mo'olelo Hokule'a click for Page One

hokule'a mo'olelo3 click for Page Three

The Founders

Herb Kane

from Hawai'iki Rising - a book by Sam Low

to be published in 2011

Two men - Herb Kane and Ben Finney - share a vision of an ancient canoe

In 1968, an imposingly tall part-Hawaiian named Herb Kawainui Kane was working in Chicago as a commercial artist on an advertising campaign that featured a giant vegetable man - the Jolly Green Giant - who presided over a mythical Valley of Plenty. But as he sketched the affable Goliath, Kane found himself distracted by other visions swirling in his head - images of large ocean-going Polynesian canoes.

Herb was born in Garrison Keilor’s iconic American town – Lake Woebegone – to a Danish mother and Hawaiian-Chinese father. “My parents were on their way through Minnesota,” he recalls, “and roads and cars being what they were in nineteen twenty-eight, and my mother being in a state of advanced maternity, she delivered in Stearns County Minnesota which is the location that Garrison Keilor avers is Lake Woebegone.”

Herb grew up in both Hawaii and Wisconsin, the family moving back and forth. He finished high school and did a stint in the Navy. He then studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He took courses in anthropology at the University of Chicago, a hotbed of the discipline, and briefly considered a career in the field. He married, had kids and prospered. He bought a house in a little town called Glencoe on the shore of Lake Michigan “because they had a nice beach and a sailing club.” He learned to race catamarans and crewed on a yacht from Maui to Honolulu. He traveled often to the islands where he befriended the famous anthropologist Kenneth Emory of the Bishop Museum.

Herb read the journals of Cook and other early explorers. He studied the drawings of canoes they published. “I saw that some of them were very clumsy. What I read about the canoes did not correspond to them. In those days, people were trained to draw headlands and distinct landforms in the Navy Academies for recognition purposes. It was a part of cartography but that did not make them artists - their drawings were all out of proportion. The figures on the canoes, the sails, were out of whack. So I wondered ‘what did these damn things look like’? I got very curious and I started researching.”

Kane’s research took him to a famous book – Canoes of Oceania – reams of text and thousands of drawings, paintings and sketches of canoes gleaned from early European explorers by A. C. Haddon and James Hornell. Armed with a letter of introduction from Kenneth Emory, Herb sent queries to world famous museums. Responses poured into his Glencoe studio. He sat at his drafting board and redrew the canoes, smoothing their crude lines into seagoing shapes. “Having synthesized all these fragments into drawings, I was curious to see what they looked like on the sea with people on their decks.” He began to paint a series of illustrations that would inspire a stunning revival of interest in Polynesian origins and, more important, a search by Hawaiians themselves for their cultural roots.

Among Hawaiians today there’s a notion that a call has gone out to their mainland brothers and sisters. “Come home,” says the call, “we need you to help us reclaim our culture and our land.” No one is keeping track, but in the last generation or so, thousands of Hawaiians have heeded the call. Herb was one of them. Hawaiian artist and cultural practitioner Sam Ka’ai put it this way: “A man on Bear Island in Lake Michigan at the Chicago Institute of Art thought of the old songs. He started to paint pictures of waka (canoes). First they were Maori canoes, then Marquesan canoes - then more elaborate ones - then there were Hawaiian canoes. He was up there in Chicago. Why would he do that? Because he has this ma’a, this tattoo. It’s not a tattoo on his skin, it’s imprinted on his heart. His name is Herb Kawainui Kane. His spirit started to move.”

In 1970, this spiritual awakening caused Herb to move back to Hawaii where his canoe paintings were exhibited, reproduced as prints and on postcards and calendars. Their enthusiastic reception reinforced Herb’s curiosity – how did these canoes sail? Were they seaworthy? Could they carry large cargoes of people and goods? “What I really wanted to do was build one and take it out and find out. A lot of people didn’t get it. They thought I was going to build a canoe as some kind of monument. They were rather appalled when I explained ‘no this is something I want to take out and actually sail.’

One of the few people who knew precisely what Herb had in mind was Ben Finney.

Ben Finney

Ben Finney is a lean six foot three Californian with sandy hair and blue eyes. He grew up in San Diego surfing and diving for abalone. He learned to sail catamarans. He attended Berkley where he “wandered from engineering, to humanities, to history to anthropology.” It was the fifties and jobs were plentiful, so he was indulging his interests. Ben traveled to the Hawaiian Islands to surf and became fascinated by Polynesian culture. “My question was how did they adapt so well to the sea? Everything I read in anthropology was about land people. The Polynesians were a sea people – how did they learn to use the ocean so well, to create this ocean based way of life?”

At the University of Hawaii, he met Kenneth Emory, then the world’s foremost authority on Polynesia, and folklorist Katherine Luomala who supervised his master’s thesis – “Surfing, the History of an Ancient Sport” which was published, rare for a scholarly treatise, and is now in its second edition. Loumala introduced him to a book called “The Ancient Voyagers of the Pacific” by Andrew Sharp.

“I don’t like this book and I want you to read it” Loumala told him.

Andrew Sharp had accepted the scholars’ conclusion that Polynesia had been settled from Southeast Asia, but he could not accept Captain Cook’s earlier theory that Polynesians had navigated their canoes by sun, moon and stars. How would they have plotted their course over thousands of empty sea miles without a map or have found their latitude and longitude without instruments? Sharp thought Polynesia was settled by accidental voyages – by castaways blown off course in storms. “On occasion,” he wrote, “voluntary exiles, or exiles driven out to sea, were conveyed to other islands on one-way voyages in which precise navigation played no part.”

“I didn’t believe it,” Finney remembers. “My response was partly emotional – I had been thinking of the Polynesians as great voyagers and this guy says they are not. Here are the Polynesians, sitting in the middle of this huge ocean and they’ve got these big canoes – the ones seen by Captain Cook on his voyages – so they must have sailed here. Sharp said flatly that you can’t sail more than three hundred miles out of sight of land without instruments because of navigational errors. But you have Hawaiian legends of people going back and forth between a place called Kahiki which is arguably - but not necessarily - Tahiti. Was Polynesia settled by competent sailors on purposeful voyages of discovery, or by accident – by storm tossed castaways? So the obvious idea occurred, ‘well, we have to rebuild an ancient canoe, relearn how to navigate and sail it and take some of the legendary voyages.’” Ben had the wits to know this is not something that a graduate student should be thinking about. You have to get your degree first. So he earned his Ph.D in anthropology from Harvard after arduous study in Tahiti. But all the time he was thinking about building a canoe.

In 1966, Ben got a teaching job at the University of California in Santa Barbara. He was newly married. He had a few thousand dollars saved up. He still dreamed of building a big canoe to sail throughout Polynesia but he settled on a more prudent first step. Why not build a smaller canoe of the same type and test that? “There was a mould for a Hawaiian shaped hull in California,” he recalls. “I could plunk down five hundred dollars and put my labor in and end up with two hulls for a forty foot double canoe.” He developed the project under the non-profit umbrella of his university, recruited some students as labor, and launched the canoe within a year. Mary Kawena Pukui, famous Hawaiian scholar, named her Nalehia – “the skilled ones.”

Ben received a grant from the National Science Foundation to find out how much energy was needed to paddle her. He shipped Nalehia to Hawaii where he conducted oxygen uptake tests and discovered that paddling long distances would take more water and food than the canoe could possibly carry. Clearly, Polynesian explorers must have been skilled at harnessing the power of the wind.

In the fifties, when Ben was in the islands as an undergraduate at the University of Hawaii, most Hawaiians seemed oblivious of their cultural heritage. “It was a thing of the past,” he wrote in his book – Hokule’a – the Way to Tahiti – “and better left that way seemed to be the common attitude on the part of Hawaiians, then a dispirited minority comprising less than one fifth of Hawaii’s multiracial population, dominated by Americans of Caucasian and Asian Ancestry.” But now, returning to the islands in 1966, he found new stirrings among Hawaiians. “Young Hawaiians who had grown up speaking only English were trying to learn Hawaiian and were studying old forms of chanting, dancing and other practices of the ancient culture.”

Finney knew some surfers and canoe paddlers at the Waikiki Surf Club – people like Rabbit Kekai and Nappy Napoleon, big names in those days. He enlisted them to crew aboard Nalehia and their fame soon attracted others. Among them was a young eighteen-year-old nicknamed ‘Hoss’ because he was big and clumsy. Hoss had just graduated from high school and was having trouble finding a job. He became deeply involved in the canoe. He soaked up Ben’s stories of his early ancestors. A few months after their first acquaintance, Ben met Hoss on the beach.

“Hey Ben, I got a job now,” Hoss told him.

“Yeah, what?”

