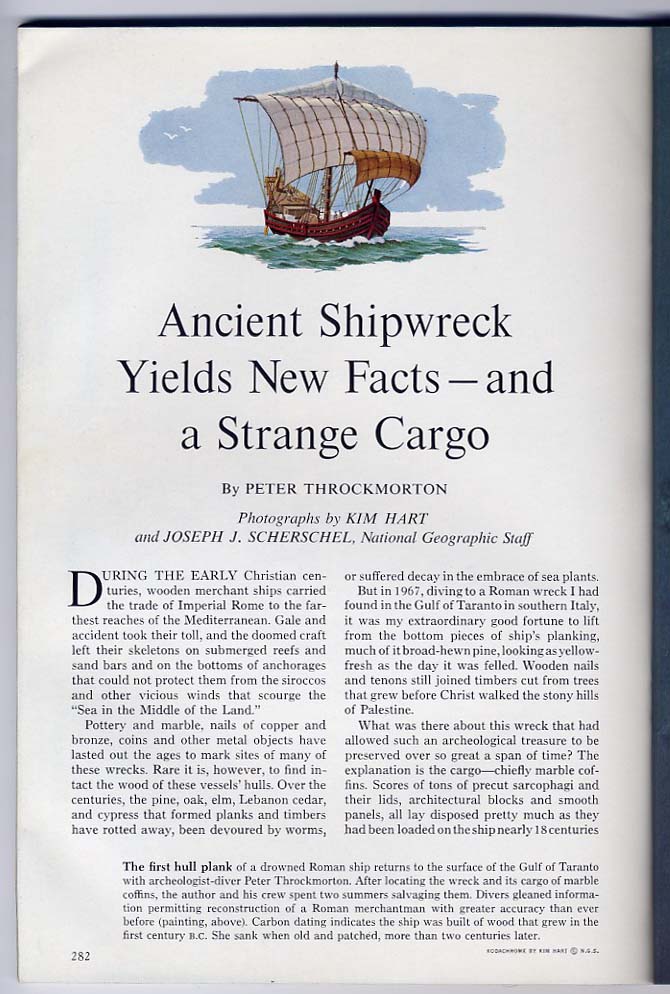

A preliminary, popular, report on the wreck came out in the National Geographic Magazine of February 1969.

The wood of the ship is at present stored in fresh water tanks at Castel San Angelo, in Taranto: The chemical preservative (Topane) that had been added seems to work well enough. The tanks were last visited in 1984, and although tanks have gradually dried out, the wood appears to be slow drying well enough because of the high humidity of the vaults where it is stored.

Planking averaged 72x220 mm and was Pinus Sylvestris. The construction seems to be in a similar tradition to the Nemi Ships. No complete planks were found, but it seems likely that runs of plank were long, well over five meters. The planks were morticed at 35 mm intervals with mortices that penetrated 83 mm. There was no evidence of caulking.

Tennons were live oak 11x 12Ox167mm. attached with 1 mm treenails of Laurus (Nobilis). It was clearly evident that, as at Antikythera, (See Transactions American Philosophical Society Vol 55 Pan 3 June 1965 "The Antikythera Ship") the plank to frame fastenings were in many cases driven through tennons, showing clearly that this was a shell first construction.

Plank to frame fastening was on 250 to 300 mm centers, using 20mm oak treenails. These had been made with a drawknife or plane, not turned. Although we found copper nails, these seem only to have been used at butt ends of very long planks, and in scarf joints.

The 20mm treenails correspond to 3/4 inch english measure, it is interesting that treenails in plank on frame vessels of similar size, from 1600 onward, seem to average 1 1/4- 1 1/2 inch. This is an indication of the high sophistication of the Roman shell first shipwright. It is clear that he was depending on the strength of the tennoning for a good part of the structural strength of the hull.

Framing was 153 8mm, or 3 1/2x6 inches and was live oak. This is very light when compared with 18th century frame first practice. A typical ship, the Lord Dartmouth, of 1774 with keel for tonnage of 76 feet breadth 27 feet, had lower futtocks of white oak sided 10 1/2 in the middle running to 9 inches in the upper end. (American Neptune Vol Iv 1944 pp 207-212 given in W.A. Bakers Maritime History of Bath Maine 1973 pp 101 Iff).