“Working for the telephone company.”

“How did you get that?”

“Well, I went for the interview and I told them about the canoe project and what we were doing and I got so enthusiastic they said, ‘well, you are an enthusiastic guy, we’ll hire you.’”

“It was a revelation,” Ben remembers, “Look at what the canoe can do for Hawaiians. This project is not going to be another Kon Tiki – eight haoles on a raft. We will make it a Hawaiian-Polynesian project and I will get my Hawaiian and Tahitian friends involved.”

Designing Hokule'a

Early in 1973, Ben Finney met with Herb Kane and Tommy Holmes, a famous island waterman from an elite kama’aina family. “We started talking among ourselves,” Ben recalls,“ and we said, ‘well let’s do it. Let’s build a big canoe and sail to Tahiti and back.’”

Their first task was to come up with an appropriate plan for the canoe. “We wanted to get an approximate design that would be generic to the age of ancient exploration,” Herb recalls. But how to choose the best design from all those drawings made by early explorers? Herb had studied anthropology at the University of Chicago and he was familiar with the “age-area” theory which proposed that the cultural attributes most common and widespread in an area must be the most ancient. A three dimensional visualization of this theory resembles what happens when a stone is tossed into a still pond. Where the stone hits is the source of a cultural innovation - a new canoe design, for example - and the ripples represent how the design radiates out over time. Innovation may occur at the source, producing more ripples, but the original early designs are distributed far and wide. Hence, those canoe designs that are the most widespread in an area – are the earliest.

“I looked for hull and sail design features most widely distributed throughout "Eastern" or "marginal" Polynesia (including Hawai'i, the Marquesas, Tahiti, the Cook Islands and New Zealand) when Europeans arrived,” Herb recalls, “and I figured these were the most ancient because they must have been common features in the era of exploration and settlement. To these features I added some distinctively Hawaiian stylistic elements-the end pieces and arched crossbeams.”

Archeologists debate whether the first arrivals in Hawaii came from the Society islands or the Marquesas, but there is agreement that voyages between Tahiti and Hawaii continued until sometime between the 12th and the 14th century. Then they stopped. Perhaps the islands were filling up and Hawaiians had decided to protect their precious real estate from new Tahitian migrants who they perceived as interlopers rather than ancestral brothers and sisters. Whatever the reason, Herb figured that when long distance voyaging declined, Hawaiians took to paddling their canoes rather than sailing them on the relatively short trips along the coast or between the islands. Chiefs traveled with a large number of warriors who could man the paddles and paddling offered the advantage of being able to power through calms or travel directly upwind. Herb surmised that the shape of canoe hulls changed to accommodate this change in power, from the deep vee-shaped hulls of sailing canoes to the more rounded and shallow hulls of canoes that were paddled – like the ones Cook discovered in Hawaii. Rounded hulls, like Ben Finney’s canoe, Nalehia, were not suitable for sailing. “Hulls of paddling canoes are round and are maneuverable but do not track well if you try to sail them,” Herb says, “making about seventy-five degrees to the wind in sheltered waters. On the open sea, in strong winds and buffeted by waves, such hulls would no doubt skid off the wind.”

Modern sailing catamarans have deep, flat-sided hulls which make them extremely fast and allow them to sail relatively well to windward. To maneuver such hulls, however, requires powerful stern-hung rudders – an innovation unknown in Oceania - and the hulls stand high out of the water and are affected by the wind. They also tend to plunge in heavy seas. Ben agreed with Herb that their canoe would be modeled on an ancient Tahitian variant, called a pahi, which had a curved vee-shaped bottom and rounded sides. The underwater vee shape would allow the canoe to sail to windward. The rounded sides would prevent her from plunging in swells. Given the distance between the predominant Pacific swells, Herb figured that sixty feet was a good size for the canoe. The hull would have tumblehome – a graceful inward curve at the top - because it strengthens the canoe laterally.

Herb enlisted others to help. Kim Thompson, an architect, designed the bow and stern pieces - the manu. Rudy Choy, an expert naval architect who had designed modern catamarans and written a book about them, helped with the line drawings for the hulls. The canoe was substantially funded as a part of the national bicentennial celebration, so it had to be ready to sail to Tahiti by 1976. That, and because there were no shipwrights who could fashion a canoe from a log, led them to build her of cold molded plywood covered with fiberglass.

“We needed to raise money,” says Ben Finney, “so we decided to form a non profit corporation - the Polynesian Voyaging Society. I drafted a succinct statement – ‘we are going to form the society to study Polynesian voyaging and do experimental voyages to gain information to model Polynesian migration and voyaging.’”

“We set a three year time table,” says Herb, “the first year to raise money, the second to build the canoe, the third to learn how to sail her and make the trip – from 1973 to 1976 to do the whole project.” They named their canoe Hokule’a – Star of Joy - the Hawaiian name for the star Arcturus, which reaches its zenith directly over Hawai'i and may have been a prime navigational guide for ancient navigators seeking the Islands.

Herb convinced Dillingham Corporation to provide a secure place to work - a large industrial building with a concrete floor. Warren Seaman lofted the lines and began work on the hulls, then boatwrights Curt Ashford and Malcolm Waldron took over, assisted by Tommy Heen, Calvin Coito and many volunteers.

The projected cost to build Hokule’a was a hundred thousand dollars, an enormous sum of money in 1973. To raise the funds, Ben Finney began writing grants to foundations known to fund anthropological research. The canoe was an exercise in “experimental archeology,” he wrote, a new field of study that tested ancient technologies by building something – a catapult, a fortification, a Roman chariot – and experimenting with it to see how it worked.

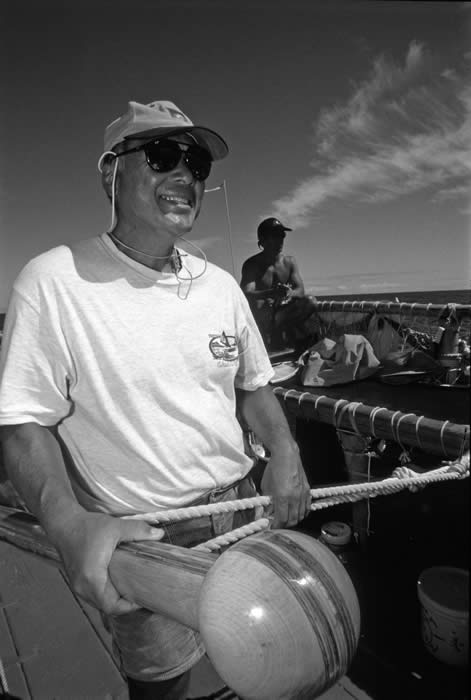

Photo by Steve Thomas

c. 1984

Mau Piailug

from Hawai'iki Rising

In 1975, just before Hokule’a was launched, Mau Piailug arrived from his home island in Satawal to guide the canoe to Tahiti.

Among the tall muscular Hawaiians at the launching ceremonies was a man smaller in stature with darker skin and cropped curly black hair. He was a newcomer, having flown in from Micronesia on the very day of the launching. But from the way the crew treated him, even a casual observer could perceive that he was regarded with a kind of awe. His name was Pius Mau Piailug. He would navigate Hokule’a to Tahiti in the ancient way – without chart, compass or sextant – finding land instead by a world of natural signs. Mau’s home is a tiny coral atoll – one of many that stretch like a string of pearls across the Pacific from Yap Island in the west to Ponape Island in the east – the Caroline Islands of Micronesia. His home island is Satawal, a tiny upthrust ring of coral and sand about a mile in diameter. Satawal sits alone in an empty part of the Pacific, five hundred miles south of Guam. Here Mau lives very much as his ancestors did. He harvests taro from a garden behind his house. He gathers breadfruit and coconut from his trees. He bathes every day in a freshwater pond, surrounded always by the beat of surf on the encircling reef. Life on Satawal is perhaps the nearest possible to a dream of South Pacific paradise.

Along Satawal’s sheltered shore, outrigger canoes are drawn up beneath lofty houses roofed with palm fronds and open on all sides. These vessels are called proa. Their design is the result of perhaps a thousand years of evolution, yet they are surprisingly modern – so much so that in 1980 a western sailor built one of modern materials and with it won the OSTAR single-handed race across the Atlantic. A proa’s narrow hulls are shaped like airfoils so that water flowing over them tends to lift them to windward, making them extremely efficient – and fast. They are fashioned with materials that Satawal provides – breadfruit planks for the hull, coconut husks and breadfruit sap to keep the water out and sennit rope fashioned from coconut to hold the planks together. Satawal’s isolation, and that of the other Caroline islands, has resulted in the preservation of a seafaring life that is unknown elsewhere. Mau and a handful of Micronesian sailors still follow an ancient way of navigating handed down by generations of their ancestors.

Mau’s grandfather was a famous pwo – a man who had learned the technical art of navigating, passed his initiation and mastered the spiritual arts - tools that are beyond western logic. It was an informal but rigorous course of study that took place on the beach where he watched for signs of weather with his master and learned the stars; and on a canoe where he learned to distinguish between large swells stirred by steady trade winds and evanescent ones motivated by brief storms. The teaching continued in a canoe house by lantern light where the master unrolled a woven pandanus mat and laid out thirty-two brilliant white lumps of coral in a circle to represent the rising and setting of stars. It was a world of words but no writing. All knowledge was conveyed orally by the “talk of navigation” or by the “talk of the sea.” Everything was committed to memory. Mau’s grandfather chanted as he pointed to the star houses, “Tana Mailap,” he began, due east - the rising of Mailap - a star western navigators call Altair. “Tana Paiiur,” he continued, “Tan Uliol, Tana Sarapul, Tana Tumur, Tana Mesaru, Talup, Machemeias, Wuliwiliup” pointing to stars equally spaced from east to south, one quadrant of a compass defined by stars. It was a beginning lesson called paafu – “numbering the stars” – and it conveyed a way of finding direction that Arabs crossing the great empty spaces of the Sahara might have found familiar and that Polynesians must have used in the great days of open ocean voyaging. As he spoke, the master’s voice blended with the beat of swells against the island’s reef and the clacking of palm fronds overhead. When his grandfather completed one quadrant of the compass, Mau would repeat the chant. Then on around the circle until each star house had been recalled. Then came aroom, reciting the reciprocals of the star houses; then wofanu, the sailing directions to hundreds of islands. Then came fu taur, the alignment of stars with island landmarks to find a passage through the encircling reef. Then he learned etak, how to dead reckon his position by imagining his canoe in the center of the star compass and islands sliding by on each side under star paths – a unique Micronesian mental system of triangulation. These are only a few of the lessons that were passed on verbally in a cycle of repetition that stretched back dozens of generations.

Anthropologists distinguish between the status a person receives by his birth and the kind that he earns by his individual talents. Most societies, even those rigidly divided into various ranks, provide some way of motivating and rewarding achievement. The Aztecs, Maya and the Pueblo dwellers of the American Southwest recognized the abilities of warriors. Pueblo dwellers also appreciated the ability to entertain and so they gave rank to clowns, and the ability to philosophize, so they provided yet another rank for those who thought and spoke well. On Satawal, three chiefs regulate the island’s affairs. They have the power of placing a kapu (as Hawaiians would call it) on various activities. They can ban fishing or harvesting breadfruit, for example, to preserve food stocks. The chiefs are born into their rank. They are the descendants of island dynasties. But their power ends at Satawal’s fringing reef where that of the navigator begins. “At sea, I am the chief,” Mau once explained. “To be a palu (navigator) you must have three qualities: pwerra, maumau and reipy (fierceness, strength and wisdom). …if you are not fierce, you are not a palu: you will be afraid of the sea, of storms, or reefs; afraid of whales, sharks; afraid of losing your way – you are not a navigator. With fierceness you will not die, for you will face all danger …that is a palu: a palu is a man. On the canoe I am above the chief. He has to do what I say.”

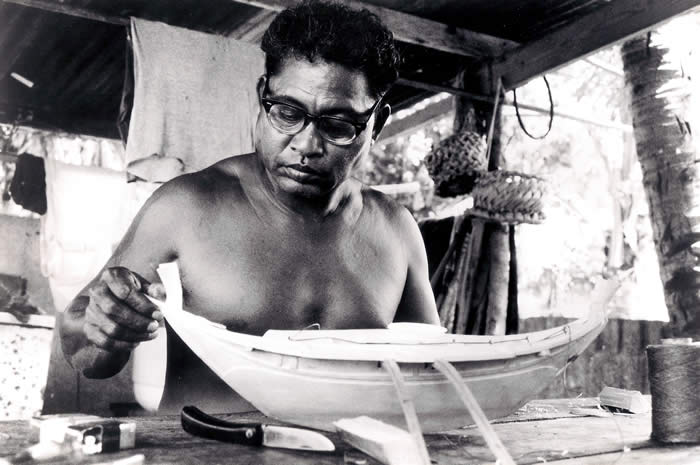

In Hawaii, Mau said little and accomplished much. When Hokule’a’s booms broke under the strain of sailing, he took out an adze and carved new ones. The booms were curved, so he fashioned graceful scarf joints and joined three pieces of hau with rope lashings. He did the same for the gaffs when they broke. When there was nothing to do, he sat quietly and carved a scale model of his proa complete with rigging and sails – a work of art so perfect it could have graced a museum display case.

Nainoa had heard so much about Mau that he had become endowed with the ability to do miracles. Nainoa watched his every movement and tried to make sense of a man who could navigate a canoe across thousands of miles of ocean without a chart or a compass. “No one really knew how it was done, so it kind of got into this mystical realm out of our own ignorance. That was what my perceptions were when I looked at him – you had someone here who could do things that none of us could.” Nainoa didn’t know what to say to Mau so he said nothing.

Another crewmember, Shorty Bertelmann, was equally mesmerized. “I watched Mau as he worked and how he used an adze with such precision and I had never seen that before.” Shorty was from the Big Island. He had been born into a paniolo (cowboy) family and he knew how to ride and rope cattle the way his forefathers had learned on the Parker Ranch. He was likewise a fisherman and a surfer. He is a lean man, graceful, almost delicate. His face is composed of angular planes. His glance is gentle yet intense. “There was something about Mau that I could see right away,” Shorty recalls. “He was not like a normal man – he knew things that no one else knew.” Shorty spent as much time as he could sitting next to Mau. Asking few questions, he tried to learn Mau’s skills by repeating them. “I just spent a day with him trying to help him when I could and another day and another and after a while it seemed like he welcomed me to be with him and I was kind of surprised because I never thought that a man like him would pay any attention to a person like me.” Shorty learned how to hold an adze and how to swing it gently but with sufficient force to reveal shapes hidden in wood. “The way that I learned from Mau was by watching what he did and trying to understand how he did it - by going out and figuring it out for myself and then asking him if that was the right way. You don’t just go up and ask him to teach you. It’s not a classroom with handouts and lectures.”

Mau watched the crew carefully and he judged them silently. He looked for the nascent qualities that would serve a man well at sea. He looked for pwerra, maumau and reipy. He respected stillness in a man, humility accompanied by knowledge. He looked for a willingness to learn. And he waited. In Satawal, a master does not proselytize. His students come to him, driven by their innate curiosity. Those who display talent and discipline become his apprentices. Among all the men and women who surrounded him, only two stood out in this way – Nainoa Thompson and Shorty Bertelmann. “When I look at them,” Mau recalls, “I'm thinking good guys because they like learn. I am not asking them. They come to me and they want to learn. They ask questions. I am strong for teaching them because their talk to me is good. That's why I decided to teach them.”

------------------------

...just his way of sensing things.

Dennis Chun: “I asked Mau, ‘How long it took you to learn to navigate?’ He said, ‘How long? One hundred fifty years.’ I looked at him and.... no way? He knew that I was puzzled. He looked at me seriously. ‘I learned from my great grandfather, my grandfather and my father, all of them teach me.’ He’s right, he’s the culmination of everything that came down to him. It made me think about it in another way.

And just his way of sensing things. He would be sitting down in his hole (compartment), writing in a notebook, or making one net or something, and I remember one time I was steering and I think I am doing okay and I feel this tug on my leg, and he goes, ‘Dennis, too high.’ I’m thinking, ‘how does he know?’ He just senses things.

We were sailing below the equator. It was weird. In 1985 we kind of hit two kinds of doldrum-like conditions, one in the normal place for it. We were stuck I think seven or ten days in the ITCZ area – we just got pounded and Nainoa got really tired. And we got out of that and - hey it’s downwind, downhill from there and then we hit this other section, a whole bunch of calms and the wind came out of all kinds of directions. It was between those two doldrums. It was really nice one evening, the whole day was nice, real mild but still fast, so we busted out the guitars. We were jamming, good fun. We were styling. Mau comes out of his hole and puts on his raincoat, a vinyl kind of raincoat, and pants the kind you buy at Costco. He puts this on and rubber bands on his ankles. We’re all having a good time. Good weather - and he puts on this stuff. Maybe a half an hour later the sky comes black and here we are, woah, put away our guitars, scramble to get on our foul weather gear. Rain for the next three days. How did he know? From there on - whatever he does - we follow him. That’s the time we came in on the tail end of a hurricane, Ignacio, three days. Within twenty-four hours we changed sails three or four times - busted ass - but we did it. He puts on his raincoat, doesn’t say anything. He feels these things even before we see them. Clay Bertelmann says, ‘Hey Mau, why you no tell us?’ He says, ‘you should know.’ It was a good lesson.”