Stringers or Ceiling was Pinus Sylvestris and measured about 200 by 60 mm. It was only recovered in one small area across two frames It appears to have been treenailed with oak treenails driven into frames from the inside.

The Keel survived as an extremely fragile fragment of oak. The two suspected keel pieces were worm eaten and very fragile: They both measured about 450mm square. This compares well with Lord Dartmouth's 13x 15 Inch Keel.

The Mast Step was elm. The largest piece of wood, measuring 220cmx40 cm.40 cm Approx.Notched at each end (to take frames??) with an approx 55 cm by 15 cm deep slot cut in its middle. Found at the extreme southern end of the excavation, not connected to any other timber. It does not appear to have been attached to other timbers, as treenails and fastening nail holes are not apparent. (Note that this piece has not been thoroughly studied, because of its weight and fragility, and the absence of lights and lifting equipment in the cellar where it is stored).

I have proposed elsewhere (See History of Seafaring, Ed. George Bass, Thames and Hudson 1972, p. 72, fig. I I) that this massive piece is the step for the Artemon of a vessel similar to the well known E u r o p a graffito from Pompeii. If further study shows that there are indeed no fastenings, this would go far to prove that ships of this type had Artemon rigged so that the vertical angle-of mast and sail could be changed at will by adjusting the backstay. We are now planning further research on this interesting possibility.

Whales: No. IAF seems definitely a whale, as its average width is 28mm and its thickness averages 9mm, as opposed to the standard planking thickness of 72mm or a little under 3 inches. This compares well with Lord Dartmouth 3 inch bottom planking and 4 inches streaks below the whales (4 inches = 103 mm approx) IAL, although the same width as the rest of the planking, is definitely thicker.

The Torre Sgaratta ship, as we have seen, is very lightly framed compared with vessels of similar tonnage built in the tradition that had emerged at the end of the 18th Century, typified by Lord Dartmouth. There is a good engineering reason for this. (Personal communication with Parker Marean 111, Naval Architect, of Wiscassett Me. USA). Large frame first vessels which are conventionally planked, are traditionally caulked. Lining off planks so that they had a proper caulking seam with a slight gap outside, but tight inside so that caulking could not be "driven through" was a craft specialty in 19th century shipyards everywhere. When the vessel was launched and "took up", the planking swelled against itself with the help of the caulking forming a rigid structure. In short, the compression created by the pressure of plank on plank was an important factor in the strength of the hull. This compression had to be supported from the inside: Thus the massive framing and thick fastenings of traditional frame first vessels to provide the tension reaction. In the case of the Torre Sgaratta ship, lighter frames were appropriate, as the tension reaction produced by the swelling of the pine planking was taken up by the tennons and the dowels (Treenails) that held them. This may well explain the longevity of the Torre Sgara t t a ship and others of her type. A Frame first, conventionally planked and caulked vessel can only be kept watertight so long as she can hold her caulking. Once plank to frame fastenings loosen, she must be refastened: If framing is rotten, or so penetrated by fastenings that it will not hold the plank in place, it must be replaced. The finite ability of framing to hold fastenings rather than the longevity of materials limited the useful life of vessels like Lord Dartmouth to 15 to 25 years.

Drawing I5 (not shown here) shows the fastening pattern of a typical part of the Torre Sgaratta ship. Plank to frame treenails are shown as black dots. It will be seen

that the pattern is irregular, although the appearance of treenails next to each other seems to indicate refastening with treenails, near other treenails: Additional evidence that the ship was old when she sank. the fastening pattern of a frame first vessel is very different. The first set of treenails would be driven at the top after and bottom forward part of the plank as it joined the frame. When refastened, a third treenail would be driven top forward: At the next refastening bottom aft. The final fastening would be driven in the last possible place that had strength to hold it, the middle. When that ceased to hold the vessel was worn out, and had to be condemned unless she could be reframed. It appears then, that ancient shipwrights conceived of this kind of framing as being a supporting part of the whole rather than the main strength element.

Additional evidence for this is what seems from the evidence to have been general practice in vessels of this kind: frames did not run to the keel and were often not

attached to floors.