...one hundred and one ways to use a coconut.

Billy Richards: “Mau is an incredible person. We were fortunate back then in learning from him. It was more than navigation. He taught us one hundred and one ways to use a coconut. Down at Snug Harbor he would teach us dances - in 1975 - because we were all living in the containers. Mau worked with us all day and at night we would have this star course – he would make you a star and then he would teach you this dance and as you move, the choreography of the dance is such that you understand the movement of the stars. Me – this star – in relation to you – your star – how we move together. He taught John (Kruse) how to make this Jew’s harp out of bamboo. He was our doctor. He was our mother. I went surfing at Queens one time and I crunched my knee. It got really huge. I came back to the container and he saw it. ‘You come.’ And he poured coconut oil on it and did this massage and the bruising went away. He was holistic. Navigation is just one part of him. There are so many others. For those of us who lived with him, or stayed with him down at the container we saw glimpses of it. And it is in my heart.”

Plenty sons I have here.

Mau Piailug stepped out of his culture when he decided to pass on his navigational arts to Polynesians. He endured criticism at home. But no-one on Satawal came to ask him about navigation, and he was afraid his art would be lost....

Harry Ho: “Mau said to me, ‘But you know, Harry, I no like to lose sail. I no like to lose the stars. So I like to come to Hawaii because people like to learn about the stars. That’s why I come. More people come. We go to New Zealand - same thing – people come. No matter where we go, people come to ask me for help.’

That was his whole thing. He wanted to help. He wanted to keep navigation alive.

‘My sons they have families,’ Mau told me. ‘They have problems. My youngest son Seasario may be the only one that will follow me. Seasario - for me, my last hope. But I got many sons here. Plenty sons I have here. So I no worry now – I have more sons. I have sons in Cook Islands. I have sons in New Zealand. I have sons in Marquesas. For me I feel good inside. I feel happy.’

He talked about Honolulu. ‘Too many people busy. I go Big Island where people stay all the time.’ There were more people who focused on navigation there. On Oahu, people are all over the place. He was more comfortable there than he was here.

His whole idea was to expand his horizons by trying to teach more people so his art would not get lost. He said he didn’t care what happened when he went back to Satawal. ‘The chiefs want to take away this or that. It doesn’t matter,’ he said, ‘they no can take away what happened over here (in Polynesia). They no can take away this. Everybody that comes inside here – in my heart – no can take. No can. It stays here with me (in my heart) - no can take.’”

-----------------------

...he talked to the stars...

Kimo Lyman: "Mau went to sea with an ancient wisdom that has been largely lost in modern Hawaii. In Hawaii today it is like the spirit and religion is separate from daily life and for him it is not. I remember that Mau, every morning before the sun came up he would be out there chanting. The 1986 voyage. I enjoyed the way he talked to the stars, talked to the winds, talked to the gods. Then he would say, ‘oh yeah, we get into this situation and I am going to make magic.’ I just loved it. Western man may call him a charlatan but he is not. He lived a life and he knew how to communicate. Inspiring."

Ohana Wa'a

by Sam Low

In 1995, a fleet of canoes gathered in the main harbor of Nuku Hiva in the Marquesas. They would journey together to Hawaii, the first voyage of the ohana wa’a - the family of canoes - in many centuries. I was aboard an escort vessel for that trip. here is my report...

Haka

The warrior's taut muscles gleam under a sheen of coconut oil. He stands perfectly still as the interrogator menaces him with a spear. I do not understand the language, but the meaning is clear.

"Why have you voyaged to our island? Who are you? If you come in peace, you are welcome. If in war, we will kill you where you stand!"

The interrogator's warriors are arrayed behind him along the beach. Further inland stand lines of young women dressed in short skirts of pili grass, their black hair glistening under the tropical sun. Over the visitor's shoulders, I see three large voyaging canoes, their double hulls rising and falling with the gentle swell, their crews poised to swarm ashore if violence erupts.

The interrogator steps back and stands proud before his warriors. The silence is tense. It is the visitor's turn to speak.

"I come in peace from a far distant island. I am a prince of New Zealand, descended from the first voyagers who settled our island. But if your intention is war, your blood will wash the shore clean."

I stand transfixed. The crowd jostles around me, pushing forward. A young girl giggles, breaking the spell.

I have just witnessed a "recreation" of an ancient scene, a ritualized greeting that was common throughout Polynesia in a time when powerful voyaging canoes plied the Pacific in great numbers. These canoes are replicas. The island's warriors are high school students, the visitors are men and women dedicated to the revitalization of Polynesian culture through retracing the ancient voyaging routes taken by their ancestors.

It is April 14, 1995. I am on the island of Nuku Hiva in the Marquesas. Assembled in the harbor after an arduous 750 mile voyage from Tahiti are seven canoes. Each is the recreation of an ancient design. They represent the Cook Islands, The Societies, New Zealand and Hawaii - the core cultural areas of the Eastern Polynesian triangle. In a few days, this fleet will sail from the Marquesas to Hawaii, 1700 miles across a trackless ocean wilderness. And they will find their way by the signs that once guided their ancestors - the arc of stars, the slope of ocean swells, the flight of birds.

My mission here is personal - a voyage back to my own roots. My father was Polynesian -- born in Hawaii but sent as a teenager to a boarding school in Connecticut. He stayed in New England, and died there, never having returned to the islands. I am returning for him.

In the Hawaii that my father grew up in, the population of native Hawaiians had been nearly eradicated by disease. The language was not taught, in fact, was forbidden in Hawaiian schools. Hawaiian culture was in danger of being lost. But in 1976, a remarkable event stirred the imagination of all Polynesians. Hokule'a, the replica of an ancient voyaging canoe, set out from Hawaii to retrace the mythic voyaging route to Tahiti. Sailing across 2200 miles of open ocean, the canoe was guided by one of the last navigators to know the signs written in waves and stars, Mau Piailug from the tiny Micronesian atoll of Satawal. After thirty days at sea, Hokule'a was welcomed by the largest throng ever to assemble in Papeete, the capital of Tahiti.

In 1981, I began work on a PBS documentary to celebrate the seafaring skills of my ancestors. I delved deeply into scientific studies of Polynesian prehistory to discover that linguistics, Carbon 14 dates, blood types, and the archaeological affinities between islands all confirm that the Polynesians settled the pacific by sailing east against the prevailing winds in powerful canoes much like Hokule'a. Later, I journeyed to Satawal to sail with Mau Piailug aboard his swift proa which he fashioned without plans or metal fastenings from the log of a breadfruit tree. At night, in his darkened canoe house, he unfolded a woven pandanus mat before me and placed 32 lumps of coral upon it to represent the rising and setting points of the stars that define his "star compass." He taught me the direction of ocean swells that he steered by when clouds obscured the sky. Mau allowed me to enter a world in which writing, maps, sextants and compasses were replaced by a knowledge of nature so profound that he could sail with confidence anywhere in the world.

"When I first set out aboard Hokule'a from Hawaii to Tahiti, I was afraid," he told me. "But then I remembered the teaching of my ancestors and I found courage. With this courage, I will never be lost."

Now, the spark kindled by Hokule'a's voyage has inspired other islanders to build their own canoes. Hence this fleet of Polynesian sail assembled in the harbor of Nuku Hiva. As I watch a line of dancers perform a graceful hula on the temple platform overlooking the harbor, I feel the power of my Polynesian ancestors - their mana - enter my soul. If this powerful emotion is possible for me, a Hawaiian by virtue of a small percentage of my blood, one born and raised on "The Mainland," what must it be like for the crews of the canoes?

Te au tonga

The Escorts

I have sailed to Nuku Hiva aboard Rizaldar, a powerful 43 foot Swan sloop. She is a one of seven escort vessels which will accompany the fleet on their voyage to Hawaii.

"Our first priority is safety," says Nainoa Thompson, leader of the expedition, "and so without the escorts to protect the canoes we would not be able to make these long voyages."

The escort fleet is varied. There is Goodwind, Captain Terry Causey, a 51 foot long sloop built in 1927 of iron plate. She was once a training vessel for German naval officers. Gershon II, Captain Steve Kornberg, and Kama Hele, Captain Alex Jakubenku, are steel motor sailors. Three Daughters, Captain Peter Giles, is 60 foot long Herrischoff Mobjack Ketch. Pozzuolana, Captain Joe Tragovich, is a ferro-cement sloop. On the Way is a 38 foot Morgan cutter-rigged sloop, modified for a single handed passage around the world by Captain Bob Jans. Rizaldar, Captain Randy Wichman, is a 43 foot Swan, the speed demon of the fleet.

The "admiral" of the escort fleet is Alex Jakubenku. Red-faced with a shock of white hair and bushy eyebrows, Alex is about 5' 10" tall. Russian born, he escaped the Nazis to fight with the French underground - the Maquis - during World War II. He is 71 years old, but looks 50. Alex appears to be an amiable bear but is known as a demanding captain.

"My boat, my life and the lives of everyone on board would be sacrificed to save the life of just one crew member of one canoe under our care. Without hesitation! I tell this to everyone who comes aboard and if they do not agree completely they are off my vessel. Simple as that."

It is not idle talk. In 1980, Alex was escorting Hokule'a on a training voyage off a lee shore when a terrific storm descended on the two vessels. Hokule'a's tow line parted and the canoe drifted perilously close to the breakers. Ordering his crew to don life-vests and swim to shore if the rescue mission failed, Alex took his ship so close to the breakers that spray from them swept his decks. Hooking up, he held the canoe off shore for hours until a Coast Guard vessel came to their rescue.

"Without Alex, Hokule'a would have gone ashore and been destroyed," says Nainoa. "He is awesome!"

Rizaldar's mission is different.

"We are Nainoa's eyes and ears," says Captain Randy Wichman.

As the "ears" of the fleet, Rizaldar maintains the communications net - originating a single side band "fleet roll call" twice a day. At 0830 and 2030, according to a standard protocol, each vessel relays course, speed, status of crew and equipment and intentions.

As the "eyes" of the fleet, Rizaldar has no canoe to escort but is constantly roving, visually checking the status of each canoe. The fastest vessel in the fleet, she is prepared to speed wherever she may be needed. On the voyage down to Tahiti, two days out of Honolulu, a crew member aboard Kama Hele suffered a serious wound. Rizaldar picked him up and sailed to meet a Coast Guard vessel speeding to the scene.

"We should have a big 911 stenciled on our hull," jokes one Rizaldar crew member.

The Southern Cross

Tuesday, April 18th. A full moon rises over the anchored canoes, spreading a silver sheen across the harbor of Nuku Hiva. The gentle light reveals a hidden shape in the surrounding mountains - the open palm of a giant hand. The canoes seem to rest in the flesh of the palm. At the mouth of the harbor, the fingers spread to form the twin Sentinels, spikes of lava guarding the entrance on either side. The Southern Cross lies on her side between the Sentinels. Tomorrow, in the time it takes for the Southern Cross to wheel across the sky, the canoes will set sail for Hawaii, 1800 miles away. As in the past, the fate of each canoe will depend on how well their navigators can read the patterns of the night sky.

To steer their canoes without instruments, the navigators use a modified version of Mau's "star compass." At the same latitude, the stars rise and set in the same place, night after night. In Hawaiian waters, for example, Deneb rises in the north east (46 degrees) and arcs across the sky to set in the north west (314 degrees) defining two points on the star compass. Shaula rises close to south east (127 degrees) and sets near the south west (233 degrees.) South is defined by the pointing stars in the Southern Cross. North is in the direction of Polaris.

April 24. On our second day at sea, I stand the midnight to six watch.

Our course is 320 magnetic. I decide to try steering by the stars. First, I calibrate my personal version of the star compass by the magnetic compass, then cover the binnacle. The Big Dipper is almost straight up and down. The stars in the bottom of the Dipper's cup line up with Rizaldar's tilted mast. The constellation stretches high so that when clouds obscure the cup I steer by the handle. I keep the Porpoise, one of my favorite constellations, off the starboard beam and the Southern Cross just over the top of the outboard motor stowed on the port rail. At about 2:30 A.M. the moon rises and sends a shimmering path across the swells, another guide to steer by.

By checking the binnacle every fifteen minutes and making adjustments as the stars wheel across the sky, I find that I can guide Rizaldar easily by the compass in the sky. But Mau and the others have no magnetic compass to check. They have memorized the rising and setting points of hundreds of stars. And I have chosen a clear night for my experiment. What must it be like to guide a canoe when clouds obscure all but a few stars?

Te'aurere

A canoe is lost

Sunday, April 23rd, 0830 roll call begins with Captain Randy Wichman routinely calling for the positions of the vessels. The routine is short lived.

"Break, Break, this is On The Way, I have lost contact with my canoe."

This is an emergency message. Position reporting stops. Nainoa, aboard Hokule'a comes up on the net to seek details - where, when, how.

"I lost contact with Te'aurere at 2040 hours in a squall and I hove to," reports Bob. "I stayed hove to until 0400 when the visibility improved, then I began a quartering search pattern. The last I heard of the canoe on VHF was at 2240. She was reporting that she was heaving to in another squall."

Losing contact with a canoe in bad weather is relatively common. But why was Bob unable to raise them again on VHF or single sideband? Could they be disabled? Even worse, could the canoe have gone down? Quickly estimating the drift of a disabled canoe, a box search area is established. On The Way will sail up the east side of the box and Gershon II will patrol the west side. Aboard Rizaldar, Randy searches the fleet frequencies for Te'aurere. On the 2182 megahertz band he finds them.

"Rizaldar this is Te'aurere. We experienced a serious battery failure last night and we lost radio contact." The signal is weak, dying. Randy requests approximate position.

Te'aurere heaves to. It will take four hours for On the Way to reestablish visual contact. The smooth handling of the emergency is a vindication of fleet procedures worked out before the voyage.

"You all did the right thing," says Nainoa over the net. "Good work."

Rizaldar takes up position near the fleet's eastern flanker - Takitumu. Having raced at nine knots to join up with her, we now stall the boat to stay with the canoe - moving due north at about six knots under a tiny fore triangle and reefed main.

Off watch, I try to sleep. The boat rocks gently. The sun slants into the main saloon, sending a square of light to pendulum over my bunk, up to the bunk above, then back down again. The single side band, tuned to the fleet frequency, spits and whistles and occasionally erupts in distant alien chatter.

Now begins the pattern of our voyage, one or two days of slow monotonous station keeping followed by a day or two of "flybys" - high speed dashes with all sails set to visually checkout and visit with one of the canoes.

Takitumu

Takitumu

Ancient shapes

To the eye of a Western seafarer, the shapes of the Polynesian canoes are unsettling. Takitumu's triangular sail tilts its apex to the wind, not the sky. The rest raise sails shaped like crab claws, with the largest area of sail aloft - the reverse of the Western Marconi rig.

"Ancient sails were made of woven fibers like lauhala (pandanus)" Hokule'a's captain, Chad Baybayan, once explained to me. "Modern sail cloth can take the strain imposed on the top of the marconi rigged sail. Lauhala would rip out. So I think the ancient sails were designed to spread the strain more easily across the fabric."

All the canoes are double hulled, catamaran-like. Their broad decks (42 feet long by ten feet wide for Hokule'a) are perfect for carrying large crews and cargo on voyages of discovery. And the Polynesians certainly built canoes twice the size of the replicas we sail today. Hokule'a's crew sleeps in the hulls under a tent or on deck in calm weather, much like the ancient Polynesians may have done. All the canoes can easily make five and a half knots on the wind and as much as twelve with the wind behind them. Voyaging aboard Hokule'a during an earlier inter-island trip in Hawaiian waters was like riding a rocket sled. Four of us were required to man three sweeps to keep the canoe under control!

At sea, Fleet Communications Net, VHF channel 72.

"Teo O Tonga, this is Three Daughters. I am doing 9.5 knots, with my engine going full speed and you are going faster. Slow down so that I can catch you."

With a steady beam wind, the Cook Island canoe outruns a modern motor sailor. Te'au O Tonga is sharp hulled and light. Everyone knew that she would be fast. But not this fast!

Life on Board

Saturday, April 22nd. Rizaldar proceeds north into a zone of squalls. Groggy with lack of sleep, I struggle up the companionway at midnight to relieve the watch. Ironically, because she is such a pretty yacht, many in the fleet assume Rizaldar is comfortable. They envision air conditioning, sofas in the main cabin, a television set. The reverse is true.

The Swan is all business. The cockpit holds three fifteen gallon plastic drums of diesel fuel, allowing room for only the two people on watch. There is no bimini, so we bake under the constant tropical sun. Underway, We carry only 100 gallons of water so none of it is wasted on such luxuries as bathing. After a few days at sea, my skin is rimed with an unsavory blend of salt and sweat.