Boxing

The practice of installing a new layer of planking over an old one was called "Boxing" in the 18th century. It does not appear to have been very common, but was definitely used to rehabilitate some kinds of old vessels. Double planking is still used in high quality yacht construction, where synthetic compounds make a seal between the layers. However, in view of the nature of the frame first concept as described above, it is probably not very effective as a repair method unless done over a framing system which is still sound. In the case of a tennoned hull condition of the framing would not be nearly so critical. Both the Titan and the Grand Congloue ships appear to have been "boxed" (see reconstructions of both keel sections by Ch. Legrand in AITI 1961 p. 70.) It seems likely that the additional layer of planking in both hulls is part of an extensive overhaul rather than original construction. Could the patches in the Torre Sgaratta ship have been a preliminary step to "boxing" the whole hull?

Further possibilities for study: Luckily, the timbers from the hull remain in good condition in the Castel San Angelo in Taranto. There is a great deal more to be learned from them. New evidence produced by the very competent study of the Lacydon ship (Le Navire Antique du Lacydon by J.M. Gassend, MusCe &Histoire de Marseilles), which was much better preserved, gives us a new approach to the Torre Sgaratta ship. Although the vessels are not the same size, they are probably from about the same date of construction, and exhibit similar techniques: The pattern of the inner stringers, for instance, seems to resemble what we see at Torre Sgaratta. The theories of the construction method of the Lacydon ship which resulted from a study of whether treenails were driven from outside or from inside are an exciting advance, and we should take a better look at the treenailing of Torre Sgaratta.The patterns may be similar: If so the work of Gassend et al., applied to Torre Sgaratta will take us another step towards understanding shipbuilding in antiquity. In my professional work as a marine surveyor, I have inspected hundreds of wooden vessels, large and small, of many types, built of widely differing materials. It is a conspicuous fact that framing nearly always deteriorates before the outer planking of the hull, unless a hull's bottom planking has suffered damage from worms, which only happens if the vessel is neglected. It has been remarked by Richard Steffy and others, including the shipwrights who built the Kyrenia Ship Replica, that shell first, tennon construction is much more expensive in both labor and materials. However, if a well built shell first ship lasted a lot longer than a frame first ship, this comparison might be negated. An intensive study of refastening patterns in both ancient and modern traditional ships might solve the problem.

Acknowledgements

A full list of those who contributed to the project would take more space than the comments published here. However it seems appropriate, as this is being published in Greece, to mention the Greek organizations and individuals that

helped us: Epirotiki Lines; The Nikos Kartelias Diving Center (Piraeus); Leonidopoulos and Sons (Piraeus); Photo by Peter Throckmorton; Drawings by Joseph

Conroy, Diana Wood, Joan Throckmorton and Roger Wallihan (Surveyor).

Peter Throckmorton

Nova University Oceanographic Center,

8000 N Ocean Drive, Dani Fla 33004 USA

Torre Sgaratta Shipwreck Update

February 2011

by Robert C. Vose III

Robert Vose, known to all of us as Terry, was a member of the Torre Sgaratta Expedition from the beginning and has continued almost single-handedly to ensure that the legacy of the work done by us all is carried out well. Here is his latest report:

I have recently returned from a three day visit to Taranto, Italy, to determine the current status of the material excavated in 1967 and 1968 during Peter Throckmorton's expedition, sponsored by the University of Pennsylvania, the National Geographic Society and the Littenaeur Foundation for the excavation of a second century A.D. Roman stone carrier merchant ship. She probably sank in a storm, a Sirocco, a southerly wind storm, which did not allow her to sail away from a south facing coast near Taranto. Her cargo of marble, about 100 tons, was possibly destined for Rome, originating from Asia Minor and the Greek islands. She sank about 550 m off the coast on a white sandy bottom in about 40 feet of water.

With a great deal of effort from my American friend and translator Rosetta Nasisi, I finally located my old friend and longtime head of archaeology for the province of Puglia, Dr. Angelo Alessio. I met with him and his two assistants, Angelo Raguso and Marcelo Nitti, beginning with a two hour to recap the last 15 years, with Marcello translating. For the next day and a half, the two aids, myself and my wife Judi, visited Castello Argonisi to see the wood and the five sarcophagi, the storehouse to see the mallet, a naval hospital to see the remaining marble and then a 1 and 1/2 hour drive to Nardo, to visit the new waterlogged wood conservation laboratory.