During these first excruciating days before I get my sea legs, Rizaldar pitches and rolls in heavy weather. I am certain that her fury is directed at me - she wants to buck me off and throw me to the sharks. Changing the watch at night, I confront a mental image of myself bobbing helplessly in the Swan's shimmering wake.

Polaris Rising

April 24. The fleet approaches the equator with Rizaldar holding "search and rescue" position in the middle of the formation. The wind blows from the northeast at 10 to 15 knots. A blessing. If this continues we will be in Hawaiian waters in record time.

At sunset we pass a school of bottle nosed dolphins. A few hours earlier we caught a 45 pound Aku (Bonito). As we sail over the equator, we feast on Aku steaks and break out a can of cold beer for each of the crew.

As we move from the Southern Hemisphere to the Northern, Polaris rises out of the sea. The Southern Cross sinks lower. Some stars that once wheeled across the sky are now below the horizon. New ones take their place. For traditional navigators, the height of stars above the horizon at their meridian crossing (highest rising) is the key to latitude.

To help judge their height, Nainoa and his students use various pairs of stars that are a known number of degrees apart. Gacrux and Acrux, in the Southern Cross, for example, are six degrees apart. When the Southern Cross is upright (with Gacrux directly above Acrux) and the traditional navigator observes that the distance between Acrux and the horizon is the same as the distance between Acrux and Gacrux, the canoe is in the latitude of Hawaii (21 degrees north). Similarly, when the Southern Cross lies on its side Becrux is directly above Acruz. When the distance between them (four degrees) is the same as the distance between Acrux and the horizon, the canoe is at 21 degrees, 14 minutes north latitude, the same as Hawaii's South Point. Many other star pairs are used during the journey to help determine latitude in a similar way.

"This is a kind of crutch that I use," says Nainoa Thompson. "Mau is so familiar with the sky that just by looking at the dome of stars and its overall shape he knows his latitude."

Steering by the waves

April 29. Dark clouds march in from the east carrying a veil of rain beneath them. We take fresh water showers in the downbursts as the Swan buries her rail and rushes along at 9 knots. At four in the afternoon, I take the helm. With the sky completely clouded over, the canoe navigators cannot see the sun. They must be steering by the waves alone.

"One of the most difficult things to do is to learn to feel the waves," says Bruce Blankenfield, navigator of Hawai'iloa. "You always sit on the same side of the canoe when you are steering by the waves. You feel the way the canoe moves, does the bow rise first, does it fall off in a certain way, when does the second hull rise, the stern. There is a pattern to it that you have got to lock onto or you will get lost for sure."

"On the voyage between Hawaii and Tahiti, we had an entire night when we passed through squalls and we could not see the sky, so we had to steer by the waves. Before the squalls, I had a small patch of sky and a few stars near the Southern Cross that I could see so I was steering by them and I calibrated the wave patterns by them. We were steering south of east. Then the sky closed down and the wind came up so we had to brail up our sails and even so we were really moving. I steered by the waves during the night but after about eight hours the sky cleared and I could see the Southern Cross and we were still steering south of east. So I felt real good that the technique worked and I was able to use it."

Aboard Rizaldar, I decide to experiment with wave steering. First, I orient the wave train, large and steady swells moving under the boat from a little north of east. I notice that the surface of the sea is striated by the wave sets - a series of parallel diagonal lines marching to the vanishing point. I cover the compass and steer by keeping Rizaldar at a constant angle to these lines. As I focus on the far horizon, the wave train becomes a "heads up display" that allows me to engage in the larger world around me. My steering becomes more fluid and sure. Checking the compass, I find that I am invariably heading due north.

The Polynesian Renaissance

On May 6, after 17 days at sea, Rizaldar slides west in light airs under genoa and main. At 1045 the haze ahead darkens at the horizon, then hardens to reveal the shape of Hawaii's South Point. Landfall.

Behind us the canoes and their escorts are strung out in an uneven column. Te'au O Tonga is already in port, having set a record passage, but now every canoe has arrived safely after a voyage 2500 miles long and as deep as the human imagination. A gentle melancholy settles over Rizaldar's crew - an expectancy mingled with regret that this voyage, one that has tapped our emotions and physical endurance, is almost over.

Reflecting back on the trip, I remember one night in particular. As we moved through the Equatorial Counter Current, during the midnight to six watch, I experienced the arc of stars above me wheel across the sky. Some tribal people believe the stars are the spirits of their ancestors. On that night, I imagined that a pair of stars rising off the starboard bow were the spirits of my mother and father. I felt a deep welling of emotion. I imagined the milky way to be a trail of my ancestors stretching back to the original seeding of my blood line. As I looked over the side of the vessel, I saw glowing plankton turn the sea as effervescent as champagne. Large globs of green light flared up, shimmered for an instant, then slowly faded. I seemed to float through a universe of jewels, the stars above and the sea below. Here, perhaps as far away from the influence of modern life as one can get, time stood still. I imagined myself on the deck of a Polynesian canoe, making the first voyage to Hawaii. The past lived.

The renaissance of voyaging that began in Hawaii has now spread throughout Polynesia. For Rizaldar crew member Karim Cowan, a Tahitian captain, navigator and canoe builder, it has brought a profound change of course in the life of his people.

"When Captain Cook came to our islands, a European way of living and thinking replaced or Polynesian way. When I went to school, for example, the teacher used to strike me if he caught me speaking Tahitian. 'You will only speak French,' he said. Now, with the increase in voyaging, it is as if we have been given back our culture. Young teachers are teaching Tahitian in the schools. Rediscovering our voyaging has given Tahitian children something to look up to. A while ago I saw my teacher in the street and I went up to him, 'You should not have forbidden us to speak our own language,' I told him. He did not say anything. He just hung his head."

Later, at the final ceremonies celebrating the voyage, Captain Chad Baybayan of Hokule'a summed up the meaning of the voyage for Hawaiians.

"Let us not forget that it was men and women very much like us that set out on the long voyages and that from these voyages came our Polynesian culture. Our youth today sail with us, and with them we have the means to perpetuate that culture. Our horizon is bright."

THE BLESSING

By Sam Low

All of life's voyages must begin with a blessing...

Gossamer clouds slide over Kulepemoa ridge and descend into Niu valley on Oahu’s leeward coast. There is the sound of crickets and the wind and surf on a nearby beach. A few generations ago, Niu was a quiet place of chicken farms, a handful of bungalows and a dairy. Before that, Hawaii's first king, Kamehameha, often rested here from matters of state. Now it's a suburb of neat houses and trim lawns.

On March 30th, 1998, Nainoa Thompson climbs into a battered Ford station wagon, drives through the valley and takes the H1 Highway toward Honolulu. The slanting light of street lamps plays over his face, revealing strong Polynesian features. His hair is dark and curly. He is forty-three years old. When he was twenty, Nainoa began learning an arcane and almost extinct art. He studied to be ho’okele - a traditional Hawaiian navigator. He has now sailed over eighty thousand sea miles, guiding his craft from one distant island to another without instruments or charts, following a map that exists only in his mind.

Driving west on the H1, Nainoa passes streets with lyric names - Kalananaole, Wailupe, Anali'i, Laukahi. He passes small shopping malls anchored by MacDonalds and Burger Kings. Behind this man-made tangle, ridges rise up to define valleys deeply eroded by a million years of rain. Each valley was once a land division called an ahupua'a, the territory of Hawaiian noble families. Only a hundred years ago, water cascaded from the valleys’ peaks in spectacular falls, gathered in deep pools and abraded its way through lava to form streams that Hawaiian commoners channeled into their lowland taro fields. Villages dotted the coast where fish were plentiful and canoes could be easily drawn up. Now, lights can be seen in houses cantilevered over the highest ridges in a giddy display of western engineering.

As the sun rises over Waikiki’s skyscrapers, Nainoa turns off the H1 and zigzags through the industrial sprawl of the port of Honolulu. A few feet beyond a sign which says "pier 60," the battered Ford passes through a gate and parks near two large freight containers with the name "Matson" stenciled on them. Against this gritty industrial backdrop, about twenty people mill around a sailing vessel cradled in a trailer large enough to suggest that a diesel tractor would be required to pull it. The vessel gleams after eight months of refitting.

There is the murmur of conversation; the men and women gathered here know each other well. Nainoa shakes hands with each. He approaches a man taller than most - muscular but not showy, slim waisted and dark complexioned. Bruce Blankenfeld.

"Awesome job," Nainoa says.

"Thanks," Bruce says. Then he nods to the group, "it's these guys who did it."

Giving credit to others is one of Bruce’s gifts. It’s why he has only to make a call on a cell phone in his truck to find volunteers willing to drop what they’re doing and come lend a hand. Many of these volunteers know Bruce not only as boss, but as coach. During three afternoons a week, Bruce is an instructor for the Hui Nalu canoe club. His specialty is the fine points of paddling “Tahitian style” with powerful strokes that do not upset the canoe’s delicate balance and leave sensuous swirls in its wake. On a rotating schedule, often in the wee hours, Bruce earns a living by operating a huge crane to offload thirty ton containers from merchant ships docked in Honolulu.

The vessel around which they gather is the double-hulled canoe Hokule'a, a replica of ancient sailing craft that once carried Polynesian sailors on long ocean voyages. Among the people of the Polynesian Triangle Hokule’a is well known but most “mainlanders” (those who live in the continental United States) may never have heard of her. Tourists who see Hokule’a under sail reach for binoculars.

“Good God,” they say to companions, “what the hell is that?”

Their attention is attracted by the shape of Hokule’a’s twin sails which defy aerodynamic logic. The wide part is hoisted high and the sails taper toward the base of the mast - an inverted triangle. At the top, the sails belly in the wind, producing a deep concavity – the shape of a crab’s claw. Such shapes are found in petroglyphs carved into lava hundreds of years ago.

Up close, Hokule’a appears stranger still. Her twin hulls, each about sixty feet long, are joined by laminated wooden cross-beams called iakos. Hulls and iakos are united by rope lashings woven into complex patterns reminiscent of the art of M.C. Eisher. A deck is laid over the iakos to provide a place for the crew to work during the day. At night they sleep in tiny compartments inside the hulls, sometimes lulled by the slap of waves, sometimes alarmed by them. The hulls rise sharply fore and aft to terminate in a graceful arc, called a manu, adorned with wooden figures with high foreheads and protruding eyes, the akua or guardian spirits. Viewed from above, the canoe's strangeness is dispelled. She looks like a catamaran.

Hokule'a's shape is ancient but her construction is not. A hundred years ago, her sails would have been woven from Pandanus frond, but no-one knows how to do that today so they are made of canvas. Her hulls are fiberglass because no trees large enough could be found in Hawaii, and the art of carving such canoes from live wood has vanished with the ancient canoe makers, the kahuna kalai wa’a. Nainoa calls her a “performance replica.”

“We wanted to test the theory that such canoes could have carried Polynesian navigators on long voyages of exploration. We wanted to see how she sailed into the wind, off the wind, how much cargo she could carry, how she stood up to storms. Could we navigate her without instruments? Could we endure the rigors of long voyages ourselves? Frankly, that was enough of a challenge. It didn’t matter if the canoe wasn’t made of wood, as long as she performed like an ancient vessel.”

The canoe has now voyaged more than 80,000 miles throughout the Pacific. Before her refitting her hulls displayed deep gouges as if they have banged over coral reefs or been dragged up on remote Polynesian beaches. And so they had. During her long career, she has sailed to the Society Islands, the Marquesas, the Cooks, the Australs and to Samoa and New Zealand. Finally, on this last Monday in March, the work of renewing the canoe is finished.

Blessing a ship. Almost everywhere in the world ships go through a similar birthing ceremony. There are those who build her and those who sail her. Rarely are they the same people, and so in the transfer of stewardship from one group to the other, there's a pause in which the creators are recognized by the sailors; in which the builders convey the work of their hands to those who will depend upon it. Hokule’a was built in 1975 and so this particular blessing recognizes, strictly speaking, a rebirth.

Like the rituals of all nations, those practiced by Hawaiians can be elaborate, but they are often small and informal and, to the uninitiated eye, almost invisible. The priest for Hokule'a's blessing, or Kahuna as Hawaiians call such practitioners, is dressed in a tee shirt and shorts. He wears the kind of sandals you may buy in a drug store for a few dollars. He appears about forty years old. His skin is light although he is a native Hawaiian of almost pure blood. His name is Keone Nunes.

Keone was born on the island of Niihau which some consider the last stronghold of Hawaiian culture. Niihau is a privately owned place where no-one may visit without invitation. Two hundred or so native Hawaiians live there in much the same way as their ancestors have for thousands of years. The koko, or blood, of most Niihau Hawaiians is pure - a condition which is so rare that anthropologists are constantly seeking permission to study them. But none are invited to do so.

Keone begins the blessing by gathering the canoe's crew. They stand in a semi-circle, hands joined. The ceremony itself will take only about ten minutes, but without it none of the men and women who have labored over Hokule'a will feel their task is complete.

"This is a cleansing ritual," Keone tells them. "It's a ceremony to remove any bad feelings or harsh words which may linger and be a curse upon the canoe when she sets to sea. Now we will purify the canoe and join all of you in aloha."

Keone chants quietly in Hawaiian. He searches the eyes of each crew member. Then he blesses them by dipping a bundle of green tee leaves into a calabash containing salt mixed with water from a sacred spring. He makes sharp cutting movements with his bundle first to the left, then the right, then above, then below. An exorcism.

The ceremony is simple but its meaning is huge. Hokule'a has voyaged some eighty thousand miles, a statistic which encapsulates the canoe's meaning for Hawaiians but doesn’t encompass it. Also involved are thousands of hours donated by men and women laboring as shipfitters and carpenters, captains and go-fers, fundraisers and administrators – gifts of labor seemingly without end.

Keone’s simple ceremony marks the beginning of a new voyage that will take the canoe and her crew to the furthest reaches of the eastern Pacific - to one of the most difficult landfalls that can be sought by the primitive yet elegant technology of non-instrumental navigation. In a year, after extensive crew training, Hokule'a will set off for Rapa Nui - Easter Island - a tiny speck in a vast ocean.

Nainoa has planned this trip many times, both in his mind (often just before drifting off to sleep) and on a chart with a sharp pencil and a navigator’s protractor. Late one evening in February, bending over his kitchen table, he drew his course on a chart of the South Pacific Ocean. The line went southeast from Nuku Hiva in the Marquesas past the islands of Ua-po, Hiva Oa and Fatu hiva. There it turned east for about 220 miles, then southeast again 700 nautical miles to Mangareva, keeping a safe distance from the dangerously low coral atolls of the Tuamotus. From here, Nainoa laid out his course due south. It entered the horse latitudes where the canoe would experience a narrow belt of sinking air which abates the normal southeast trade winds. Continuing on to about 35 degrees south latitude, the line turns abruptly east. Here the canoe should intersect a band of prevailing westerlies and, if all goes right, she will be sailing free with the wind behind it. But things often do not go right. One textbook describes this latitude as a place where the winds are “frequently gusty and boisterous, even violent on occasion,” where they are “capricious and likely at any given moment to blow strongly from directions other than west.” This a place where fate will play a strong role. Nainoa will count on the westerlies to carry Hokule’a rapidly 500 miles to the east where he will once more change direction, this time north 300 miles to intersect the latitude of Rapa Nui.

Approaching Rapa Nui from the west, Nainoa’s course takes on a jerky zigzag motion across the last 300 miles to landfall. This is a search pattern. Rapa Nui is only 2000 feet high so a navigator, staring out from the deck of a canoe low to the ocean, cannot see the island until it is only 15 miles away. This “distance of sighting” determines the angle of each zig and zag in Nainoa’s course. If the angle is too wide, the canoe may sail past the island into the empty ocean beyond where the next landfall is Chile, 2000 miles distant. If it is too narrow, it will dangerously increase the sailing time to Rapa Nui, perhaps pushing navigator and crew beyond their limits of endurance.

Other factors are woven into the calculus of Nainoa’s course line. The optical qualities of the atmosphere, for example. If the canoe arrives in the latitude of Rapa Nui during October, as Nainoa hopes it will, he should encounter cool dry air flowing from southern polar regions. Cool air cannot carry moisture and so it is clear air which should extend Rapa Nui’s “distance of sighting.” Nainoa has also considered the phases of the moon. On October 23rd, a full moon will rise to the east of Rapa Nui, so from the deck of a canoe approaching from the west, the island will be silhouetted against the horizon.

This voyage to Rapa Nui begins as so many others - with passion and desire. For twenty-three years this has been sufficient. Somehow volunteers showed up when they were needed. Money was found. The logistics of moving relief crews across oceans and against a snarl of airline timetables were solved. Food was provided, sails were patched, broken spars repaired. But as Keone proceeds with the traditional dictates of ancient protocol a new problem looms. It is born in the success of the previous voyages, in their comprehensiveness, in the vision of Hawaiian rebirth itself. Hokule'a has brought home its message of pride. Now more Hawaiians want to participate; they want to learn the skills of their forefathers. It's also a goal of the organizers of the voyages - the Polynesian Voyaging Society. For the past two years, Hokule'a has sailed among the Hawaiian islands, from Oahu to Molokai, Molokai to Maui and so on - taking school children on their own abbreviated voyages of discovery. Wrapped around these voyages are courses in history, mathematics, astronomy. Test scores are up. Attitudes have changed. In this charged atmosphere of local achievement, some Hawaiians are questioning whether a new voyage to a distant landfall is a wise expenditure of resources. It may be difficult to raise the half million dollars needed to undertake the deep ocean passage to Rapa Nui.