I am sincerely indebted to Dr Alessio, Angelo and Marcello for their friendship and generosity for their time spent with us and for the exciting new information about the Torre Sgarata Ship Wreck Project. It turned out that I had been diving with Angelo in 1995 looking for the wreck site and the gentlemen taking care of in a conservation lab remembered me from the 1995 visit. These former connections made this visit that much more amicable.

Wreck Location

The exact wreck site can certainly be rediscovered, as we left two sarcophagi on the edge of the excavation for later location and research. The site might be found by doing an aircraft fly over on a no-wind day to try to locate the two sarcophagi. The wreck site is 550 meters off shore and I have two photographs which would be of help locating it.

Information and Questions from my Trip

Marble

At the Castello there are three nice sarcophagi in the paved drive-in courtyard entrance with no TSG numbers visible. I do not think they are from the Torre Sgarata wreck.

There are two more sarcphagi in the lower grass courtyard, one is grayish with a side eroded away and the other looks fine from two stories above. I took a photograph from above.

At the Naval Hospital in Taranto there are 25 sarcophagi and blocks. Numbers 13 and 14 are there, and at least one or more have been broken in the moving process.

How did the Romans cut very thin sheets of marble?

Could trapezoidal stone anchors with a hole in them possibly been used in a stone dock or pier to tie ships to? They would have had to have been laid flat and locked into the surrounding blocks with large angle cut blocks.

Wood at Castello Argonessi

Mallet

The stone cutter’s mallet looks outstanding! It was conserved by David Leigh, one of our divers, at West Dean University and I had it returned to Taranto in 1997, The conservation department in Rome inspected it and said the job was an excellent one. The mallet is housed in a secure offsite storage area in the great padded layered box in which it was shipped. I was thrilled to hold it in my hands after not seeing it for 42 years since I found it.

Planking

The three big tanks of water at the Castello have been kept full! The large long tank has the big planks and wales in it, on racks and is maybe 5 feet deep. The medium tank (stainless) has planking in shorter lengths, maybe eight of 4 or 5 feet, on edge and separated with brackets. Another medium tank with just the artemon step in it is full and looks perfect.

Small pieces

All the bathtubs, urinal troughs and basins have completely dried out years ago. (maybe 15 or so). The contents should be recorded by tag number and photographed with a scale and possibly disposed of later. Is there anything that can be done to reconstitute the dried out waterlogged wood?

C)What preservative should be used for the Torre Sgarata wood?

Waterlogged Wood Conservation Laboratory in Nardo (about 500 sq m)

This is going to be the only laboratory of its kind in Italy. I visited it in 1995 and the building was then just completed, but there were no funds to install plumbing or equipment at the time. Over the years equipment has been slowly added to the basics. It was a great revelation for me was to see an array of five large tanks with the middle one of shiny stainless steel. This is the tank that I had custom-made for the artemon step. I wanted it to be in memory of Peter Throckmorton. Of course, I was never really sure that it was ever completed. The other tanks are not fabricated in stainless steel, but of good size and all plumed with pumps, heaters, filters and gauges. There are two huge stainless work trough tables, about 3' x 12', with center drains. To move objects in and out and around the inside the building there is a 5 ton chain hoist on a track.

The MOST exciting news from the archaeologists is that the Italian Navy is going to move all the TSG wood over to the laboratory from the Castello in a month or so and start conserving it. When they have finished with the Torre Sgarata wood they will re-excavate the Nardo ship which is off shore nearby. When they start bringing that wood up, they will immediately start conserving it in the laboratory.

What an extraordinary visit we had!!!

For me it was also a memory visit to remember Peter and Joan Throckmorton and Kim Hart who are no longer with us.

Robert C. Vose III (Terry)

coin of Commodus from TSG dating to 180 AD

Naval store yard - all Roman cargo

Diving vessel Archangel at site - Italian Coast Guard helicopter photo

Returning to castle after a day's diving

Terry checking air hose to dive site - Sam coming into shore in Zodiac

Ben Fuller heading to shore

Joan diving on the wreck

Archangel anchored at site