Accompanied by Bruce and Nainoa, Keone ascends to Hokule'a's deck where he completes the blessing by splashing her twin hulls with the last of the water from his calabash. Then he turns to Nainoa and Bruce.

"The canoe has been purified," he says. "Do you now accept responsibility for her and for the crew who will sail aboard on the voyages to come?"

With their assent, Keone hands Nainoa and Bruce two small bundles of bananas, a symbol of Kanaloa, god of the sea, into whose keeping they are now once more committed.

Kama Hele-The Ultimate Escort Vessel

by Sam Low

Elsa and Alex Jakubenko have provided a life-time of service, protecting the crews of Hokule'a on many of her voyages. To accomplish this mission, Alex created a special vessel with his own hands...

Hokule’a's escort boat is a 45-foot steel sloop called Kama Hele-the floating home of Elsa and Alex Jakubenko. Kama Hele was built by Alex, who first began constructing sailing yachts and fishing boats in Australia in 1949. "Kama Hele" means "Traveler" as well as "A strong branch off of the trunk of a tree." The Kama Hele has accompanied Hokule’a on all of her voyages since 1992. Alex and Elsa's first encounter with The Polynesian Voyaging Society began in a roundabout way in 1972, when they moved to Taiwan to build a 65-foot ketch, Meotai. Meotai was launched in 1974 and eventually purchased from the original owner by Honolulu business man Bob Burke who would use her as Hokule’a's escort vessel on the first historic voyage to Tahiti in 1976.

When Hokule’a arrived in Tahiti, Alex and Elsa were there aboard an earlier Jakubenko built sloop called Ishka. "I saw the tremendous reception that the Tahitians gave the canoe," Alex remembers, "you would have to be there to believe it. Within twenty-four hours there were at least twenty new songs about the canoe. The voyage gave the people so much pride and excitement that both Elsa and I wanted to do something to help. But at the time, we had no idea what."

Later that year, the couple returned to Hawaii where Alex worked at Kehi Dry dock where Hokule’a was brought for overhaul after the 1976 voyage and for repair after she capsized on her 1978 trip to Tahiti. In 1980, Alex and Elsa began to escort Hokule’a with Ishka. While towing the canoe to Hilo for her departure to Tahiti, Ishka and Hokule’a were struck by a terrible storm. Even with Ishka's engines going at full speed, she could not make headway and, for a time, the two vessels were in danger of being wrecked off the Hamakua coast of the Big Island. Fortunately, good seamanship on both escort and canoe saved the day.

"If it were not for Ishka and Alex, Hokule’a might not be here today," says navigator Bruce Blankenfeld. This near disaster would provide valuable experience once Alex began to build Kama Hele.

Sailing aboard Ishka, Alex and Elsa were with Hokule’a all the way on the 1980 voyage to Tahiti and back during which Nainoa, under the watchful eyes of Mau Piailug, navigated the canoe for the first time.

During the next ten years, while other escort vessels followed in the wake of Hokule’a Alex turned his attention to building steel trawlers. But he kept thinking about his experiences and the unique needs of the escort mission. In 1991, When Nainoa asked him if he would escort Hokule’a on the voyage to Rarotonga for the Arts Festival there in 1992, Alex said yes. But he would do so with a completely new vessel, one custom built for escort duty.

In 1991, Alex laid the keel for what he hoped would be the "ultimate escort vessel" - Kama Hele. Working with a basic design by marine architect Bruce Roberts, Alex made many changes to adapt the vessel for her duties with Hokule’a. "When I thought about the design of this vessel," Alex says, "I tried to remember everything that we did right with the earlier vessels and ways to improve on our mistakes. The vessel had to meet all the requirements of escorting the canoe so that it would never fail in her mission, and that meant being able to take a tow in all kinds of weather." In addition, the escort had to be small enough so that she would not overshadow the canoe yet large enough to carry sufficient fuel for the duration of the trip.”

"She should also," Alex explained, "have plenty of room for her crew and, if necessary, for the crew of the Hokule’a. And she must be fast enough so as to never slow down the canoe."

The vessel that took shape in Alex's yard - Hawaiian Steel Boatbuilding - was a 45-foot sloop with a graceful sheer line from bow to stern. She was equipped with fuel tanks that could carry 1700 gallons of diesel, enough to allow her to steam up to 5000 miles without refueling. She is powered by a Detroit 371 diesel engine that Alex describes as "old fashioned, the kind they use in tanks or landing craft. But it will go forever and it is simple to maintain." The engine turns a propeller that is 28 inches in diameter, at least three times the normal size, one that Alex took from a 44-foot tugboat. Kama Hele carries a desalinator that is capable of producing 40 gallons of fresh water a day, more than enough for the crew of the canoe and escort combined. She is fully equipped with the latest radio and navigational gear. "The wiring was a difficult job and I needed help for that," Alex explains, "so Jerry Ongias came down and spent a lot of time making sure that everything was done just right." Also assisting Alex to meet his launch deadline were Paul Fukunaga and Jeff Merrik.

In 1992, on schedule, the new 45-foot sloop Kama Hele departed with Hokuel’a and set her course south to the Cook Islands, returning to Hawaii after a successful voyage. In 1995, Kama Hele once again headed south, this time in the company of two canoes, Hokule’a and Hawai'iloa, on yet another voyage to Tahiti where they would join up with a fleet of canoes from the Cook Islands, Aoteroa (New Zealand) and Tahiti, as well as one other canoe, Makali'i, from Hawaii. Departing Tahiti on the return trip, Kama Hele proved her mettle as a mini tug by towing two canoes simultaneously, Hawai'iloa and Te Aurere, the Måori canoe, from Tahiti to the Marquesas - all the way into strong headwinds. From the Marquesas to Hawaii, Kama Hele escorted Hawai'iloa and shortly after reaching port, she turned around and escorted the Cook Island canoe,

Takitumu back to Rarotonga.

"Elsa and Alex are at sea more than any of us," says Nainoa Thompson. "They have both proven over and over again that they are totally committed to the mission of our voyages."

"You might be able to find someone to go on escort duty who had a good boat," says Bruce Blankenfeld, "but you would not find a captain like Alex. When he says he will do something, you can be absolutely certain that it will be done."

In 1998, when Nainoa once again asked Alex and Elsa if they would agree to serve one last time, the couple could be forgiven if they had demurred. Alex and Elsa were then both in their late 70s. But, after due consideration, they agreed to take on the challenge of sailing to Rapa Nui.

"Well, you know, even at my age a person looks for a little adventure. It can get pretty boring sometimes in Honolulu," Elsa says when explaining why she decided to come on what may be the most difficult voyage of all.

“A Sea of Islands”

by Sam Low

Where land people see a barrier - island people see a road.

Seeing the Pacific as ancient Polynesians once did is a bit like the problem of perceiving solids and voids in the art of M.C. Escher. When you first look at Escher’s work you see only the solid figures in his composition. Then, blinking, the voids between the solids pop into view – a different perception of his work, crafted by the artist as a clinical psychologist might conjure optical illusions to test human perception - the perplexing difference between foreground and background.

Continental people, looking down on Hawaii from an airplane, see tiny islands in an immense ocean. When they deplane and travel around, the landscape often seems tinier still. Some visitors to Hawaii who come with plans to settle are so afflicted with this perception they get a malady called “island fever” and depart hastily. Of the total island world constructed by land and ocean, they see merely the land. But perhaps the ancient Polynesians perceived not the limits of tierra firma, not the foreground in the parlance of scholars of perception, but rather the boundless space of the ocean around them, the background. From this mental vantage point Polynesia is huge – larger than all the continents of Europe combined - and it is composed of islands joined, not separated, by ocean.

Thoughts like these have come to Nainoa Thompson unbidden during his lifetime of sailing and thinking about the process that he calls wayfinding - a concept that includes navigation but also embodies, as he once said simply, “a way of conducting yourself, a way of life.” Which is to say a way of looking at the world - what anthropologists call “culture” and philosophers call “cosmology.”

“I think that how people make a living, how they survive, and how their culture evolves are all interrelated,” Nainoa once said. “Pacific Islanders are ocean people. They know how to live and survive within the ocean environment. I think that people who for generations almost without end have evolved in an ocean world evolved a much different culture compared to people who lived in large land masses like continents.”